Brexanolone

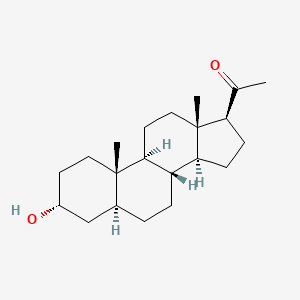

318.501 g/mol, C21H34O2

CAS: 516-54-1

ブレキサノロン

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved Zulresso (brexanolone) injection for intravenous (IV) use for the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD) in adult women. This is the first drug approved by the FDA specifically for PPD.

March 19, 2019

Release

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved Zulresso (brexanolone) injection for intravenous (IV) use for the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD) in adult women. This is the first drug approved by the FDA specifically for PPD.

“Postpartum depression is a serious condition that, when severe, can be life-threatening. Women may experience thoughts about harming themselves or harming their child. Postpartum depression can also interfere with the maternal-infant bond. This approval marks the first time a drug has been specifically approved to treat postpartum depression, providing an important new treatment option,” said Tiffany Farchione, M.D., acting director of the Division of Psychiatry Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Because of concerns about serious risks, including excessive sedation or sudden loss of consciousness during administration, Zulresso has been approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) and is only available to patients through a restricted distribution program at certified health care facilities where the health care provider can carefully monitor the patient.”

PPD is a major depressive episode that occurs following childbirth, although symptoms can start during pregnancy. As with other forms of depression, it is characterized by sadness and/or loss of interest in activities that one used to enjoy and a decreased ability to feel pleasure (anhedonia) and may present with symptoms such as cognitive impairment, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, or suicidal ideation.

Zulresso will be available only through a restricted program called the Zulresso REMS Program that requires the drug be administered by a health care provider in a certified health care facility. The REMS requires that patients be enrolled in the program prior to administration of the drug. Zulresso is administered as a continuous IV infusion over a total of 60 hours (2.5 days). Because of the risk of serious harm due to the sudden loss of consciousness, patients must be monitored for excessive sedation and sudden loss of consciousness and have continuous pulse oximetry monitoring (monitors oxygen levels in the blood). While receiving the infusion, patients must be accompanied during interactions with their child(ren). The need for these steps is addressed in a Boxed Warning in the drug’s prescribing information. Patients will be counseled on the risks of Zulresso treatment and instructed that they must be monitored for these effects at a health care facility for the entire 60 hours of infusion. Patients should not drive, operate machinery, or do other dangerous activities until feelings of sleepiness from the treatment have completely gone away.

The efficacy of Zulresso was shown in two clinical studies in participants who received a 60-hour continuous intravenous infusion of Zulresso or placebo and were then followed for four weeks. One study included patients with severe PPD and the other included patients with moderate PPD. The primary measure in the study was the mean change from baseline in depressive symptoms as measured by a depression rating scale. In both placebo controlled studies, Zulresso demonstrated superiority to placebo in improvement of depressive symptoms at the end of the first infusion. The improvement in depression was also observed at the end of the 30-day follow-up period.

The most common adverse reactions reported by patients treated with Zulresso in clinical trials include sleepiness, dry mouth, loss of consciousness and flushing. Health care providers should consider changing the therapeutic regimen, including discontinuing Zulresso in patients whose PPD becomes worse or who experience emergent suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

The FDA granted this application Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapydesignation.

Approval of Zulresso was granted to Sage Therapeutics, Inc.

Allopregnanolone, also known as 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one or 3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone (3α,5α-THP), as well as brexanolone (USAN),[1] is an endogenous inhibitory pregnane neurosteroid[2] which has been approved by the FDA as a treatment for post-partum depression. It is synthesized from progesterone, and is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the action of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at GABAA receptor.[2] Allopregnanolone has effects similar to those of other positive allosteric modulators of the GABA action at GABAA receptor such as the benzodiazepines, including anxiolytic, sedative, and anticonvulsant activity.[2][3][4] Endogenously produced allopregnanolone exerts a pivotal neurophysiological role by fine-tuning of GABAA receptor and modulating the action of several positive allosteric modulators and agonists at GABAA receptor.[5] The 21-hydroxylated derivative of this compound, tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC), is an endogenous inhibitory neurosteroid with similar properties to those of allopregnanolone, and the 3β-methyl analogue of allopregnanolone, ganaxolone, is under development to treat epilepsy and other conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[2]

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of allopregnanolone in the brain starts with the conversion of progesterone into 5α-dihydroprogesterone by 5α-reductase type I. After that, 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase converts this intermediate into allopregnanolone.[2] Allopregnanolone in the brain is produced by cortical and hippocampus pyramidal neurons and pyramidal-like neurons of the basolateral amygdala.[6]

Biological activity

Allopregnanolone acts as a highly potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor.[2] While allopregnanolone, like other inhibitory neurosteroids such as THDOC, positively modulates all GABAA receptor isoforms, those isoforms containing δ subunitsexhibit the greatest potentiation.[7] Allopregnanolone has also been found to act as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA-ρ receptor, though the implications of this action are unclear.[8][9] In addition to its actions on GABA receptors, allopregnanolone, like progesterone, is known to be a negative allosteric modulator of nACh receptors,[10] and also appears to act as a negative allosteric modulator of the 5-HT3 receptor.[11] Along with the other inhibitory neurosteroids, allopregnanolone appears to have little or no action at other ligand-gated ion channels, including the NMDA, AMPA, kainate, and glycine receptors.[12]

