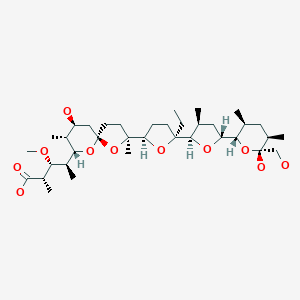

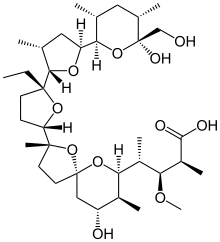

モネンシン;

MONENSIN

- Molecular FormulaC36H62O11

- Average mass670.871 Da

Monensin is a polyether antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces cinnamonensis.[1] It is widely used in ruminant animal feeds.[1][2]

The structure of monensin was first described by Agtarap et al. in 1967, and was the first polyether antibiotic to have its structure elucidated in this way. The first total synthesis of monensin was reported in 1979 by Kishi et al.[3]

SYN

SYN

https://www.chemie.tu-darmstadt.de/media/ak_fessner/damocles_pdf/2017/Monensin.pdf

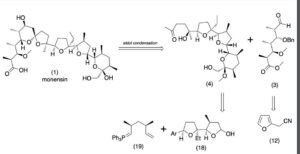

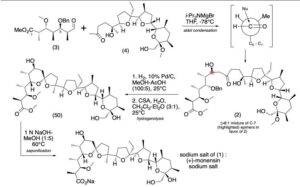

Production / synthesis Monensin is produced in vivo by Streptomyces cinnamonensis as a natural defense against competing bacteria. Monensin presents a formidable challenge to synthetic chemists as it possesses 17 asymmetric centers on a backbone of only 26 carbon atoms. Although its total synthesis has been described (e.g., Kishi et al., 1979), the high complexity of monensin makes an extraction from the bacterium the most economical procedure for its production. The total synthesis has 56 steps and a yield of only 0.26%. The chemical precursors are 2-allyl-1,3-propanediol and 2- (furan-2-yl)acetonitrile. The method used for synthesizing monensin is based on the principle of “absolute asymmetric synthesis”. Molecules are constructed out of prefabricated building blocks in the correct conformation, aiming for higher yields of the desired enantiomer. New stereocenters are also introduced. Using this method, monensin is assembled in two parts, a larger right side and a smaller left one. The penultimate step is connecting the left and the right halves of monensin, which are independently generated, in an Aldol-condensation. The two halves’ keto end groups (C7/ C8) are linked by eliminating a water molecule. The C7 atom is favored over the C1 atom, because it is more reactive. For catalyzing this step, Yoshito Kishi’s group used iPr2NMgBr (Hauser base) and THF to coordinate it at a temperature of − 78°C. Thus, they were able to isolate the molecule in the right conformation at a ratio of 8:1. Due to the low temperature required for a high yield of the correct enantiomer, the reaction is very solw. One of the most difficult steps is the last one: the connection of the spiro center. This is due to a characteristic feature of spiro compounds; they open and close very easily. Therefore, the conditions for forming the right conformation must be optimal in the last step of synthesis. The biosynthesis in a cell culture of Streptomyces cinnamonensis involves a complex medium containing, among other components, glucose, soybean oil, and grit. Cultivation is carried out for a week at a temperature of 30°C and under constant aeration. Product isolation requires filtration, acidification to pH3, extraction with chloroform and purification with activated carbon. In this way, a few grams per liter of monensin are produced and isolated. For crystallization, azeotropic distillation is necessary. In vivo, polyether backbones are assembled by modular polyketide synthases and are modified by two key enzymes, epoxidase and epoxide hydrolase, to generate the product. Precursors of the polyketide pathway are acetate, butyrate and propionate.

SYN

The final-stage aldol addition in Yoshito Kishi‘s 1979 total synthesis of monensin. (1979). “Synthetic studies on polyether antibiotics. 6. Total synthesis of monensin. 3. Stereocontrolled total synthesis of monensin”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101 (1): 262–263. DOI:10.1021/ja00495a066.

