Amisulpride

FDA 2020, Barhemsys APPROVED, 2020/2/27

| Name |

Amisulpride (INN);

Deniban (TN); Solian (TN) アミスルプリド;

|

|---|---|

| Formula |

C17H27N3O4S

|

| CAS |

71675-85-9

|

| Mol weight |

369.479

|

Antipsychotic, Dopamine receptor antagonist, Neuropsychiatric agent

amisulpride(标准品)

Amisulpride is an antiemetic and antipsychotic medication used at lower doses intravenously to prevent and treat postoperative nausea and vomiting; and at higher doses orally and intramuscularly to treat schizophrenia and acute psychotic episodes. It is sold under the brandnames Barhemsys[6] (as an antiemetic) and Solian, Socian, Deniban and others (as an antipsychotic).[2] It is also used to treat dysthymia.[7]

It is usually classed with the atypical antipsychotics. Chemically it is a benzamide and like other benzamide antipsychotics, such as sulpiride, it is associated with a high risk of elevating blood levels of the lactation hormone, prolactin (thereby potentially causing the absence of the menstrual cycle, breast enlargement, even in males, breast milk secretion not related to breastfeeding, impaired fertility, impotence, breast pain, etc.), and a low risk, relative to the typical antipsychotics, of causing movement disorders.[8][9][10] It has also been found to be modestly more effective in treating schizophrenia than the typical antipsychotics.[9]

Amisulpride is approved for use in the United States in adults for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), either alone or in combination with an antiemetic of a different class; and to treat PONV in those who have received antiemetic prophylaxis with an agent of a different class or have not received prophylaxis.[6]

Amisulpride is believed to work by blocking, or antagonizing, the dopamine D2 receptor, reducing its signalling. The effectiveness of amisulpride in treating dysthymia and the negative symptoms of schizophrenia is believed to stem from its blockade of the presynapticdopamine D2 receptors. These presynaptic receptors regulate the release of dopamine into the synapse, so by blocking them amisulpride increases dopamine concentrations in the synapse. This increased dopamine concentration is theorized to act on dopamine D1 receptors to relieve depressive symptoms (in dysthymia) and the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.[7]

It was introduced by Sanofi-Aventis in the 1990s. Its patent expired by 2008, and generic formulations became available.[11] It is marketed in all English-speaking countries except for Canada and the United States.[10] A New York City based company, LB Pharmaceuticals, has announced the ongoing development of LB-102, also known as N-methyl amisulpride, an antipsychotic specifically targeting the United States.[12][13] A poster presentation at European Neuropsychopharmacology[14] seems to suggest that this version of amisulpride, known as LB-102 displays the same binding to D2, D3 and 5HT7 that amisulpride does.[15][16]

Medical uses

Schizophrenia

In a 2013 study in a comparison of 15 antipsychotic drugs in effectiveness in treating schizophrenic symptoms, amisulpride was ranked second and demonstrated high effectiveness. 11% more effective than olanzapine (3rd), 32-35% more effective than haloperidol, quetiapine, and aripiprazole, and 25% less effective than clozapine (1st).[9] Although according to other studies it appears to have comparable efficacy to olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia.[17][18] Amisulpride augmentation, similarly to sulpirideaugmentation, has been considered a viable treatment option (although this is based on low-quality evidence) in clozapine-resistant cases of schizophrenia.[19][20] Another recent study concluded that amisulpride is an appropriate first-line treatment for the management of acute psychosis.[21]

Contraindications

Amisulpride’s use is contraindicated in the following disease states[2][22][8]

- Pheochromocytoma

- Concomitant prolactin-dependent tumours e.g. prolactinoma, breast cancer

- Movement disorders (e.g. Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies)

- Lactation

- Children before the onset of puberty

Neither is it recommended to use amisulpride in patients with hypersensitivities to amisulpride or the excipients found in its dosage form.[2]

Adverse effects

- Very Common (≥10% incidence)[1]

- Extrapyramidal side effects (EPS; including dystonia, tremor, akathisia, parkinsonism). Produces a moderate degree of EPS; more than aripiprazole (not significantly, however), clozapine, iloperidone (not significantly), olanzapine (not significantly), quetiapine (not significantly) and sertindole; less than chlorpromazine (not significantly), haloperidol, lurasidone (not significantly), paliperidone (not significantly), risperidone (not significantly), ziprasidone (not significantly) and zotepine (not significantly).[9]

- Insomnia

- Hypersalivation

- Nausea

- Headache

- Hyperactivity

- Anxiety

- Vomiting

- Hyperprolactinaemia (which can lead to galactorrhoea, breast enlargement and tenderness, sexual dysfunction, etc.)