Unlike progesterone, allopregnanolone is inactive at the nuclear progesterone receptor (nPR).[12] However, allopregnanolone can be intracellularly oxidized into 5α-dihydroprogesterone, which is an agonist of the nPR, and thus/in accordance, allopregnanolone does appear to have indirect nPR-mediated progestogenic effects.[13] In addition, allopregnanolone has recently been found to be an agonist of the newly discovered membrane progesterone receptors (mPR), including mPRδ, mPRα, and mPRβ, with its activity at these receptors about a magnitude more potent than at the GABAA receptor.[14][15] The action of allopregnanolone at these receptors may be related, in part, to its neuroprotective and antigonadotropic properties.[14][16] Also like progesterone, recent evidence has shown that allopregnanolone is an activator of the pregnane X receptor.[12][17]

Similarly to many other GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators, allopregnanolone has been found to act as an inhibitor of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (L-VGCCs),[18] including α1 subtypes Cav1.2 and Cav1.3.[19] However, the threshold concentration of allopregnanolone to inhibit L-VGCCs was determined to be 3 μM (3,000 nM), which is far greater than the concentration of 5 nM that has been estimated to be naturally produced in the human brain.[19] Thus, inhibition of L-VGCCs is unlikely of any actual significance in the effects of endogenous allopregnanolone.[19] Also, allopregnanolone, along with several other neurosteroids, has been found to activate the G protein-coupled bile acid receptor (GPBAR1, or TGR5).[20] However, it is only able to do so at micromolar concentrations, which, similarly to the case of the L-VGCCs, are far greater than the low nanomolar concentrations of allopregnanolone estimated to be present in the brain.[20]

Biological function

Allopregnanolone possesses a wide variety of effects, including, in no particular order, antidepressant, anxiolytic, stress-reducing, rewarding,[21] prosocial,[22] antiaggressive,[23]prosexual,[22] sedative, pro-sleep,[24] cognitive, memory-impairment, analgesic,[25] anesthetic, anticonvulsant, neuroprotective, and neurogenic effects.[2] Fluctuations in the levels of allopregnanolone and the other neurosteroids seem to play an important role in the pathophysiology of mood, anxiety, premenstrual syndrome, catamenial epilepsy, and various other neuropsychiatric conditions.[26][27][28]

Increased levels of allopregnanolone can produce paradoxical effects, including negative mood, anxiety, irritability, and aggression.[29][30][31] This appears to be because allopregnanolone possesses biphasic, U-shaped actions at the GABAA receptor – moderate level increases (in the range of 1.5–2 nM/L total allopregnanolone, which are approximately equivalent to luteal phase levels) inhibit the activity of the receptor, while lower and higher concentration increases stimulate it.[29][30] This seems to be a common effect of many GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators.[26][31] In accordance, acute administration of low doses of micronized progesterone (which reliably elevates allopregnanolone levels) has been found to have negative effects on mood, while higher doses have a neutral effect.[32]

During pregnancy, allopregnanolone and pregnanolone are involved in sedation and anesthesia of the fetus.[33][34]

Chemistry

Allopregnanolone is a pregnane (C21) steroid and is also known as 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one, 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one, or 3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone (3α,5α-THP). It is very closely related structurally to 5-pregnenolone (pregn-5-en-3β-ol-20-dione), progesterone (pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione), the isomers of pregnanedione (5-dihydroprogesterone; 5-pregnane-3,20-dione), the isomers of 4-pregnenolone (3-dihydroprogesterone; pregn-4-en-3-ol-20-one), and the isomers of pregnanediol (5-pregnane-3,20-diol). In addition, allopregnanolone is one of four isomers of pregnanolone (3,5-tetrahydroprogesterone), with the other three isomers being pregnanolone (5β-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one), isopregnanolone(5α-pregnan-3β-ol-20-one), and epipregnanolone (5β-pregnan-3β-ol-20-one).

Derivatives

A variety of synthetic derivatives and analogues of allopregnanolone with similar activity and effects exist, including alfadolone (3α,21-dihydroxy-5α-pregnane-11,20-dione), alfaxolone (3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnane-11,20-dione), ganaxolone (3α-hydroxy-3β-methyl-5α-pregnan-20-one), hydroxydione (21-hydroxy-5β-pregnane-3,20-dione), minaxolone (11α-(dimethylamino)-2β-ethoxy-3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one), Org 20599 (21-chloro-3α-hydroxy-2β-morpholin-4-yl-5β-pregnan-20-one), Org 21465 (2β-(2,2-dimethyl-4-morpholinyl)-3α-hydroxy-11,20-dioxo-5α-pregnan-21-yl methanesulfonate), and renanolone (3α-hydroxy-5β-pregnan-11,20-dione).

Research

Allopregnanolone and the other endogenous inhibitory neurosteroids have short terminal half-lives and poor oral bioavailability, and for these reason, have not been pursued for clinical use as oral therapies, although development as a parenteral therapy for multiple indications has been carried out. However, synthetic analogs with improved pharmacokineticprofiles have been synthesized and are being investigated as potential oral therapeutic agents.

In other studies of compounds related to allopregnanolone, exogenous progesterone, such as oral micronized progesterone (OMP), elevates allopregnanolone levels in the body with good dose-to-serum level correlations.[35] Due to this, it has been suggested that OMP could be described as a prodrug of sorts for allopregnanolone.[35] As a result, there has been some interest in using OMP to treat catamenial epilepsy,[36] as well as other menstrual cycle-related and neurosteroid-associated conditions. In addition to OMP, oral pregnenolonehas also been found to act as a prodrug of allopregnanolone,[37][38][39] though also of pregnenolone sulfate.[40]

Allopregnanolone has been under development by Sage Therapeutics as an intravenously administered drug for the treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus, postpartum depression, and essential tremor.[41] As of 19 March 2019 the FDA has approved allopregnanolone for postpartum depression.

References

- ^ “ChemIDplus – 516-54-1 – AURFZBICLPNKBZ-SYBPFIFISA-N – Brexanolone [USAN] – Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information”. NIH Toxnet. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Reddy DS (2010). Neurosteroids: endogenous role in the human brain and therapeutic potentials. Prog. Brain Res. Progress in Brain Research. 186. pp. 113–37. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53630-3.00008-7. ISBN 9780444536303. PMC 3139029. PMID 21094889.