SYN

https://www2.chemistry.msu.edu/courses/cem852/classics/Chapter12.pdf

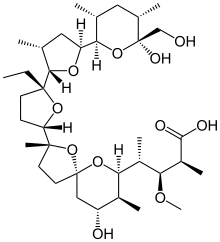

A polyether antibiotic, Monensin was the first member of this class of molecules to be structurally characterized.1 The structural features of these polyethers comprise of a terminal carboxylic acid, multiple cyclic ether rings (ex. Tetrahydrofuran and tetrahydropyran), a large amount of stereocenters and (for many of these molecules) one or more spiroketal moieties.2 Monensin was introduced into the market in 1971 and is used to fight coccidial infections in poultry and as an additive in cattle feed.3 Of the 26 carbon atom’s in Monensin’s backbone, 17 are stereogenic and six of those are contiguous. Coupled with a spiroketal moiety, three hydrofuran rings and two hydropyran rings, the molecule was an attractive synthetic target.

1. Agtarap, A.; Chamberlain, J.W.; Pinkerton, M.; Stein-rauf, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 5737 2. Polyether Antibiotics : Naturally Occurring Acid Ionophores. Westley J.W.; Marcel Dekker: New York (1982) Vol. 1-2. 3. Stark, W.M. In Fermentation Advances, Perlman, D., Ed., Academic Press: New York, 1969, 517

Retrosynthetic Analysis of Monensin

//////////

AS ON DEC2021 3,491,869 VIEWS ON BLOG WORLDREACH AVAILABLEFOR YOUR ADVERTISEMENT

join me on Linkedin

Anthony Melvin Crasto Ph.D – India | LinkedIn

join me on Researchgate

RESEARCHGATE

join me on Facebook

Anthony Melvin Crasto Dr. | Facebook

join me on twitter

Anthony Melvin Crasto Dr. | twitter

+919321316780 call whatsaapp

EMAIL. amcrasto@amcrasto

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Mechanism of action

Monensin A is an ionophore related to the crown ethers with a preference to form complexes with monovalent cations such as: Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, Ag+, and Tl+.[4][5] Monensin A is able to transport these cations across lipid membranes of cells in an electroneutral (i.e. non-depolarizing) exchange, playing an important role as an Na+/H+ antiporter. Recent studies have shown that monensin may transport sodium ion through the membrane in both electrogenic and electroneutral manner.[6] This approach explains ionophoric ability and in consequence antibacterial properties of not only parental monensin, but also its derivatives that do not possess carboxylic groups. It blocks intracellular protein transport, and exhibits antibiotic, antimalarial, and other biological activities.[7] The antibacterial properties of monensin and its derivatives are a result of their ability to transport metal cations through cellular and subcellular membranes.[8]

Uses

Monensin is used extensively in the beef and dairy industries to prevent coccidiosis, increase the production of propionic acid and prevent bloat.[9] Furthermore, monensin, but also its derivatives monensin methyl ester (MME), and particularly monensin decyl ester (MDE) are widely used in ion-selective electrodes.[10][11][12]

In laboratory research, monensin is used extensively to block Golgi transport.[13][14][15]

Toxicity

Monensin has some degree of activity on mammalian cells and thus toxicity is common. This is especially pronounced in horses, where monensin has a median lethal dose 1/100th that of ruminants. Accidental poisoning of equines with monensin is a well-documented occurrence which has resulted in deaths.[16]

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b Daniel Łowicki and Adam Huczyński (2013). “Structure and Antimicrobial Properties of Monensin A and Its Derivatives: Summary of the Achievements”. BioMed Research International. 2013: 1–14. doi:10.1155/2013/742149. PMC 3586448. PMID 23509771.

- ^ Butaye, P.; Devriese, L. A.; Haesebrouck, F. (2003). “Antimicrobial Growth Promoters Used in Animal Feed: Effects of Less Well Known Antibiotics on Gram-Positive Bacteria”. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 16 (2): 175–188. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.2.175-188.2003. PMC 153145. PMID 12692092.

- ^ Nicolaou, K. C.; E. J. Sorensen (1996). Classics in Total Synthesis. Weinheim, Germany: VCH. pp. 185–187. ISBN 3-527-29284-5.

- ^ Huczyński, A.; Ratajczak-Sitarz, M.; Katrusiak, A.; Brzezinski, B. (2007). “Molecular structure of the 1:1 inclusion complex of Monensin A lithium salt with acetonitrile”. J. Mol. Struct. 871 (1–3): 92–97. Bibcode:2007JMoSt.871…92H. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2006.07.046.

- ^ Pinkerton, M.; Steinrauf, L. K. (1970). “Molecular structure of monovalent metal cation complexes of monensin”. J. Mol. Biol. 49 (3): 533–546. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(70)90279-2. PMID 5453344.