- Weight gain (produces less weight gain than chlorpromazine, clozapine, iloperidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, zotepine and more (although not statistically significantly) weight gain than haloperidol, lurasidone, ziprasidone and approximately as much weight gain as aripiprazole and asenapine)[9]

- Anticholinergic side effects (although it does not bind to the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and hence these side effects are usually quite mild) such as

- – constipation

- – dry mouth

- – disorder of accommodation

- – Blurred vision

- Rare (<1% incidence)[1][2][23][22][8]

- Blood dyscrasias such as leucopenia, neutropenia and agranulocytosis

- QT interval prolongation (in a recent meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of 15 antipsychotic drugs amisulpride was found to have the 2nd highest effect size for causing QT interval prolongation[9])

Hyperprolactinaemia results from antagonism of the D2 receptors located on the lactotrophic cells found in the anterior pituitary gland. Amisulpride has a high propensity for elevating plasma prolactin levels as a result of its poor blood-brain barrier penetrability and hence the resulting greater ratio of peripheral D2 occupancy to central D2 occupancy. This means that to achieve the sufficient occupancy (~60–80%[24]) of the central D2 receptors in order to elicit its therapeutic effects a dose must be given that is enough to saturate peripheral D2receptors including those in the anterior pituitary.[25][26]

- Somnolence. It produces minimal sedation due to its absence of cholinergic, histaminergic and alpha adrenergic receptor antagonism. It is one of the least sedating antipsychotics.[9]

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotics to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[27] Symptoms of withdrawal commonly include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.[28] Other symptoms may include restlessness, increased sweating, and trouble sleeping.[28] Less commonly there may be a felling of the world spinning, numbness, or muscle pains.[28] Symptoms generally resolve after a short period of time.[28]

There is tentative evidence that discontinuation of antipsychotics can result in psychosis.[29] It may also result in reoccurrence of the condition that is being treated.[30] Rarely tardive dyskinesia can occur when the medication is stopped.[28]

Overdose

Torsades de pointes is common in overdose.[31][32] Amisulpride is moderately dangerous in overdose (with the TCAs being very dangerous and the SSRIs being modestly dangerous).[33][34]

Interactions

Amisulpride should not be used in conjunction with drugs that prolong the QT interval (such as citalopram, venlafaxine, bupropion, clozapine, tricyclic antidepressants, sertindole, ziprasidone, etc.),[33] reduce heart rate and those that can induce hypokalaemia. Likewise it is imprudent to combine antipsychotics due to the additive risk for tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[33]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Amisulpride and its relatives sulpiride, levosulpiride, and sultopride have been shown to bind to the high-affinity GHB receptor at concentrations that are therapeutically relevant (IC50 = 50 nM for amisulpride).[37]Amisulpride functions primarily as a dopamine D2 and D3 receptor antagonist. It has high affinity for these receptors with dissociation constantsof 3.0 and 3.5 nM, respectively.[36] Although standard doses used to treat psychosis inhibit dopaminergic neurotransmission, low doses preferentially block inhibitory presynaptic autoreceptors. This results in a facilitation of dopamine activity, and for this reason, low-dose amisulpride has also been used to treat dysthymia.[2]

Amisulpride, sultopride and sulpiride respectively present decreasing in vitro affinities for the D2 receptor (IC50 = 27, 120 and 181 nM) and the D3 receptor (IC50 = 3.6, 4.8 and 17.5 nM).[39]

Though it was long widely assumed that dopaminergic modulation is solely responsible for the respective antidepressant and antipsychoticproperties of amisulpride, it was subsequently found that the drug also acts as a potent antagonist of the serotonin 5-HT7 receptor (Ki = 11.5 nM).[36] Several of the other atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone and ziprasidone are potent antagonists at the 5-HT7 receptor as well, and selective antagonists of the receptor show antidepressant properties themselves. To characterize the role of the 5-HT7 receptor in the antidepressant effects of amisulpride, a study prepared 5-HT7 receptor knockout mice.[36] The study found that in two widely used rodent models of depression, the tail suspension test, and the forced swim test, those mice did not exhibit an antidepressant response upon treatment with amisulpride.[36] These results suggest that 5-HT7 receptor antagonism mediates the antidepressant effects of amisulpride.[36]