- ^ Reddy DS, Rogawski MA (2012). “Neurosteroids — Endogenous Regulators of Seizure Susceptibility and Role in the Treatment of Epilepsy”. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies, 4th Edition: 984–1002. doi:10.1093/med/9780199746545.003.0077. ISBN 9780199746545.

- ^ T. G. Kokate, B. E. Svensson & M. A. Rogawski (September 1994). “Anticonvulsant activity of neurosteroids: correlation with γ-aminobutyric acid-evoked chloride current potentiation”. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 270 (3): 1223–1229. PMID 7932175.

- ^ Pinna, G; Uzunova, V; Matsumoto, K; Puia, G; Mienville, J. -M; Costa, E; Guidotti, A (2000-03-01). “Brain allopregnanolone regulates the potency of the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol”. Neuropharmacology. 39 (3): 440–448. doi:10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00149-5. PMID 10698010.

- ^ Agís-Balboa, Roberto C.; Pinna, Graziano; Zhubi, Adrian; Maloku, Ekrem; Veldic, Marin; Costa, Erminio; Guidotti, Alessandro (2006-09-26). “Characterization of brain neurons that express enzymes mediating neurosteroid biosynthesis”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (39): 14602–14607. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606544103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1600006. PMID 16984997.

- ^ Mousavi Nik A, Pressly B, Singh V, Antrobus S, Hulsizer S, Rogawski MA, Wulff H, Pessah IN (2017). “Rapid Throughput Analysis of GABAA Receptor Subtype Modulators and Blockers Using DiSBAC1(3) Membrane Potential Red Dye”. Mol. Pharmacol. 92 (1): 88–99. doi:10.1124/mol.117.108563. PMC 5452057. PMID 28428226.

- ^ Morris KD, Moorefield CN, Amin J (October 1999). “Differential modulation of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type C receptor by neuroactive steroids”. Mol. Pharmacol. 56 (4): 752–9. PMID 10496958.

- ^ Li W, Jin X, Covey DF, Steinbach JH (October 2007). “Neuroactive steroids and human recombinant rho1 GABAC receptors”. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 323 (1): 236–47. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.127365. PMC 3905684. PMID 17636008.

- ^ Bullock AE, Clark AL, Grady SR, et al. (June 1997). “Neurosteroids modulate nicotinic receptor function in mouse striatal and thalamic synaptosomes”. J. Neurochem. 68 (6): 2412–23. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062412.x. PMID 9166735.

- ^ Wetzel CH, Hermann B, Behl C, et al. (September 1998). “Functional antagonism of gonadal steroids at the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor”. Mol. Endocrinol. 12 (9): 1441–51. doi:10.1210/mend.12.9.0163. PMID 9731711.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Mellon SH (October 2007). “Neurosteroid regulation of central nervous system development”. Pharmacol. Ther. 116 (1): 107–24. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.011. PMC 2386997. PMID 17651807.

- ^ Rupprecht R, Reul JM, Trapp T, et al. (September 1993). “Progesterone receptor-mediated effects of neuroactive steroids”. Neuron. 11 (3): 523–30. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(93)90156-l. PMID 8398145.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Thomas P, Pang Y (2012). “Membrane progesterone receptors: evidence for neuroprotective, neurosteroid signaling and neuroendocrine functions in neuronal cells”. Neuroendocrinology. 96 (2): 162–71. doi:10.1159/000339822. PMC 3489003. PMID 22687885.

- ^ Pang Y, Dong J, Thomas P (January 2013). “Characterization, neurosteroid binding and brain distribution of human membrane progesterone receptors δ and {epsilon} (mPRδ and mPR{epsilon}) and mPRδ involvement in neurosteroid inhibition of apoptosis”. Endocrinology. 154 (1): 283–95. doi:10.1210/en.2012-1772. PMC 3529379. PMID 23161870.

- ^ Sleiter N, Pang Y, Park C, et al. (August 2009). “Progesterone receptor A (PRA) and PRB-independent effects of progesterone on gonadotropin-releasing hormone release”. Endocrinology. 150 (8): 3833–44. doi:10.1210/en.2008-0774. PMC 2717864. PMID 19423765.

- ^ Lamba V, Yasuda K, Lamba JK, et al. (September 2004). “PXR (NR1I2): splice variants in human tissues, including brain, and identification of neurosteroids and nicotine as PXR activators”. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 199 (3): 251–65. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2003.12.027. PMID 15364541.

- ^ Hu AQ, Wang ZM, Lan DM, et al. (July 2007). “Inhibition of evoked glutamate release by neurosteroid allopregnanolone via inhibition of L-type calcium channels in rat medial prefrontal cortex”. Neuropsychopharmacology. 32 (7): 1477–89. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301261. PMID 17151597.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Earl DE, Tietz EI (April 2011). “Inhibition of recombinant L-type voltage-gated calcium channels by positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors”. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 337 (1): 301–11. doi:10.1124/jpet.110.178244. PMC 3063747. PMID 21262851.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Keitel V, Görg B, Bidmon HJ, et al. (November 2010). “The bile acid receptor TGR5 (Gpbar-1) acts as a neurosteroid receptor in brain”. Glia. 58 (15): 1794–805. doi:10.1002/glia.21049. PMID 20665558.

- ^ Rougé-Pont F, Mayo W, Marinelli M, Gingras M, Le Moal M, Piazza PV (July 2002). “The neurosteroid allopregnanolone increases dopamine release and dopaminergic response to morphine in the rat nucleus accumbens”. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16 (1): 169–73. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02084.x. PMID 12153544.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Frye CA (December 2009). “Neurosteroids’ effects and mechanisms for social, cognitive, emotional, and physical functions”. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34 Suppl 1: S143–61. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.005. PMC 2898141. PMID 19656632.