- ^ Huczyński, Adam; Jan Janczak; Daniel Łowicki; Bogumil Brzezinski (2012). “Monensin A acid complexes as a model of electrogenic transport of sodium cation”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1818 (9): 2108–2119. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.04.017. PMID 22564680.

- ^ Mollenhauer, H. H.; Morre, D. J.; Rowe, L. D. (1990). “Alteration of intracellular traffic by monensin; mechanism, specificity and relationship to toxicity”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1031 (2): 225–246. doi:10.1016/0304-4157(90)90008-Z. PMC 7148783. PMID 2160275.

- ^ Huczyński, A.; Stefańska, J.; Przybylski, P.; Brzezinski, B.; Bartl, F. (2008). “Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of Monensin A esters”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18 (8): 2585–2589. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.03.038. PMID 18375122.

- ^ Matsuoka, T.; Novilla, M.N.; Thomson, T.D.; Donoho, A.L. (1996). “Review of monensin toxicosis in horses”. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 16: 8–15. doi:10.1016/S0737-0806(96)80059-1.

- ^ Tohda, Koji; Suzuki, Koji; Kosuge, Nobutaka; Nagashima, Hitoshi; Watanabe, Kazuhiko; Inoue, Hidenari; Shirai, Tsuneo (1990). “A sodium ion selective electrode based on a highly lipophilic monensin derivative and its application to the measurement of sodium ion concentrations in serum”. Analytical Sciences. 6 (2): 227–232. doi:10.2116/analsci.6.227.

- ^ Kim, N.; Park, K.; Park, I.; Cho, Y.; Bae, Y. (2005). “Application of a taste evaluation system to the monitoring of Kimchi fermentation”. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 20 (11): 2283–2291. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2004.10.007. PMID 15797327.

- ^ Toko, K. (2000). “Taste Sensor”. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 64 (1–3): 205–215. doi:10.1016/S0925-4005(99)00508-0.

- ^ Griffiths, G.; Quinn, P.; Warren, G. (March 1983). “Dissection of the Golgi complex. I. Monensin inhibits the transport of viral membrane proteins from medial to trans Golgi cisternae in baby hamster kidney cells infected with Semliki Forest virus”. The Journal of Cell Biology. 96 (3): 835–850. doi:10.1083/jcb.96.3.835. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2112386. PMID 6682112.

- ^ Kallen, K. J.; Quinn, P.; Allan, D. (1993-02-24). “Monensin inhibits synthesis of plasma membrane sphingomyelin by blocking transport of ceramide through the Golgi: evidence for two sites of sphingomyelin synthesis in BHK cells”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 1166 (2–3): 305–308. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(93)90111-l. ISSN 0006-3002. PMID 8443249.

- ^ Zhang, G. F.; Driouich, A.; Staehelin, L. A. (December 1996). “Monensin-induced redistribution of enzymes and products from Golgi stacks to swollen vesicles in plant cells”. European Journal of Cell Biology. 71 (4): 332–340. ISSN 0171-9335. PMID 8980903.

- ^ “Tainted feed blamed for 4 horse deaths at Florida stable”. 2014-12-16.

|

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(2S,3R,4S)-4-[(2S,5R,7S,8R,9S)-2-{(2S,2′R,3′S,5R,5′R)-2-Ethyl-5′-[(2S,3S,5R,6R)-6-hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-3,5-dimethyloxan-2-yl]-3′-methyl[2,2′-bioxolan]-5-yl}-9-hydroxy-2,8-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[4.5]decan-7-yl]-3-methoxy-2-methylpentanoic acid

|

|

| Other names

Monensic acid

|

|

| Identifiers | |

|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.037.398 |

| E number | E714 (antibiotics) |

| KEGG | |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C36H62O11 | |

| Molar mass | 670.871 g/mol |

| Appearance | solid state, white crystals |

| Melting point | 104 °C (219 °F; 377 K) |

| 3×10−6 g/dm3 (20 °C) | |

| Solubility | ethanol, acetone, diethyl ether, benzene |

| Pharmacology | |

| QA16QA06 (WHO) QP51AH03 (WHO) | |

| Related compounds | |

|

Related

|

antibiotics, ionophores |

|

Related compounds

|

Monensin A methyl ester, |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

|

|

///////////MONENSIN, Elancoban, VETERINARY, Coccidiostat, A-3823A, A 3823A