Cladribine

クラドリビン

Leustatin

RWJ 26251 / RWJ-26251

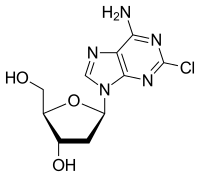

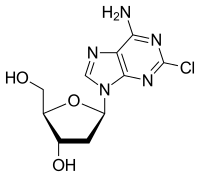

- Molecular FormulaC10H12ClN5O3

- Average mass285.687 Da

Cladribine, sold under the brand name Leustatin and Mavenclad among others, is a medication used to treat hairy cell leukemia(HCL, leukemic reticuloendotheliosis), B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.[4][5] Its chemical name is 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine (2CdA).

Cladribine, a deoxyadenosine derivative developed by Ortho Biotech (currently Janssen), was first launched in the U.S. in 1993 as an intravenous treatment for hairy cell leukemia

Cladribine has been granted orphan drug designation in the U.S. in 1990 for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and hairy cell leukemia

As a purine analog, it is a synthetic chemotherapy agent that targets lymphocytes and selectively suppresses the immune system. Chemically, it mimics the nucleoside adenosine. However, unlike adenosine it is relatively resistant to breakdown by the enzyme adenosine deaminase, which causes it to accumulate in cells and interfere with the cell’s ability to process DNA. Cladribine is taken up cells via a transporter. Once inside a cell cladribine is activated mostly in lymphocytes, when it is triphosphorylated by the enzyme deoxyadenosine kinase (dCK). Various phosphatases dephosphorylate cladribine. Activated, triphosphorylated, cladribine is incorporated into mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, which triggers apoptosis. Non-activated cladribine is removed quickly from all other cells. This means that there is very little non-target cell loss.[4][6]

Medical uses

Cladribine is used for as a first and second-line treatment for symptomatic hairy cell leukemia and for B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is administered by intravenous or subcutaneous infusion.[5][7]

Since 2017, cladribine is approved as an oral formulation (10 mg tablet) for the treatment of RRMS in Europe, UAE, Argentina, Chile, Canada and Australia. Marketing authorization in the US was obtained in March 2019[8].

Some investigators have used the parenteral formulation orally to treat patients with HCL. It is important to note that approximately 40% of oral cladribine in bioavailable orally. It used, often in combination with other cytotoxic agents, to treat various kinds of histiocytosis, including Erdheim–Chester disease[9] and Langerhans cell histiocytosis,[10]

Cladribine can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman and is listed by the FDA as Pregnancy Category D; safety and efficacy in children has not been established.[7]

Adverse effects

Injectable cladribine suppresses the body’s ability to make new lymphocytes, natural killer cells and neutrophils (called myelosuppression); data from HCL studies showed that about 70% of people taking the drug had fewer white blood cells and about 30% developed infections and some of those progressed to septic shock; about 40% of people taking the drug had fewer red blood cells and became severely anemic; and about 10% of people had too few platelets.[7]

At the dosage used to treat HCL in two clinical trials, 16% of people had rashes and 22% had nausea, the nausea generally did not lead to vomiting.[7]

In comparison, in MS, cladribine is associated with a 6% rate of severe lymphocyte suppression (lymphopenia) (levels lower than 50% of normal). Other common side effects include headache (75%), sore throat (56%), common cold-like illness (42%) and nausea (39%)[11]

Mechanism of Action

As a purine analogue, it is taken up into rapidly proliferating cells like lymphocytes to be incorporated into DNA synthesis. Unlike adenosine, cladribine has a chlorine molecule at position 2, which renders it partially resistant to breakdown by adenosine deaminase (ADA). In cells it is phosphorylated into its toxic form, deoxyadenosine triphosphate, by the enzyme deoxycytidine kinase (DCK). This molecule is then incorporated into the DNA synthesis pathway, where it causes strand breakage. This is followed by the activation of transcription factor p53, the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and eventual programmed cell death (apoptosis).[12] This process occurs over approximately 2 months, with a peak level of cell depletion 4–8 weeks after treatment[13]

Within the lymphocyte pool, cladribine targets B cells more than T cells. Both HCL and B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia are types of B cell blood cancers. In MS, its effectiveness may be due to its ability to effectively deplete B cells, in particular memory B cells[14] In the pivotal phase 3 clinical trial of oral cladribine in MS, CLARITY, cladribine selectively depleted 80% of peripheral B cells, compared to only 40-50% of total T cells.[15] More recently, cladribine has been shown to induce long term, selective suppression of certain subtypes of B cells, especially memory B cells.[16]

Another family of enzymes, the 5´nucleotidase (5NCT) family, is also capable of dephosphorylating cladribine, making it inactive. The most important subtype of this group appears to be 5NCT1A, which is cytosolically active and specific for purine analogues. When DCK gene expression is expressed as a ratio with 5NCT1A, the cells with the highest ratios are B cells, especially germinal centre and naive B cells.[16] This again helps to explain which B cells are more vulnerable to cladribine-mediated apoptosis.