- ^ Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A (February 2005). “Changes in brain testosterone and allopregnanolone biosynthesis elicit aggressive behavior”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (6): 2135–40. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409643102. PMC 548579. PMID 15677716.

- ^ Terán-Pérez G, Arana-Lechuga Y, Esqueda-León E, Santana-Miranda R, Rojas-Zamorano JÁ, Velázquez Moctezuma J (October 2012). “Steroid hormones and sleep regulation”. Mini Rev Med Chem. 12 (11): 1040–8. doi:10.2174/138955712802762167. PMID 23092405.

- ^ Patte-Mensah C, Meyer L, Taleb O, Mensah-Nyagan AG (February 2014). “Potential role of allopregnanolone for a safe and effective therapy of neuropathic pain”. Prog. Neurobiol. 113: 70–8. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.004. PMID 23948490.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bäckström T, Andersson A, Andreé L, et al. (December 2003). “Pathogenesis in menstrual cycle-linked CNS disorders”. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1007: 42–53. doi:10.1196/annals.1286.005. PMID 14993039.

- ^ Guille C, Spencer S, Cavus I, Epperson CN (July 2008). “The role of sex steroids in catamenial epilepsy and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: implications for diagnosis and treatment”. Epilepsy Behav. 13 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.02.004. PMC 4112568. PMID 18346939.

- ^ Finocchi C, Ferrari M (May 2011). “Female reproductive steroids and neuronal excitability”. Neurol. Sci. 32 Suppl 1: S31–5. doi:10.1007/s10072-011-0532-5. PMID 21533709.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bäckström T, Haage D, Löfgren M, et al. (September 2011). “Paradoxical effects of GABA-A modulators may explain sex steroid induced negative mood symptoms in some persons”. Neuroscience. 191: 46–54. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.061. PMID 21600269.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Andréen L, Nyberg S, Turkmen S, van Wingen G, Fernández G, Bäckström T (September 2009). “Sex steroid induced negative mood may be explained by the paradoxical effect mediated by GABAA modulators”. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34 (8): 1121–32. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.003. PMID 19272715.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bäckström T, Bixo M, Johansson M, et al. (February 2014). “Allopregnanolone and mood disorders”. Prog. Neurobiol. 113: 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.005. PMID 23978486.

- ^ Andréen L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Nyberg S, Bäckström T (August 2006). “Allopregnanolone concentration and mood–a bimodal association in postmenopausal women treated with oral progesterone”. Psychopharmacology. 187 (2): 209–21. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0417-0. PMID 16724185.

- ^ Mellor DJ, Diesch TJ, Gunn AJ, Bennet L (2005). “The importance of ‘awareness’ for understanding fetal pain”. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 49 (3): 455–71. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.01.006. PMID 16269314.

- ^ Lagercrantz H, Changeux JP (2009). “The emergence of human consciousness: from fetal to neonatal life”. Pediatr. Res. 65 (3): 255–60. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181973b0d. PMID 19092726.

[…] the fetus is sedated by the low oxygen tension of the fetal blood and the neurosteroid anesthetics pregnanolone and the sleep-inducing prostaglandin D2 provided by the placenta (36).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Andréen L, Spigset O, Andersson A, Nyberg S, Bäckström T (June 2006). “Pharmacokinetics of progesterone and its metabolites allopregnanolone and pregnanolone after oral administration of low-dose progesterone”. Maturitas. 54 (3): 238–44. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.11.005. PMID 16406399.

- ^ Orrin Devinsky; Steven Schachter; Steven Pacia (1 January 2005). Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 378–. ISBN 978-1-934559-08-6.

- ^ Saudan C, Desmarchelier A, Sottas PE, Mangin P, Saugy M (2005). “Urinary marker of oral pregnenolone administration”. Steroids. 70 (3): 179–83. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2004.12.007. PMID 15763596.

- ^ Piper T, Schlug C, Mareck U, Schänzer W (2011). “Investigations on changes in ¹³C/¹²C ratios of endogenous urinary steroids after pregnenolone administration”. Drug Test Anal. 3(5): 283–90. doi:10.1002/dta.281. PMID 21538944.

- ^ Sripada RK, Marx CE, King AP, Rampton JC, Ho SS, Liberzon I (2013). “Allopregnanolone elevations following pregnenolone administration are associated with enhanced activation of emotion regulation neurocircuits”. Biol. Psychiatry. 73 (11): 1045–53. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.12.008. PMC 3648625. PMID 23348009.

- ^ Ducharme N, Banks WA, Morley JE, Robinson SM, Niehoff ML, Mattern C, Farr SA (2010). “Brain distribution and behavioral effects of progesterone and pregnenolone after intranasal or intravenous administration”. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 641 (2–3): 128–34. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.033. PMC 3008321. PMID 20570588.

- ^ “Brexanolone – Sage Therapeutics”. AdisInsight.

Further reading

- Herd, MB; Belelli, D; Lambert, JJ (2007). “Neurosteroid modulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors”. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 116 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.007. PMID 17531325.

|

|

|

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1-(3-Hydroxy-10,13-dimethyl-2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-tetradecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-17-yl)ethanone

|

|

| Other names

ALLO; Allo; ALLOP; AlloP; Brexanolone; 5α-Pregnan-3α-ol-20-one; 3α-Hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one; 3α,5α-Tetrahydroprogesterone; 3α,5α-THP; Zulresso

|

|

| Identifiers | |

|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

|

PubChemCID

|

|

| UNII | |

| Properties | |

| C21H34O2 | |

| Molar mass | 318.501 g·mol−1 |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

|

|

//////////

Brexanolone

318.501 g/mol, C21H34O2

CAS: 516-54-1

ブレキサノロン

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved Zulresso (brexanolone) injection for intravenous (IV) use for the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD) in adult women. This is the first drug approved by the FDA specifically for PPD.