Amisulpride also appears to bind with high affinity to the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor (Ki = 13 nM), where it acts as an antagonist.[36] The clinical implications of this, if any, are unclear.[36] In any case, there is no evidence that this action mediates any of the therapeutic effects of amisulpride.[36]

Society and culture

Brand names

Brand names include: Amazeo, Amipride (AU), Amival, Solian (AU, IE, RU, UK, ZA), Soltus, Sulpitac (IN), Sulprix (AU), Midora (RO) and Socian (BR).[40][41]

Availability

Amisulpride was not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States until February 2020, but it is used in Europe,[41]Israel, Mexico, India, New Zealand and Australia[2] to treat psychosis and schizophrenia.[42][43]

Amisulpride was approved for use in the United States in February 2020.[44][6]

CLIP

Dopamine receptor antagonist. Prepn: M. Thominet et al., BE 872585; eidem, U.S. Patent 4,401,822 (1979, 1983 both to Soc. d’Etudes Sci. Ind. de l’Ile-de-France).

CLIP

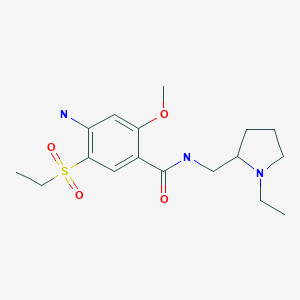

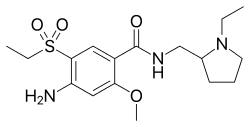

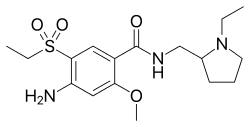

4-Amino-N-((1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)methyl)-5-(ethylsulfonyl)-o-anisamide, could be produced through many synthetic methods.

Following is one of the synthesis routes:

Firstly, the acetylation of 5-aminosalicylic acid (I) with acetic anhydride in hot acetic acid affords 5-acetaminosalicylic acid (II), which is methylated with dimethyl sulfate and K2CO3 in refluxing acetone producing methyl 2-methoxy-5-acetaminobenzoate (III). Secondly, nitration of (III) with HNO3 in acetic acid affords methyl 2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-acetaminobenzoate (IV), which is deacetylated with H2SO4 in refluxing methanol to give methyl 2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-aminobenzoate (V). Next, the diazotation of (V) with NaNO2-HCl, followed by reaction with sodium ethylmercaptide, oxidation with H2O2 and hydrolysis with NaOH in ethanol yields 2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-(ethylsulfonyl)benzoic acid (VI), which is condensed with N-ethyl-2-aminomethylpyrrolidine (VII) in the presence of ethyl chloroformate and triethylamine in dioxane affording 2-methoxy-4-nitro-N-[(1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinyl) methyl]-5-(ethylsulfonyl)benzamide (VIII). At last, this compound is reduced with H2 over Raney-Ni in ethanol.

CLIP

BE 0872585; ES 476755; FR 2415099; GB 2083458; JP 54145658; US 4294828; US 4401822

Alkylation of 2-methoxy-4-amino-5-mercaptobenzoic acid (X) with diethyl sulfate acid Na2CO3 gives 2-methoxy-4-amino-5-ethylthiobenzoic acid (XI), which is oxidized with H2O2 in acetic acid yielding 2-methoxy-4-amino-5-(ethylsulfonyl)benzoic acid (XII). Finally, this compound is condensed with (VII) by means of ethyl chloroformate.

CLIP

| FR 2460930 |

Acetylation of 5-aminosalicylic acid (I) with acetic anhydride in hot acetic acid gives 5-acetaminosalicylic acid (II), which is methylated with dimethyl sulfate and K2CO3 in refluxing acetone yielding methyl 2-methoxy-5-acetaminobenzoate (III). Nitration of (III) with HNO3 in acetic acid affords methyl 2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-acetaminobenzoate (IV), which is deacetylated with H2SO4 in refluxing methanol to give methyl 2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-aminobenzoate (V). The diazotation of (V) with NaNO2-HCl, followed by reaction with sodium ethylmercaptide, oxidation with H2O2 and hydrolysis with NaOH in ethanol yields 2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-(ethylsulfonyl)benzoic acid (VI), which is condensed with N-ethyl-2-aminomethylpyrrolidine (VII) by means of ethyl chloroformate and triethylamine in dioxane affording 2-methoxy-4-nitro-N-[(1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinyl) methyl]-5-(ethylsulfonyl)benzamide (VIII). Finally, this compound is reduced with H2 over Raney-Ni in ethanol.