Although cladribine is selective for B cells, the long term suppression of memory B cells, which may contribute to its effect in MS, is not explained by gene or protein expression. Instead, cladribine appears to deplete the entire B cell department. However, while naive B cells rapidly move from lymphoid organs, the memory B cell pool repopulates very slowly from the bone marrow.

History

Ernest Beutler and Dennis A. Carson had studied adenosine deaminase deficiency and recognized that because the lack of adenosine deaminase led to the destruction of B cell lymphocytes, a drug designed to inhibit adenosine deaminase might be useful in lymphomas. Carson then synthesized cladribine, and through clinical research at Scripps starting in the 1980s, Beutler tested it as intravenous infusion and found it was especially useful to treat hairy cell leukemia (HCL). No pharmaceutical companies were interested in selling the drug because HCL was an orphan disease, so Beutler’s lab synthesized and packaged it and supplied it to the hospital pharmacy; the lab also developed a test to monitor blood levels. This was the first treatment that led to prolonged remission of HCL, which was previously untreatable.[17]:14–15

In February 1991 Scripps began a collaboration with Johnson & Johnson to bring intravenous cladribine to market and by December of that year J&J had filed an NDA; cladrabine was approved by the FDA in 1993 for HCL as an orphan drug,[18] and was approved in Europe later that year.[19]:2

The subcutaneous formulation was developed in Switzerland in the early 1990s and it was commercialized by Lipomed GmbH in the 2000s.[19]:2[20]

Multiple sclerosis

In the mid-1990s Beutler, in collaboration with Jack Sipe, a neurologist at Scripps, ran several clinical trials exploring the utility of cladribine in multiple sclerosis, based on the drug’s immunosuppressive effects. Sipe’s insight into MS, and Beutler’s interest in MS due to his sister’s having had it, led a very productive collaboration.[17]:17[21] Ortho-Clinical, a subsidiary of J&J, filed an NDA for cladribine for MS in 1997 but withdrew it in the late 1990s after discussion with the FDA proved that more clinical data would be needed.[22][23]

Ivax acquired the rights for oral administration of cladribine to treat MS from Scripps in 2000,[24] and partnered with Serono in 2002.[23] Ivax was acquired by Teva in 2006,[25][26] and Merck KGaA acquired control of Serono’s drug business in 2006.[27]

An oral formulation of the drug with cyclodextrin was developed[28]:16 and Ivax and Serono, and then Merck KGaA conducted several clinical studies. Merck KGaA submitted an application to the European Medicines Agency in 2009, which was rejected in 2010, and an appeal was denied in 2011.[28]:4–5 Likewise Merck KGaA’s NDA with the FDA rejected in 2011.[29] The concerns were that several cases of cancer had arisen, and the ratio of benefit to harm was not clear to regulators.[28]:54–55 The failures with the FDA and the EMA were a blow to Merck KGaA and were one of a series of events that led to a reorganization, layoffs, and closing the Swiss facility where Serono had arisen.[30][31] However, several MS clinical trials were still ongoing at the time of the rejections, and Merck KGaA committed to completing them.[29] A meta-analysis of data from clinical trials showed that cladiribine did not increase the risk of cancer at the doses used in the clinical trials.[32]

In 2015 Merck KGaA announced it would again seek regulatory approval with data from the completed clinical trials in hand,[30] and in 2016 the EMA accepted its application for review.[33] On June 22, 2017, the EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorisation for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis.[34]

Finally, after all these problems it was approved in Europe on August 2017 for highly active RRMS.[35]

Efficacy

Cladribine is an effective treatment for relapsing remitting MS, with a reduction in the annual rate of relapses of 54.5%.[11] These effects may be sustained up to 4 years after initial treatment, even if no further doses are given.[36] Thus, cladribine is considered to be a highly effective immune reconstitution therapy in MS. Similar to alemtuzumab, cladribine is given as two courses approximately one year apart. Each course consists of 4-5 tablets given over a week in the first month, followed by a second dosing of another 4-5 tablets the following month[37] During this time and after the final dose patients are monitored for adverse effects and signs of relapse.

https://www.merckneurology.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/mavenclad-table-1.jpg

Safety

Compared to alemtuzumab, cladribine is associated with a lower rate of severe lymphopenia. It also appears to have a lower rate of common adverse events, especially mild to moderate infections[11][36] As cladribine is not a recombinant biological therapy, it is not associated with the development of antibodies against the drug, which might reduce the effectiveness of future doses. Also, unlike alemtuzumab, cladribine is not associated with secondary autoimmunity.[38]

This is probably due to the fact cladribine more selectively targets B cells. Unlike alemtuzumab, cladribine is not associated with a rapid repopulation of the peripheral blood B cell pool, which then ´overshoots´ the original number by up to 30%.[39] Instead, B cells repopulate more slowly, reaching near normal total B cells numbers at 1 year. This phenomenon and the relative sparing of T cells, some of which might be important in regulating the system against other autoimmune reactions, is thought to explain the lack of secondary autoimmunity.