March 19, 2019

Release

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved Zulresso (brexanolone) injection for intravenous (IV) use for the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD) in adult women. This is the first drug approved by the FDA specifically for PPD.

“Postpartum depression is a serious condition that, when severe, can be life-threatening. Women may experience thoughts about harming themselves or harming their child. Postpartum depression can also interfere with the maternal-infant bond. This approval marks the first time a drug has been specifically approved to treat postpartum depression, providing an important new treatment option,” said Tiffany Farchione, M.D., acting director of the Division of Psychiatry Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Because of concerns about serious risks, including excessive sedation or sudden loss of consciousness during administration, Zulresso has been approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) and is only available to patients through a restricted distribution program at certified health care facilities where the health care provider can carefully monitor the patient.”

PPD is a major depressive episode that occurs following childbirth, although symptoms can start during pregnancy. As with other forms of depression, it is characterized by sadness and/or loss of interest in activities that one used to enjoy and a decreased ability to feel pleasure (anhedonia) and may present with symptoms such as cognitive impairment, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, or suicidal ideation.

Zulresso will be available only through a restricted program called the Zulresso REMS Program that requires the drug be administered by a health care provider in a certified health care facility. The REMS requires that patients be enrolled in the program prior to administration of the drug. Zulresso is administered as a continuous IV infusion over a total of 60 hours (2.5 days). Because of the risk of serious harm due to the sudden loss of consciousness, patients must be monitored for excessive sedation and sudden loss of consciousness and have continuous pulse oximetry monitoring (monitors oxygen levels in the blood). While receiving the infusion, patients must be accompanied during interactions with their child(ren). The need for these steps is addressed in a Boxed Warning in the drug’s prescribing information. Patients will be counseled on the risks of Zulresso treatment and instructed that they must be monitored for these effects at a health care facility for the entire 60 hours of infusion. Patients should not drive, operate machinery, or do other dangerous activities until feelings of sleepiness from the treatment have completely gone away.

The efficacy of Zulresso was shown in two clinical studies in participants who received a 60-hour continuous intravenous infusion of Zulresso or placebo and were then followed for four weeks. One study included patients with severe PPD and the other included patients with moderate PPD. The primary measure in the study was the mean change from baseline in depressive symptoms as measured by a depression rating scale. In both placebo controlled studies, Zulresso demonstrated superiority to placebo in improvement of depressive symptoms at the end of the first infusion. The improvement in depression was also observed at the end of the 30-day follow-up period.

The most common adverse reactions reported by patients treated with Zulresso in clinical trials include sleepiness, dry mouth, loss of consciousness and flushing. Health care providers should consider changing the therapeutic regimen, including discontinuing Zulresso in patients whose PPD becomes worse or who experience emergent suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

The FDA granted this application Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapydesignation.

Approval of Zulresso was granted to Sage Therapeutics, Inc.

Allopregnanolone, also known as 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one or 3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone (3α,5α-THP), as well as brexanolone (USAN),[1] is an endogenous inhibitory pregnane neurosteroid[2] which has been approved by the FDA as a treatment for post-partum depression. It is synthesized from progesterone, and is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the action of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at GABAA receptor.[2] Allopregnanolone has effects similar to those of other positive allosteric modulators of the GABA action at GABAA receptor such as the benzodiazepines, including anxiolytic, sedative, and anticonvulsant activity.[2][3][4] Endogenously produced allopregnanolone exerts a pivotal neurophysiological role by fine-tuning of GABAA receptor and modulating the action of several positive allosteric modulators and agonists at GABAA receptor.[5] The 21-hydroxylated derivative of this compound, tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC), is an endogenous inhibitory neurosteroid with similar properties to those of allopregnanolone, and the 3β-methyl analogue of allopregnanolone, ganaxolone, is under development to treat epilepsy and other conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[2]

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of allopregnanolone in the brain starts with the conversion of progesterone into 5α-dihydroprogesterone by 5α-reductase type I. After that, 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase converts this intermediate into allopregnanolone.[2] Allopregnanolone in the brain is produced by cortical and hippocampus pyramidal neurons and pyramidal-like neurons of the basolateral amygdala.[6]

Biological activity

Allopregnanolone acts as a highly potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor.[2] While allopregnanolone, like other inhibitory neurosteroids such as THDOC, positively modulates all GABAA receptor isoforms, those isoforms containing δ subunitsexhibit the greatest potentiation.[7] Allopregnanolone has also been found to act as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA-ρ receptor, though the implications of this action are unclear.[8][9] In addition to its actions on GABA receptors, allopregnanolone, like progesterone, is known to be a negative allosteric modulator of nACh receptors,[10] and also appears to act as a negative allosteric modulator of the 5-HT3 receptor.[11] Along with the other inhibitory neurosteroids, allopregnanolone appears to have little or no action at other ligand-gated ion channels, including the NMDA, AMPA, kainate, and glycine receptors.[12]

Unlike progesterone, allopregnanolone is inactive at the nuclear progesterone receptor (nPR).[12] However, allopregnanolone can be intracellularly oxidized into 5α-dihydroprogesterone, which is an agonist of the nPR, and thus/in accordance, allopregnanolone does appear to have indirect nPR-mediated progestogenic effects.[13] In addition, allopregnanolone has recently been found to be an agonist of the newly discovered membrane progesterone receptors (mPR), including mPRδ, mPRα, and mPRβ, with its activity at these receptors about a magnitude more potent than at the GABAA receptor.[14][15] The action of allopregnanolone at these receptors may be related, in part, to its neuroprotective and antigonadotropic properties.[14][16] Also like progesterone, recent evidence has shown that allopregnanolone is an activator of the pregnane X receptor.[12][17]