CLIP

Treatment of thiourea (I) with iodomethane provided S-methylthiouronium iodide (II). This was further condensed with N-methylpiperazine (III) to afford the intermediate piperazine-1-carboxamidine (IV)

CLIP

Regioselective lithiation of 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene (V) with n-BuLi at -60 C, followed by quenching of the resultant organolithium compound (VI) with N,N-dimethylformamide yielded 2,3,5-trichlorobenzaldehyde (VII) (1), which was then reduced with NaBH4 to provide alcohol (VIII). Bromination of (VIII) using PBr3 afforded compound (IX), whose bromide atom was displaced with KCN to give the trichlorophenylacetonitrile (X). Claisen condensation of (X) with ethyl formate in the presence of NaOEt furnished the oxo nitrile sodium enolate (XI), which was subsequently O-alkylated with iodomethane yielding the methoxy acrylonitrile (XII). Finally, cyclization of (XII) with the piperazine-1-carboxamidine (IV) in EtOH gave rise to the target pyrimidine derivative

PATENT

https://patents.google.com/patent/US20130096319A1/en

Amisulpride is represented by the formula (I) as given below.

The product patent U.S. Pat. No. 4,401,822 describes preparation of amisulpride as shown in scheme (I)

The synthesis of amisulpride involves oxidation of 2-methoxy-4-amino-5-ethyl-thio benzoic acid (III) using acetic acid and hydrogen peroxide at 40-45° C. for few hours to obtain 2-methoxy-4-amino-5-ethyl-sulfonyl benzoic acid (IV). In our attempt to repeat this reaction, we found that almost 22 hours were required for completion and the purity of compound (IV) was 87.6%.

- [0006]

Thus, the product patent method suffers from the disadvantages such as high reaction time, low yield and low purity.

- [0007]

Liu Lie et al, Jingxi Huagong Zhongjianti 2008, 38 (3), 29-32 describes the process for the preparation of 2-methoxy-4-amino-5-ethyl-sulfonyl benzoic acid (IV) as shown in scheme (II).

- [0008]

4-amino salicylic acid (VI) is treated with dimethyl sulphate in the presence of potassium hydroxide and acetone to give 4-amino-2-methoxy-methyl benzoate in 4 hours, which is further treated with potassium thiocynate to give compound of formula (VIII). 4-Amino-2-,methoxy-5-thiocyanatobenzoate (VIII) is treated with bromoethane to give 4-amino-5-ethylthio-2-methoxy benzoic acid (IX) which is further converted to 2-methoxy-4-amino-5-ethyl-sulfonyl benzoic acid (IV) via oxidation with hydrogen peroxide and acetic acid.

- [0009]

The yield of conversion of compound (VIII) to compound (IX) is 57% and the overall yield of compound (IV) from compound (VI) is 24% only. Thus, the above process suffers from the disadvantages such as low yield and in that it uses bromoethane which is skin and eye irritant and has carcinogenic effects.

- [0010]

Therefore, there is, an unfulfilled need to provide industrially feasible process for the preparation of 2-methoxy-4-amino-5-ethyl-sulfonyl benzoic acid (IV) and amisulpride (I) with higher purity and yield, since it is one of the key intermediates in the manufacture of amisulpride.

SUMMARY OF THE INVENTION

- [0097]

Preparation of crude amisulpride

- [0098]

To a stirring mixture of 4-amino-2-methoxy-5-ethyl sulphonyl benzoic acid (IV) and acetone (5.0 L) at 0-5° C., triethyl amine (0.405 Kg) was added and stirred followed by addition of ethyl chloroformate (0.368 Kg). N-ethyl-2-amino methyl pyrrolidine (0.627 Kg) was added to the reaction mass at 5-10° C. Temperature of reaction mass was raised to 25-30° C. and stirred for 120 min. To the same reaction mass triethyl amine (0.405 Kg) and ethyl chloroformate (0.368 Kg) was added with maintaining the temperature. Reaction mass was stirred for 120 min. After completion of reaction, water (4.0 L) was added. Reaction mass was filtered and washed with water (2.0 L). Filtrate was collected and water was added (9.0 L). pH of the reaction mass was adjusted to 10.8-11.2 by using 20% NaOH solution. Reaction mass was stirred for 240-300 min, filtered and washed with water. Solid was dried under vacuum