Use in clinical practice

The decision to start cladribine in MS depends on the degree of disease activity (as measured by number of relapses in the past year and T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions on MRI), the failure of previous disease-modifying therapies, the potential risks and benefits and patient choice.

In the UK, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends cladribine for treating highly active RRMS in adults if the persons has:

rapidly evolving severe relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis, that is, at least 2 relapses in the previous year and at least 1 T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesion at baseline MRI or

relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis that has responded inadequately to treatment with disease-modifying therapy, defined as 1 relapse in the previous year and MRI evidence of disease activity.[40]

People with MS require counselling on the intended benefits of cladribine in reducing the risk of relapse and disease progression, versus the risk of adverse effects such as headaches, nausea and mild to moderate infections. Women of childbearing age also require counselling that they should not conceive while taking cladribine, due to the risk of harm to the fetus.

Cladribine, as the 10 mg oral preparation Mavenclad, is administered as two courses of tablets approximately one year apart. Each course consists of four to five treatment days in the first month, followed by an additional four to five treatment days in the second month. The recommended dose of Mavenclad is 3.5 mg/kg over 2 years, given in two treatment courses of 1.75 mg/kg/year. Therefore, the number of tablets administered on each treatment day depends on the person’s weight. A full guide to the dosing strategy can be found below:

https://www.merckneurology.co.uk/mavenclad/mavenclad-efficacy/

After treatment, people with MS are monitored with regular blood tests, looking specifically at the white cell count and liver function. Patients should be followed up regularly by their treating neurologist to assess efficacy, and should be able to contact their MS service in the case of adverse effects or relapse. After the first two years of active treatment no further therapy may need to be given, as cladribine has been shown to be efficacious for up to last least four years after treatment. However, if patients fail to respond, options include switching to other highly effective disease-modifying therapies such as alemtuzumab, fingolimod or natalizumab.

Research directions

Cladribine has been studied as part of a multi-drug chemotherapy regimen for drug-resistant T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia.[41]

REF

A universal biocatalyst for the preparation of base- and sugar-modified nucleosides via an enzymatic transglycosylation

Helv Chim Acta 2002, 85(7): 1901

Synthesis of 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine by microbiological transglycosylation

Nucleosides Nucleotides 1993, 12(3-4): 417

Synthesis of 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine by washed cells of E. coli

Biotechnol Lett 1992, 14(8): 669

Efficient syntheses of 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine (cladribine) from 2′-deoxyguanosine

J Org Chem 2003, 68(3): 989

WO 2004028462

Synthesis of 2′-deoxytubercidin, 2′-deoxyadenosine, and related 2′-deoxynucleosides via a novel direct stereospecific sodium salt glycosylation procedure

J Am Chem Soc 1984, 106(21): 6379

WO 2011113476

A stereoselective process for the manufacture of a 2′-deoxy-beta-D-ribonucleoside using the vorbruggen glycosylation

Org Process Res Dev 2013, 17(11): 1419

A new synthesis of 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine (Cladribine), CdA)

Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2011, 30(5): 353

A dramatic concentration effect on the stereoselectivity of N-glycosylation for the synthesis of 2′-deoxy-beta-ribonucleosides

Chem Commun (London) 2012, 48(56): 7097

CN 105367616

PATENT

https://patents.google.com/patent/EP2891660A1/en

Previously Robins and Robins (Robins, M. J. and Robins, R. K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 4934-4940) reported that acid-catalyzed fusion of 1,3,5-tri-O-acety-2-deoxy-D-ribofuranose and 2,6-dichloropurine gave a 65% yield of an anomeric mixture 2,6-dichloro-9-(3′,5′-di-O-acetyl-2′-deoxy-α-,β-D-ribofuranosyl)-purines from which the α-anomer was obtained as a pure crystalline product by fractional crystallization from ethanol in 32% yield and the equivalent β-anomer remained in the mother liquor (see Scheme 1). The β-anomer, which could have been used to synthesize cladribine, wasn’t isolated further. The α-anomer was treated with methanolic ammonia which resulted in simultaneous deacetylation and amination to give 6-amino-2-chloro-9-(2′-deoxy-α-D-ribofuranosyl)-purine, which is a diastereomer of cladribine.