Similarly to many other GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators, allopregnanolone has been found to act as an inhibitor of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (L-VGCCs),[18] including α1 subtypes Cav1.2 and Cav1.3.[19] However, the threshold concentration of allopregnanolone to inhibit L-VGCCs was determined to be 3 μM (3,000 nM), which is far greater than the concentration of 5 nM that has been estimated to be naturally produced in the human brain.[19] Thus, inhibition of L-VGCCs is unlikely of any actual significance in the effects of endogenous allopregnanolone.[19] Also, allopregnanolone, along with several other neurosteroids, has been found to activate the G protein-coupled bile acid receptor (GPBAR1, or TGR5).[20] However, it is only able to do so at micromolar concentrations, which, similarly to the case of the L-VGCCs, are far greater than the low nanomolar concentrations of allopregnanolone estimated to be present in the brain.[20]

Biological function

Allopregnanolone possesses a wide variety of effects, including, in no particular order, antidepressant, anxiolytic, stress-reducing, rewarding,[21] prosocial,[22] antiaggressive,[23]prosexual,[22] sedative, pro-sleep,[24] cognitive, memory-impairment, analgesic,[25] anesthetic, anticonvulsant, neuroprotective, and neurogenic effects.[2] Fluctuations in the levels of allopregnanolone and the other neurosteroids seem to play an important role in the pathophysiology of mood, anxiety, premenstrual syndrome, catamenial epilepsy, and various other neuropsychiatric conditions.[26][27][28]

Increased levels of allopregnanolone can produce paradoxical effects, including negative mood, anxiety, irritability, and aggression.[29][30][31] This appears to be because allopregnanolone possesses biphasic, U-shaped actions at the GABAA receptor – moderate level increases (in the range of 1.5–2 nM/L total allopregnanolone, which are approximately equivalent to luteal phase levels) inhibit the activity of the receptor, while lower and higher concentration increases stimulate it.[29][30] This seems to be a common effect of many GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators.[26][31] In accordance, acute administration of low doses of micronized progesterone (which reliably elevates allopregnanolone levels) has been found to have negative effects on mood, while higher doses have a neutral effect.[32]

During pregnancy, allopregnanolone and pregnanolone are involved in sedation and anesthesia of the fetus.[33][34]

Chemistry

Allopregnanolone is a pregnane (C21) steroid and is also known as 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one, 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one, or 3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone (3α,5α-THP). It is very closely related structurally to 5-pregnenolone (pregn-5-en-3β-ol-20-dione), progesterone (pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione), the isomers of pregnanedione (5-dihydroprogesterone; 5-pregnane-3,20-dione), the isomers of 4-pregnenolone (3-dihydroprogesterone; pregn-4-en-3-ol-20-one), and the isomers of pregnanediol (5-pregnane-3,20-diol). In addition, allopregnanolone is one of four isomers of pregnanolone (3,5-tetrahydroprogesterone), with the other three isomers being pregnanolone (5β-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one), isopregnanolone(5α-pregnan-3β-ol-20-one), and epipregnanolone (5β-pregnan-3β-ol-20-one).

Derivatives

A variety of synthetic derivatives and analogues of allopregnanolone with similar activity and effects exist, including alfadolone (3α,21-dihydroxy-5α-pregnane-11,20-dione), alfaxolone (3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnane-11,20-dione), ganaxolone (3α-hydroxy-3β-methyl-5α-pregnan-20-one), hydroxydione (21-hydroxy-5β-pregnane-3,20-dione), minaxolone (11α-(dimethylamino)-2β-ethoxy-3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one), Org 20599 (21-chloro-3α-hydroxy-2β-morpholin-4-yl-5β-pregnan-20-one), Org 21465 (2β-(2,2-dimethyl-4-morpholinyl)-3α-hydroxy-11,20-dioxo-5α-pregnan-21-yl methanesulfonate), and renanolone (3α-hydroxy-5β-pregnan-11,20-dione).

Research

Allopregnanolone and the other endogenous inhibitory neurosteroids have short terminal half-lives and poor oral bioavailability, and for these reason, have not been pursued for clinical use as oral therapies, although development as a parenteral therapy for multiple indications has been carried out. However, synthetic analogs with improved pharmacokineticprofiles have been synthesized and are being investigated as potential oral therapeutic agents.

In other studies of compounds related to allopregnanolone, exogenous progesterone, such as oral micronized progesterone (OMP), elevates allopregnanolone levels in the body with good dose-to-serum level correlations.[35] Due to this, it has been suggested that OMP could be described as a prodrug of sorts for allopregnanolone.[35] As a result, there has been some interest in using OMP to treat catamenial epilepsy,[36] as well as other menstrual cycle-related and neurosteroid-associated conditions. In addition to OMP, oral pregnenolonehas also been found to act as a prodrug of allopregnanolone,[37][38][39] though also of pregnenolone sulfate.[40]

Allopregnanolone has been under development by Sage Therapeutics as an intravenously administered drug for the treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus, postpartum depression, and essential tremor.[41] As of 19 March 2019 the FDA has approved allopregnanolone for postpartum depression.

References

- ^ “ChemIDplus – 516-54-1 – AURFZBICLPNKBZ-SYBPFIFISA-N – Brexanolone [USAN] – Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information”. NIH Toxnet. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Reddy DS (2010). Neurosteroids: endogenous role in the human brain and therapeutic potentials. Prog. Brain Res. Progress in Brain Research. 186. pp. 113–37. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53630-3.00008-7. ISBN 9780444536303. PMC 3139029. PMID 21094889.