- [0099]

Yield : 70%

- [0100]

Purity: 98%

- Example 13

Example 14

- [0101]

Purification of amisulpride

- [0102]

Amisulpride (1 kg) was charged in acetone (6 liters) and the reaction mixture was heated till a clear solution was obtained. Slurry of activated carbon (0.1 kg in 1 liter) was added in acetone. The reaction mass was stirred at 50-55 ° C. for 60 minutes and filtered hot. The filtrate was concentrated and further heated to dissolve the solid. The reaction mass was cooled to 0-5° C., stirred and filtered. The precipitated solid was washed with acetone and dried.

- [0103]

Yield: 750 gm (75%)

- [0104]

HPLC purity: 99.8% (quantitative)

- [0105]

M.P.: 125° C.

- [0106]

DSC: shows endotherm at 133° C.

- [0107]

Particle size: d10=0.637, d50=6.0, d90=13.325 microns

CLIP

https://watermark.silverchair.com/bmw186.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAmEwggJdBgkqhkiG9w0BBwagggJOMIICSgIBADCCAkMGCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQM_rfBl_qrJE7Y7K67AgEQgIICFOQ9ug62uUxOD4oCuuUGlGD3N04qUgCHew1O5UIyknvohf-_QUaJclqSZM6k5UhPTLgjkYyVMVgS04HMcDKUVXr1cMUfV6cExwayFb8z3MQUF4Ny6s8hPuAMJO4XsTm4qh0nnEykHwgMonNWdDr32D4B7NuEVwGE_5Z-d1yQvAdkNeCmEbHIaue3OTiocWodCsAv8yUdnXf1AtreXJkvsiAQtk4oCddsM_a2njiXJAc-VcFgTImCvsaCY-_eWT91Dc3gb7fpEAJSPLl06xx30GziAvF_hl5P33TaMFmVm_p-0rJGWi-_x92Tlo1CkuR1N1oWlcnuBSPqKeX3tbMO3phnIYtbDPycftd6UKI2f9-zyMRHgSId4xJCpaxvy6fndrWZ1qrHTyQLt_XqncL7zD8aYHER67kV3g30ZgAtcivHoMSHj9h4wGD5WLZ5-M4cZ0dpUyKx3E2njYBEBe0LNQyqDmP8HKpM_RBN2C2nuD2h1fJkiwf2kLAdlBC6gOhjl60XqU_7ARJZf_86kR3OhUJ5f8Ey2R-k3zwDHEc3tU10AlEky9ne-UWVHGjOCd9L-SV-eXfjOnaERGw9EHahxajGBCRuqa07-BtbV0mr53AKyaS5YUTQ2EZ7P3WarhImsJpYiQxWAuSlYn2F11RTMu_KjP7-DMXbX6pcq20axI2NNwrBtfsDXFbQWZ8q9R0FYGsUS90

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Amisulpride 100 mg Tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)”. (emc). 5 July 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k “Solian tablets and solution product information” (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 26 February2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Rosenzweig, P.; Canal, M.; Patat, A.; Bergougnan, L.; Zieleniuk, I.; Bianchetti, G. (2002). “A review of the pharmacokinetics, tolerability and pharmacodynamics of amisulpride in healthy volunteers”. Human Psychopharmacology. 17 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1002/hup.320. PMID 12404702.

- ^ Caccia, S (May 2000). “Biotransformation of Post-Clozapine Antipsychotics Pharmacological Implications”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 38 (5): 393–414. doi:10.2165/00003088-200038050-00002. PMID 10843459.

- ^ Noble, S; Benfield, P (December 1999). “Amisulpride: A Review of its Clinical Potential in Dysthymia”. CNS Drugs. 12 (6): 471–483. doi:10.2165/00023210-199912060-00005.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Barhemsys (amisulpride) injection, for intravenous use” (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Pani L, Gessa GL (2002). “The substituted benzamides and their clinical potential on dysthymia and on the negative symptoms of schizophrenia”. Molecular Psychiatry. 7 (3): 247–53. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001040. PMID 11920152.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Leucht, S; Cipriani, A; Spineli, L; Mavridis, D; Orey, D; Richter, F; Samara, M; Barbui, C; Engel, RR; Geddes, JR; Kissling, W; Stapf, MP; Lässig, B; Salanti, G; Davis, JM (September 2013). “Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis”. Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Brayfield, A, ed. (June 2017). “Amisulpride: Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference”. MedicineComplete. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ De Silva, V; Hanwella, R (April 2008). “Pharmaceutical patents and the quality of mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries”. The Psychiatrist. 32 (4): 121–23. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.107.015651.