[0004]

Broom et al. (Christensen, L. F., Broom, A. D., Robins, M. J., and Bloch, A., J. Med. Chem. 1972, 15, 735-739) adapted Robins et al.’s method by treating the acetylated mixture (viz., 2,6-dichloro-9-(3′,5′-di-O-acety-2′-deoxy-α,β-D-ribofuranosyl)-purine) with liquid ammonia and reacylating the resulting 2′-deoxy-α-and –β-adenosines with p-toluoyl chloride (see Scheme 2). The desired 2-chloro-9-(3′,5′-di-O–p-toluoyl-2′-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl)-adenine was then separated by chromatography and removal of the p-toluoyl group resulted in cladribine in 9% overall yield based on the fusion of 1,3,5-tri-O-acety-2-deoxy-D-ribofuranose and 2,6-dichloropurine.

To increase the stereoselectivity in favour of the β-anomer, Robins et al.(Robins, R. L. et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 6379-6382, US4760137 , EP0173059 ) provided an improved method in which the sodium salt of 2,6-dichloropurine was coupled with 1-chloro-2-deoxy-3,5-di-O–p-toluoyl-α-D-ribofuranose in acetonitrile (MeCN) to give the protected β-nucleoside in 59% isolated yield, following chromatography and crystallisation, in addition to 13% of the undesired N-7 regioisomer (see Scheme 3). The apparently higher selectivity in this coupling reaction is attributed to it being a direct SN2 displacement of the chloride ion by the purine sodium salt. The protected N-9 2′-deoxy-β-nucleoside was treated with methanolic ammonia at 100°C to give cladribine in an overall 42% yield. The drawback of this process is that the nucleophilic 7- position nitrogen competes in the SN2 reaction against the nucleophilic 9- position, leading to a mixture of the N-7 and N-9 glycosyl isomers as well as the need for chromatography and crystallisation to obtain the pure desired isomer.

Gerszberg and Alonso (Gerszberg S. and Alonso, D. WO0064918 , and US20020052491 ) also utilised an SN2 approach with 1-chloro-2-deoxy-3,5-di-O–p-toluoyl-α-D-ribofuranose but instead coupled it with the sodium salt of 2-chloroadenine in acetone giving the desired β-anomer of the protected cladribine in 60% yield following crystallisation from ethanol (see Scheme 4). After the deprotection step using ammonia in methanol (MeOH), the β-anomer of cladribine was isolated in an overall 42% yield based on the 1-chlorosugar, and 30% if calculated based on the sodium salt since this was used in a 2.3 molar excess.

To increase the regioselectivity towards glycosylation of the N-9 position, Gupta and Munk recently ( Gupta, P. K. and Munk, S. A., US20040039190 , WO2004018490 and CA2493724 ) conducted an SN2 reaction using the anomerically pure α-anomer, 1-chloro-2-deoxy-3,5-di-O–p-toluoyl-α-D-ribofuranose but coupling it with the potassium salt of a 6-heptanoylamido modified purine (see Scheme 5). The bulky alkyl group probably imparted steric hindrance around the N-7 position, resulting in the reported improved regioselectivity. Despite this, following deprotection, the overall yield of cladribine based on the 1-chlorosugar was 43%, showing no large improvement in overall yield on related methods. Moreover 2-chloroadenine required prior acylation with heptanoic anhydride at high temperature (130°C) in 72% yield, and the coupling required cryogenic cooling (-30°C) and the use of the strong base potassium hexamethyldisilazide and was followed by column chromatography to purify the product protected cladribine.

More recently Robins et al. (Robins, M. J. et al., J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 7773-7779, US20080207891 ) published a procedure for synthesis of cladribine that purports to achieve almost quantitative yields in the N-9-regioselective glycosylation of 6-(substituted-imidazol-1-yl)-purine sodium salts with 1-chloro-2-deoxy-3,5-di-O–p-toluoyl-α-D-ribofuranose in MeCN/dichloromethane (DCM) mixtures to give small or no detectable amounts of the undesired α-anomer (see Scheme 6). In actuality this was only demonstrated on the multi-milligram to several grams scale, and whilst the actual coupling yield following chromatography of the desired N-9-β-anomer was high (83% to quantitative), the protected 6-(substituted-imidazol-1-yl)-products were obtained in 55% to 76% yield after recrystallisation. Following this, toxic benzyl iodide was used to activate the 6-(imidazole-1-yl) groups which were then subsequently displaced by ammonia at 60-80°C in methanolic ammonia to give cladribine in 59-70% yield following ion exchange chromatography and multiple crystallisations, or following extraction with DCM and crystallisation. Although high anomeric and regioselective glycosylation was demonstrated the procedure is longer than the prior arts, atom uneconomic and not readily applicable to industrial synthesis of cladribine such as due to the reliance on chromatography and the requirement for a pressure vessel in the substitution of the 6-(substituted-imidazole-1-yl) groups.