- ^ Reddy DS, Rogawski MA (2012). “Neurosteroids — Endogenous Regulators of Seizure Susceptibility and Role in the Treatment of Epilepsy”. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies, 4th Edition: 984–1002. doi:10.1093/med/9780199746545.003.0077. ISBN 9780199746545.

- ^ T. G. Kokate, B. E. Svensson & M. A. Rogawski (September 1994). “Anticonvulsant activity of neurosteroids: correlation with γ-aminobutyric acid-evoked chloride current potentiation”. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 270 (3): 1223–1229. PMID 7932175.

- ^ Pinna, G; Uzunova, V; Matsumoto, K; Puia, G; Mienville, J. -M; Costa, E; Guidotti, A (2000-03-01). “Brain allopregnanolone regulates the potency of the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol”. Neuropharmacology. 39 (3): 440–448. doi:10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00149-5. PMID 10698010.

- ^ Agís-Balboa, Roberto C.; Pinna, Graziano; Zhubi, Adrian; Maloku, Ekrem; Veldic, Marin; Costa, Erminio; Guidotti, Alessandro (2006-09-26). “Characterization of brain neurons that express enzymes mediating neurosteroid biosynthesis”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (39): 14602–14607. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606544103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1600006. PMID 16984997.

- ^ Mousavi Nik A, Pressly B, Singh V, Antrobus S, Hulsizer S, Rogawski MA, Wulff H, Pessah IN (2017). “Rapid Throughput Analysis of GABAA Receptor Subtype Modulators and Blockers Using DiSBAC1(3) Membrane Potential Red Dye”. Mol. Pharmacol. 92 (1): 88–99. doi:10.1124/mol.117.108563. PMC 5452057. PMID 28428226.

- ^ Morris KD, Moorefield CN, Amin J (October 1999). “Differential modulation of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type C receptor by neuroactive steroids”. Mol. Pharmacol. 56 (4): 752–9. PMID 10496958.

- ^ Li W, Jin X, Covey DF, Steinbach JH (October 2007). “Neuroactive steroids and human recombinant rho1 GABAC receptors”. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 323 (1): 236–47. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.127365. PMC 3905684. PMID 17636008.

- ^ Bullock AE, Clark AL, Grady SR, et al. (June 1997). “Neurosteroids modulate nicotinic receptor function in mouse striatal and thalamic synaptosomes”. J. Neurochem. 68 (6): 2412–23. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062412.x. PMID 9166735.

- ^ Wetzel CH, Hermann B, Behl C, et al. (September 1998). “Functional antagonism of gonadal steroids at the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor”. Mol. Endocrinol. 12 (9): 1441–51. doi:10.1210/mend.12.9.0163. PMID 9731711.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Mellon SH (October 2007). “Neurosteroid regulation of central nervous system development”. Pharmacol. Ther. 116 (1): 107–24. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.011. PMC 2386997. PMID 17651807.

- ^ Rupprecht R, Reul JM, Trapp T, et al. (September 1993). “Progesterone receptor-mediated effects of neuroactive steroids”. Neuron. 11 (3): 523–30. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(93)90156-l. PMID 8398145.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Thomas P, Pang Y (2012). “Membrane progesterone receptors: evidence for neuroprotective, neurosteroid signaling and neuroendocrine functions in neuronal cells”. Neuroendocrinology. 96 (2): 162–71. doi:10.1159/000339822. PMC 3489003. PMID 22687885.

- ^ Pang Y, Dong J, Thomas P (January 2013). “Characterization, neurosteroid binding and brain distribution of human membrane progesterone receptors δ and {epsilon} (mPRδ and mPR{epsilon}) and mPRδ involvement in neurosteroid inhibition of apoptosis”. Endocrinology. 154 (1): 283–95. doi:10.1210/en.2012-1772. PMC 3529379. PMID 23161870.

- ^ Sleiter N, Pang Y, Park C, et al. (August 2009). “Progesterone receptor A (PRA) and PRB-independent effects of progesterone on gonadotropin-releasing hormone release”. Endocrinology. 150 (8): 3833–44. doi:10.1210/en.2008-0774. PMC 2717864. PMID 19423765.

- ^ Lamba V, Yasuda K, Lamba JK, et al. (September 2004). “PXR (NR1I2): splice variants in human tissues, including brain, and identification of neurosteroids and nicotine as PXR activators”. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 199 (3): 251–65. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2003.12.027. PMID 15364541.

- ^ Hu AQ, Wang ZM, Lan DM, et al. (July 2007). “Inhibition of evoked glutamate release by neurosteroid allopregnanolone via inhibition of L-type calcium channels in rat medial prefrontal cortex”. Neuropsychopharmacology. 32 (7): 1477–89. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301261. PMID 17151597.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Earl DE, Tietz EI (April 2011). “Inhibition of recombinant L-type voltage-gated calcium channels by positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors”. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 337 (1): 301–11. doi:10.1124/jpet.110.178244. PMC 3063747. PMID 21262851.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Keitel V, Görg B, Bidmon HJ, et al. (November 2010). “The bile acid receptor TGR5 (Gpbar-1) acts as a neurosteroid receptor in brain”. Glia. 58 (15): 1794–805. doi:10.1002/glia.21049. PMID 20665558.

- ^ Rougé-Pont F, Mayo W, Marinelli M, Gingras M, Le Moal M, Piazza PV (July 2002). “The neurosteroid allopregnanolone increases dopamine release and dopaminergic response to morphine in the rat nucleus accumbens”. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16 (1): 169–73. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02084.x. PMID 12153544.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Frye CA (December 2009). “Neurosteroids’ effects and mechanisms for social, cognitive, emotional, and physical functions”. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34 Suppl 1: S143–61. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.005. PMC 2898141. PMID 19656632.

- ^ Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A (February 2005). “Changes in brain testosterone and allopregnanolone biosynthesis elicit aggressive behavior”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (6): 2135–40. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409643102. PMC 548579. PMID 15677716.