- ^ “Pipeline”. LB Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ “About Us”. LB Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ “Data presented at 2017 ECNP meeting (European Neuropsychopharmacology, 2017, 27 (S4), S922-S923)”. LB Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ “Building a translational bridge from animals to man for clinical candidate LB-102, a next-generation benzamide antipsychotic (P.101)” (PDF). LB Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Grattan V, Vaino AR, Prensky Z, Hixon MS (August 2019). “Antipsychotic Benzamides Amisulpride and LB-102 Display Polypharmacy as Racemates, S Enantiomers Engage Receptors D2 and D3, while R Enantiomers Engage 5-HT7”. ACS Omega. 4 (9): 14151–4. doi:10.1021/acsomega.9b02144. ISSN 2470-1343. PMC 6714530. PMID 31497735.

- ^ Komossa, K; Rummel-Kluge, C; Hunger, H; Schmid, F; Schwarz, S; Silveira da Mota Neto, JI; Kissling, W; Leucht, S (January 2010). “Amisulpride versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia”. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD006624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006624.pub2. PMC 4164462. PMID 20091599.

- ^ Leucht, S; Corves, C; Arbter, D; Engel, RR; Li, C; Davis, JM (January 2009). “Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis”. Lancet. 373 (9657): 31–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. PMID 19058842.

- ^ Solanki, RK; Sing, P; Munshi, D (October–December 2009). “Current perspectives in the treatment of resistant schizophrenia”. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 51 (4): 254–60. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.58289. PMC 2802371. PMID 20048449.

- ^ Mouaffak, F; Tranulis, C; Gourevitch, R; Poirier, MF; Douki, S; Olié, JP; Lôo, H; Gourion, D (2006). “Augmentation Strategies of Clozapine With Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Ultraresistant Schizophrenia”. Clinical Neuropharmacology. 29 (1): 28–33. doi:10.1097/00002826-200601000-00009. PMID 16518132.

- ^ Nuss, P.; Hummer, M.; Tessier, C. (2007). “The use of amisulpride in the treatment of acute psychosis”. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 3 (1): 3–11. doi:10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.1.3. PMC 1936283. PMID 18360610.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DRUGDEX System (Internet) [cited 2013 Sep 19]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- ^ Brunton, L; Chabner, B; Knollman, B (2010). Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ McKeage, K; Plosker, GL (2004). “Amisulpride: a review of its use in the management of schizophrenia”. CNS Drugs. 18 (13): 933–956. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418130-00007. ISSN 1172-7047. PMID 15521794.

- ^ Natesan, S; Reckless, GE; Barlow, KB; Nobrega, JN; Kapur, S (October 2008). “Amisulpride the ‘atypical’ atypical antipsychotic — Comparison to haloperidol, risperidone and clozapine”. Schizophrenia Research. 105 (1–3): 224–235. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.005. PMID 18710798.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). “4.2.1”. British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Haddad, Peter; Haddad, Peter M.; Dursun, Serdar; Deakin, Bill (2004). Adverse Syndromes and Psychiatric Drugs: A Clinical Guide. OUP Oxford. p. 207–216. ISBN 9780198527480.

- ^ Moncrieff J (July 2006). “Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse”. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655.

- ^ Sacchetti, Emilio; Vita, Antonio; Siracusano, Alberto; Fleischhacker, Wolfgang (2013). Adherence to Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 85. ISBN 9788847026797.

- ^ Isbister, GK; Balit, CR; Macleod, D; Duffull, SB (August 2010). “Amisulpride overdose is frequently associated with QT prolongation and torsades de pointes”. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 30 (4): 391–395. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181e5c14c. PMID 20531221.

- ^ Joy, JP; Coulter, CV; Duffull, SB; Isbister, GK (August 2011). “Prediction of Torsade de Pointes From the QT Interval: Analysis of a Case Series of Amisulpride Overdoses”. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 90 (2): 243–245. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.107. PMID 21716272.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Taylor, D; Paton, C; Shitij, K (2012). Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry(11th ed.). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-47-097948-8.