EXAMPLE 1 Preparation of 2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine

- [0052]

2-Chloroadenine (75 g, 0.44 mol, 1.0 eq.), MeCN (900 mL, 12 P), and BSTFA (343.5 g, 1.33 mol, 3.0 eq.) were stirred and heated under reflux until the mixture was almost turned clear. The mixture was cooled to 60°C and TfOH (7.9 mL, 0.089 mol, 0.2 eq.) and then 1-O-acetyl-3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-D-ribofuranose (III; 200.6 g, 1.0 eq.) were added into the mixture, and then the mixture was stirred at 60°C. After 1 hour, some solid precipitated from the solution and the mixture was heated for at least a further 10 hours. The mixture was cooled to r.t. and stirred for 2 hours. The solid was filtered and dried in vacuo at 60°C to give 180.6 g in 64% yield of a mixture of 2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofurano syl]-purine (IVa) with 95.4% HPLC purity and its non-silylated derivative 2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2′-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine (IVb) with 1.1 % HPLC purity.

EXAMPLE 2 Preparation of 2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine by isomerisation of a mixture of 2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-α,β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine mixture

- [0053]

50.0 g of 2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-α,β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine as a 0.6:1.0 mixture of the β-anomer IVb and α-anomer Vb(83.16 mmol, assay of α-anomer was 58.6% (52.06 mmol) and β-anomer was 34.3% (31.10 mmol, 17.15 g)), 68.6 g BSTFA (266.5 mmol) and 180 mL of MeCN (3.6 P) were charged into a dried 4-necked flask. The mixture was heated to 60°C under N2 for about 3 h and then 2.67 g of TfOH (17.8 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred at 60°C for 15 h and was then cooled to about 25°C and stirred for a further 2 h, and then filtered. The filter cake was washed twice with MeCN (20 mL each) and dried at 60°C in vacuo for 6 h to give 24 g of off-white solid (the assay of 2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-α-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine was 1.4% (0.60 mmol, 0.34 g),

2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine was 8.4% (3.18 mmol, 2.02 g) and

2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine was 86.6% (32.73 mmol, 20.78 g)).

Analysis of the 274.8 g of the mother liquor by assay showed that it in addition to the α-anomer it contained 0.5% (1.37 g, 2.43 mmol) of

2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine and 0.01% (0.027 g, 0.05 mmol) of

2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine.

EXAMPLE 3 Preparation of 2-chloro-2′-deoxy-adenosine (cladribine)

- [0054]

To the above prepared mixture of 2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofurano syl]- purine (IVa) and 2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2′-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine (IVb) (179 g, >95.4% HPLC purity) in MeOH (895 mL, 5 P) was added 29% MeONa/MeOH solution (5.25 g, 0.1 eq.) at 20-30°C. The mixture was stirred at 20-30°C for 6 hours, the solid was filtered, washed with MeOH (60 mL, 0.34 P) and then dried in vacuo at 50°C for 6 hour to give 72 g white to off-white crude cladribine with 98.9% HPLC purity in ca. 93% yield.

EXAMPLE 4 Recrystallisation

- [0055]

Crude cladribine (70 g), H2O (350 mL, 5 P), MeOH (350 mL, 5 P) and 29% MeONa/MeOH solution (0.17 g) were stirred and heated under reflux until the mixture turned clear. The mixture was stirred for 3 hour and was then filtered to remove the precipitates at 74-78°C. The mixture was stirred and heated under reflux until the mixture turned clear and was then cooled. Crystals started to form at ca. 45°C. The slurry was stirred for 2 hour at the cloudy point. The slurry was cooled slowly at a rate of 5°C/0.5 hour. The slurry was stirred at 10-20°C for 4-8 hours and then filtered. The filter cake was washed three times with MeOH (50 mL each) and dried at 50°C in vacuo for 6 hours to give 62.7 g of 99.9% HPLC pure cladribine in ca. 90% yield.

EXAMPLE 5 Preparation of 2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine

- [0056]

2-Chloroadenine (2.2 Kg, 13.0 mol, 1.0 eq.), MeCN (20.7 Kg, 12 P), and BSTFA (10.0 Kg, 38.9 mol, 3.0 eq.) were stirred and heated under reflux for 3 hours and then filtered through celite and was cooled to about 60°C. TfOH (0.40 Kg, 2.6 mol, 0.2 eq.) and 1-O-acetyl-3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-D-ribofuranose (III; 5.87 Kg, 13.0 mol, 1.0 eq.) were added into the filtrate and the mixture was stirred at about 60°C for 29.5 hours. The slurry was cooled to about 20°C and stirred for 2 hours. The solids were filtered and washed with MeCN (2.8 Kg) twice and dried in vacuo at 60°C to give 5.17 Kg with a 96.5% HPLC purity in 62% yield of a mixture of 2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofurano syl]-purine (IVa), and non-silylated derivative 2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2′-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine (IVb).