- ^ Terán-Pérez G, Arana-Lechuga Y, Esqueda-León E, Santana-Miranda R, Rojas-Zamorano JÁ, Velázquez Moctezuma J (October 2012). “Steroid hormones and sleep regulation”. Mini Rev Med Chem. 12 (11): 1040–8. doi:10.2174/138955712802762167. PMID 23092405.

- ^ Patte-Mensah C, Meyer L, Taleb O, Mensah-Nyagan AG (February 2014). “Potential role of allopregnanolone for a safe and effective therapy of neuropathic pain”. Prog. Neurobiol. 113: 70–8. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.004. PMID 23948490.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bäckström T, Andersson A, Andreé L, et al. (December 2003). “Pathogenesis in menstrual cycle-linked CNS disorders”. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1007: 42–53. doi:10.1196/annals.1286.005. PMID 14993039.

- ^ Guille C, Spencer S, Cavus I, Epperson CN (July 2008). “The role of sex steroids in catamenial epilepsy and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: implications for diagnosis and treatment”. Epilepsy Behav. 13 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.02.004. PMC 4112568. PMID 18346939.

- ^ Finocchi C, Ferrari M (May 2011). “Female reproductive steroids and neuronal excitability”. Neurol. Sci. 32 Suppl 1: S31–5. doi:10.1007/s10072-011-0532-5. PMID 21533709.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bäckström T, Haage D, Löfgren M, et al. (September 2011). “Paradoxical effects of GABA-A modulators may explain sex steroid induced negative mood symptoms in some persons”. Neuroscience. 191: 46–54. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.061. PMID 21600269.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Andréen L, Nyberg S, Turkmen S, van Wingen G, Fernández G, Bäckström T (September 2009). “Sex steroid induced negative mood may be explained by the paradoxical effect mediated by GABAA modulators”. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34 (8): 1121–32. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.003. PMID 19272715.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bäckström T, Bixo M, Johansson M, et al. (February 2014). “Allopregnanolone and mood disorders”. Prog. Neurobiol. 113: 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.005. PMID 23978486.

- ^ Andréen L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Nyberg S, Bäckström T (August 2006). “Allopregnanolone concentration and mood–a bimodal association in postmenopausal women treated with oral progesterone”. Psychopharmacology. 187 (2): 209–21. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0417-0. PMID 16724185.

- ^ Mellor DJ, Diesch TJ, Gunn AJ, Bennet L (2005). “The importance of ‘awareness’ for understanding fetal pain”. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 49 (3): 455–71. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.01.006. PMID 16269314.

- ^ Lagercrantz H, Changeux JP (2009). “The emergence of human consciousness: from fetal to neonatal life”. Pediatr. Res. 65 (3): 255–60. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181973b0d. PMID 19092726.

[…] the fetus is sedated by the low oxygen tension of the fetal blood and the neurosteroid anesthetics pregnanolone and the sleep-inducing prostaglandin D2 provided by the placenta (36).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Andréen L, Spigset O, Andersson A, Nyberg S, Bäckström T (June 2006). “Pharmacokinetics of progesterone and its metabolites allopregnanolone and pregnanolone after oral administration of low-dose progesterone”. Maturitas. 54 (3): 238–44. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.11.005. PMID 16406399.

- ^ Orrin Devinsky; Steven Schachter; Steven Pacia (1 January 2005). Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 378–. ISBN 978-1-934559-08-6.

- ^ Saudan C, Desmarchelier A, Sottas PE, Mangin P, Saugy M (2005). “Urinary marker of oral pregnenolone administration”. Steroids. 70 (3): 179–83. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2004.12.007. PMID 15763596.

- ^ Piper T, Schlug C, Mareck U, Schänzer W (2011). “Investigations on changes in ¹³C/¹²C ratios of endogenous urinary steroids after pregnenolone administration”. Drug Test Anal. 3(5): 283–90. doi:10.1002/dta.281. PMID 21538944.

- ^ Sripada RK, Marx CE, King AP, Rampton JC, Ho SS, Liberzon I (2013). “Allopregnanolone elevations following pregnenolone administration are associated with enhanced activation of emotion regulation neurocircuits”. Biol. Psychiatry. 73 (11): 1045–53. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.12.008. PMC 3648625. PMID 23348009.

- ^ Ducharme N, Banks WA, Morley JE, Robinson SM, Niehoff ML, Mattern C, Farr SA (2010). “Brain distribution and behavioral effects of progesterone and pregnenolone after intranasal or intravenous administration”. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 641 (2–3): 128–34. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.033. PMC 3008321. PMID 20570588.

- ^ “Brexanolone – Sage Therapeutics”. AdisInsight.

Further reading

- Herd, MB; Belelli, D; Lambert, JJ (2007). “Neurosteroid modulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors”. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 116 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.007. PMID 17531325.

|

|

|

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1-(3-Hydroxy-10,13-dimethyl-2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-tetradecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-17-yl)ethanone

|

|

| Other names

ALLO; Allo; ALLOP; AlloP; Brexanolone; 5α-Pregnan-3α-ol-20-one; 3α-Hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one; 3α,5α-Tetrahydroprogesterone; 3α,5α-THP; Zulresso

|

|

| Identifiers | |

|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

|

PubChemCID

|

|

| UNII | |

| Properties | |

| C21H34O2 | |

| Molar mass | 318.501 g·mol−1 |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

|

|

//////////Brexanolone, Priority Review, Breakthrough Therapy designation, Zulresso, Sage Therapeutics Inc, FDA 2019, ブレキサノロン , Brexanolone, Allopregnanolone

CC(=O)C1CCC2C1(CCC3C2CCC4C3(CCC(C4)O)C)C

CC(=O)C1CCC2C1(CCC3C2CCC4C3(CCC(C4)O)C)C