- ^ Levine, M; Ruha, AM (July 2012). “Overdose of atypical antipsychotics: clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity and management”. CNS Drugs. 26 (7): 601–611. doi:10.2165/11631640-000000000-00000. PMID 22668123.

- ^ Roth, BL; Driscol, J. “PDSP Ki Database”. Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar asat au av aw Abbas AI, Hedlund PB, Huang XP, Tran TB, Meltzer HY, Roth BL (2009). “Amisulpride is a potent 5-HT7 antagonist: relevance for antidepressant actions in vivo”. Psychopharmacology. 205 (1): 119–28. doi:10.1007/s00213-009-1521-8. PMC 2821721. PMID 19337725.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Maitre, M.; Ratomponirina, C.; Gobaille, S.; Hodé, Y.; Hechler, V. (April 1994). “Displacement of [3H] gamma-hydroxybutyrate binding by benzamide neuroleptics and prochlorperazine but not by other antipsychotics”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 256(2): 211–214. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(94)90248-8. PMID 7914168.

- ^ Schoemaker H, Claustre Y, Fage D, Rouquier L, Chergui K, Curet O, Oblin A, Gonon F, Carter C, Benavides J, Scatton B (1997). “Neurochemical characteristics of amisulpride, an atypical dopamine D2/D3 receptor antagonist with both presynaptic and limbic selectivity”. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 280 (1): 83–97. PMID 8996185.

- ^ Blomme, Audrey; Conraux, Laurence; Poirier, Philippe; Olivier, Anne; Koenig, Jean-Jacques; Sevrin, Mireille; Durant, François; George, Pascal (2000), “Amisulpride, Sultopride and Sulpiride: Comparison of Conformational and Physico-Chemical Properties”, Molecular Modeling and Prediction of Bioactivity, Springer US, pp. 404–405, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4141-7_97, ISBN 9781461368571

- ^ “Amisulpride international”. Drugs.com. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Active substance: amisulpride” (PDF). 28 September 2017. EMA/658194/2017; Procedure no.: PSUSA/00000167/201701. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Lecrubier, Y.; et al. (2001). “Consensus on the Practical Use of Amisulpride, an Atypical Antipsychotic, in the Treatment of Schizophrenia”. Neuropsychobiology. 44 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1159/000054913. PMID 11408792.

- ^ Kaplan, A. (2004). “Psychotropic Medications Around the World”. Psychiatric Times. 21(5).

- ^ “Barhemsys: FDA-Approved Drugs”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 26 February 2020.

External links

- “Amisulpride”. Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Clinical trial number NCT01991860 at ClinicalTrials.gov

- Clinical trial number NCT02337062 at ClinicalTrials.gov

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Solian, Barhemsys, others |

| Other names | APD421 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 48%[3][2] |

| Protein binding | 16%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (minimal; most excreted unchanged)[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 12 hours[3] |

| Excretion | Renal[3] (23–46%),[4][5]Faecal[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.068.916 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H27N3O4S |

| Molar mass | 369.48 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

- Rosenzweig P, Canal M, Patat A, Bergougnan L, Zieleniuk I, Bianchetti G: A review of the pharmacokinetics, tolerability and pharmacodynamics of amisulpride in healthy volunteers. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002 Jan;17(1):1-13. [PubMed:12404702]

- Moller HJ: Amisulpride: limbic specificity and the mechanism of antipsychotic atypicality. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003 Oct;27(7):1101-11. [PubMed:14642970]

- Weizman T, Pick CG, Backer MM, Rigai T, Bloch M, Schreiber S: The antinociceptive effect of amisulpride in mice is mediated through opioid mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003 Oct 8;478(2-3):155-9. [PubMed:14575800]

- Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Engel RR, Kissling W: Amisulpride, an unusual “atypical” antipsychotic: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 Feb;159(2):180-90. [PubMed:11823257]

- Rehni AK, Singh TG, Chand P: Amisulpride-induced seizurogenic effect: a potential role of opioid receptor-linked transduction systems. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011 May;108(5):310-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2010.00655.x. Epub 2010 Dec 22. [PubMed:21176108]

Patent

Non-Patent

///////////////Amisulpride, アミスルプリド , 标准品 , FDA 2020, 2020 APPROVALS, Barhemsys, SOLIAN, Antipsychotic, Benzamides, Dopamine Receptor Antagonist,

CCN1CCCC1CNC(=O)C1=CC(=C(N)C=C1OC)S(=O)(=O)CC