EXAMPLE 6 Preparation of 2-chloro-2′-deoxy-adenosine (cladribine)

- [0057]

To a mixture of 25% sodium methoxide in MeOH (0.11 Kg, 0.5 mol, 0.1 eq.) and MeOH (14.8 Kg, 5 P) at about at 25°C was added 2-chloro-6-trimethylsilylamino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2-deoxy-β-D-ribofurano syl]-purine (IVa) and non-silylated derivative 2-chloro-6-amino-9-[3,5-di-O-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2′-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl]-purine (IVb) (3.70 Kg, combined HPLC purity of >96.3%) and the mixture was agitated at about 25°C for 2 hours. The solids were filtered, washed with MeOH (1.11 Kg, 0.4 P) and then dried in vacuo at 60°C for 4 hours to give 1.43 Kg of a crude cladribine with 97.8% HPLC purity in ca. 87% yield.

EXAMPLE 7 Recrystallisation of crude cladribine

- [0058]

A mixture of crude cladribine (1.94 Kg, >96.0% HPLC purity), MeOH (7.77 Kg, 5 P), process purified water (9.67 Kg, 5 P) and 25% sodium methoxide in MeOH (32 g, 0.15 mol) were stirred and heated under reflux until the solids dissolved. The solution was cooled to about 70°C and treated with activated carbon (0.16 Kg) and celite for 1 hour at about 70°C, rinsed with a mixture of preheated MeOH and process purified water (W/W = 1:1.25, 1.75 Kg). The filtrate was cooled to about 45°C and maintained at this temperature for 1 hours, and then cooled to about 15°C and agitated at this temperature for 2 hours. The solids were filtered and washed with MeOH (1.0 Kg, 0.7 P) three times and were then dried in vacuo at 60°C for 4 hours giving API grade cladribine (1.5 Kg, 5.2 mol) in 80% yield with 99.84% HPLC purity.

EXAMPLE 8 Recrystallisation of crude cladribine

- [0059]

A mixture of crude cladribine (1.92 Kg, >95.7% HPLC purity), MeOH (7.76 Kg, 5 P), process purified water (9.67 Kg, 5 P) and 25% sodium methoxide in MeOH (36 g, 0.17 mol) were stirred and heated under reflux until the solids dissolved. The solution was cooled to about 70°C and treated with activated carbon (0.15 Kg) and celite for 1 hour at about 70°C, rinsed with a mixture of preheated MeOH and process purified water (1:1.25, 1.74 Kg). The filtrate was cooled to about 45°C and maintained at this temperature for 1 hour, and then cooled to about 15°C and agitated at this temperature for 2 hours. The solids were filtered and washed with MeOH (1.0 Kg, 0.7 P) three times and were giving damp cladribine (1.83 Kg). A mixture of this cladribine (1.83 Kg), MeOH (7.33 Kg, 5 P) and process purified water (9.11 Kg, 5 P) were stirred and heated under reflux until the solids dissolved and was then cooled to about 45°C and maintained at this temperature for 1 hours. The slurry was further cooled to about 15°C and agitated at this temperature for 2 hours. The solids were filtered and washed with MeOH (0.9 Kg, 0.7 P) three times and were then dried in vacuo at 60°C for 4 hours giving API grade cladribine (1.38 Kg, 4.8 mol) in 75% yield with 99.86% HPLC purity.

SYN

Cladribine can be got from 2-Deoxy-D-ribose. The detail is as follows:

SYN

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15257770.2015.1071848?journalCode=lncn20

March 29, 2019

Release

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved Mavenclad (cladribine) tablets to treat relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) in adults, to include relapsing-remitting disease and active secondary progressive disease. Mavenclad is not recommended for MS patients with clinically isolated syndrome. Because of its safety profile, the use of Mavenclad is generally recommended for patients who have had an inadequate response to, or are unable to tolerate, an alternate drug indicated for the treatment of MS.

“We are committed to supporting the development of safe and effective treatments for patients with multiple sclerosis,” said Billy Dunn, M.D., director of the Division of Neurology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “The approval of Mavenclad represents an additional option for patients who have tried another treatment without success.”

MS is a chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that disrupts communications between the brain and other parts of the body. Most people experience their first symptoms of MS between the ages of 20 and 40. MS is among the most common causes of neurological disability in young adults and occurs more frequently in women than in men.

For most people, MS starts with a relapsing-remitting course, in which episodes of worsening function (relapses) are followed by recovery periods (remissions). These remissions may not be complete and may leave patients with some degree of residual disability. Many, but not all, patients with MS experience some degree of persistent disability that gradually worsens over time. In some patients, disability may progress independent of relapses, a process termed secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS). In the first few years of this process, many patients continue to experience relapses, a phase of the disease described as active SPMS. Active SPMS is one of the relapsing forms of MS, and drugs approved for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS can be used to treat active SPMS.

The efficacy of Mavenclad was shown in a clinical trial in 1,326 patients with relapsing forms of MS who had least one relapse in the previous 12 months. Mavenclad significantly decreased the number of relapses experienced by these patients compared to placebo. Mavenclad also reduced the progression of disability compared to placebo.

Mavenclad must be dispensed with a patient Medication Guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks. Mavenclad has a Boxed Warning for an increased risk of malignancy and fetal harm. Mavenclad is not to be used in patients with current malignancy. In patients with prior malignancy or with increased risk of malignancy, health care professionals should evaluate the benefits and risks of the use of Mavenclad on an individual patient basis. Health care professionals should follow standard cancer screening guidelines in patients treated with Mavenclad. The drug should not be used in pregnant women and in women and men of reproductive potential who do not plan to use effective contraception during treatment and for six months after the course of therapy because of the potential for fetal harm. Mavenclad should be stopped if the patient becomes pregnant.

Other warnings include the risk of decreased lymphocyte (white blood cell) counts; lymphocyte counts should be monitored before, during and after treatment. Mavenclad may increase the risk of infections; health care professionals should screen patients for infections and treatment with Mavenclad should be delayed if necessary. Mavenclad may cause hematologic toxicity and bone marrow suppression so health care professionals should measure a patient’s complete blood counts before, during and after therapy. The drug has been associated with graft-versus-host-disease following blood transfusions with non-irradiated blood. Mavenclad may cause liver injury and treatment should be interrupted or discontinued, as appropriate, if clinically significant liver injury is suspected.

The most common adverse reactions reported by patients receiving Mavenclad in the clinical trials include upper respiratory tract infections, headache and decreased lymphocyte counts.

The FDA granted approval of Mavenclad to EMD Serono, Inc.

References

- ^ Drugs.com International trade names for Cladribine Page accessed Jan 14, 2015

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “PRODUCT INFORMATION LITAK© 2 mg/mL solution for injection” (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. St Leonards, Australia: Orphan Australia Pty. Ltd. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ Liliemark, Jan (1997). “The Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Cladribine”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 32 (2): 120–131. doi:10.2165/00003088-199732020-00003. PMID 9068927.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “European Medicines Agency – – Litak”. www.ema.europa.eu.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Leustat Injection. – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) – (eMC)”. www.medicines.org.uk.

- ^ Leist, TP; Weissert, R (2010). “Cladribine: mode of action and implications for treatment of multiple sclerosis”. Clinical Neuropharmacology. 34 (1): 28–35. doi:10.1097/wnf.0b013e318204cd90. PMID 21242742.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Cladribine label, last updated July 2012. Page accessed January 14, 2015

- ^ https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm634837.htm

- ^ Histiocytosis Association Erdheim-Chester Disease Page accessed Aug 20, 2016

- ^ Aricò M (2016). “Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: from the bench to bedside for an updated therapy”. Br J Haematol. 173 (5): 663–70. doi:10.1111/bjh.13955. PMID 26913480.

The combination of cytarabine and cladribine is the current standard for second-line therapy of refractory cases with vital organ dysfunction.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Giovannoni, G; Comi, G; Cook, S; Rammohan, K; Rieckmann, P; Soelberg Sørensen, P; Vermersch, P; Chang, P; Hamlett, A; Musch, B; Greenberg, SJ; CLARITY Study, Group. (4 February 2010). “A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (5): 416–26. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0902533. PMID 20089960.

- ^ Johnston, JB (June 2011). “Mechanism of action of pentostatin and cladribine in hairy cell leukemia”. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 52 Suppl 2: 43–5. doi:10.3109/10428194.2011.570394. PMID 21463108.

- ^ Beutler, E; Piro, LD; Saven, A; Kay, AC; McMillan, R; Longmire, R; Carrera, CJ; Morin, P; Carson, DA (1991). “2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine (2-CdA): A Potent Chemotherapeutic and Immunosuppressive Nucleoside”. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 5 (1): 1–8. doi:10.3109/10428199109068099. PMID 27463204.

- ^ Baker, D; Marta, M; Pryce, G; Giovannoni, G; Schmierer, K (February 2017). “Memory B Cells are Major Targets for Effective Immunotherapy in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis”. EBioMedicine. 16: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.01.042. PMC 5474520. PMID 28161400.

- ^ Baker, D; Herrod, SS; Alvarez-Gonzalez, C; Zalewski, L; Albor, C; Schmierer, K (July 2017). “Both cladribine and alemtuzumab may effect MS via B-cell depletion”. Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation. 4 (4): e360. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000360. PMC 5459792. PMID 28626781.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ceronie, B; Jacobs, BM; Baker, D; Dubuisson, N; Mao, Z; Ammoscato, F; Lock, H; Longhurst, HJ; Giovannoni, G; Schmierer, K (May 2018). “Cladribine treatment of multiple sclerosis is associated with depletion of memory B cells”. Journal of Neurology. 265 (5): 1199–1209. doi:10.1007/s00415-018-8830-y. PMC 5937883. PMID 29550884.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Marshall A. Lichtman Biographical Memoir: Ernest Beutler 1928–2008 National Academy of Sciences, 2012

- ^ Staff, The Pink Sheet Mar 8, 1993 Ortho Biotech’s Leustatin For Hairy Cell Leukemia

- ^ Jump up to:a b EMA 2004 Litak EMA package: Scientific Discussion

- ^ EMA 2004 Litak: Background Information one the Procedure

- ^ Eric Sauter and Mika Ono for Scripps News and Views. Vol 9. Issue 18. June 1, 2009 A Potential New MS Treatment’s Long and Winding Road

- ^ Tortorella C, Rovaris M, Filippi M (2001). “Cladribine. Ortho Biotech Inc”. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2 (12): 1751–6. PMID 11892941.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Carey Sargent for Dow Jones Newswires in the Wall Street Journal. Oct. 31, 2002 Serono Purchases Rights To Experimental MS Drug

- ^ Reuters. Dec 4, 2000. Ivax to Develop Cladribine for Multiple Sclerosis

- ^ Jennifer Bayot for the New York Times. July 26, 2005 Teva to Acquire Ivax, Another Maker of Generic Drugs

- ^ Teva Press Release, 2006. Teva Completes Acquisition of Ivax

- ^ Staff, First Word Pharma. Sept 21, 2006 Merck KGaA to acquire Serono

- ^ Jump up to:a b c EMA. 2011 Withdrawal Assessment Report for Movectro Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/001197

- ^ Jump up to:a b John Gever for MedPage Today June 22, 2011 06.22.2011 0 Merck KGaA Throws in Towel on Cladribine for MS

- ^ Jump up to:a b John Carroll for FierceBiotech Sep 11, 2015 Four years after a transatlantic slapdown, Merck KGaA will once again seek cladribine OK

- ^ Connolly, Allison (24 April 2012). “Merck KGaA to Close Merck Serono Site in Geneva, Cut Jobs”. Bloomberg.

- ^ Pakpoor, J; et al. (December 2015). “No evidence for higher risk of cancer in patients with multiple sclerosis taking cladribine”. Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation. 2 (6): e158. doi:10.1212/nxi.0000000000000158. PMC 4592538. PMID 26468472.

- ^ Press release

- ^ Merck. “Cladribine Tablets Receives Positive CHMP Opinion for Treatment of Relapsing Forms of Multiple Sclerosis”. www.prnewswire.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-08-22.

- ^ Cladribine approved in Europe, Press Release

- ^ Jump up to:a b Giovannoni, G; Soelberg Sorensen, P; Cook, S; Rammohan, K; Rieckmann, P; Comi, G; Dangond, F; Adeniji, AK; Vermersch, P (1 August 2017). “Safety and efficacy of cladribine tablets in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Results from the randomized extension trial of the CLARITY study”. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England): 1352458517727603. doi:10.1177/1352458517727603. PMID 28870107.

- ^ “Sustained Efficacy – Merck Neurology”. Merck Neurology. Retrieved 28 September2018.

- ^ Guarnera, C; Bramanti, P; Mazzon, E (2017). “Alemtuzumab: a review of efficacy and risks in the treatment of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis”. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 13: 871–879. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S134398. PMC 5522829. PMID 28761351.

- ^ Baker, D; Herrod, SS; Alvarez-Gonzalez, C; Giovannoni, G; Schmierer, K (1 August 2017). “Interpreting Lymphocyte Reconstitution Data From the Pivotal Phase 3 Trials of Alemtuzumab”. JAMA Neurology. 74 (8): 961–969. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0676. PMC 5710323. PMID 28604916.

- ^ “Cladribine tablets for treating relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis”. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Hasanali, Zainul S.; Saroya, Bikramajit Singh; Stuart, August; Shimko, Sara; Evans, Juanita; Shah, Mithun Vinod; Sharma, Kamal; Leshchenko, Violetta V.; Parekh, Samir (24 June 2015). “Epigenetic therapy overcomes treatment resistance in T cell prolymphocytic leukemia”. Science Translational Medicine. 7 (293): 293ra102. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5079. ISSN 1946-6234. PMC 4807901. PMID 26109102.

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Leustatin, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a693015 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

Intravenous, subcutaneous(liquid) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (i.v.); 37 to 51% (orally)[3] |

| Protein binding | 25% (range 5-50%)[2] |

| Metabolism | Mostly via intracellularkinases; 15-18% is excreted unchanged[2] |

| Elimination half-life | Terminal elimination half-life: Approximately 10 hours after both intravenous infusion an subcutaneous bolus injection[2] |

| Excretion | Urinary[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChemCID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.726 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H12ClN5O3 |

| Molar mass | 285.687 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |