RITONAVIR

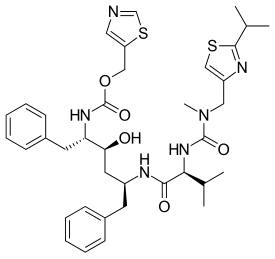

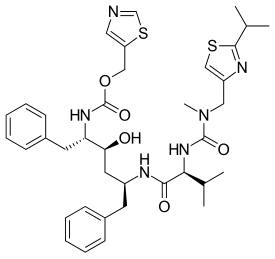

- Molecular FormulaC37H48N6O5S2

- Average mass720.944 Da

- A-84538

- Abbott 84538

- ABBOTT-84538

- ABT 538

- ABT-538

- DRG-0244

- NSC-693184

- TMC 114r

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-02-10 | New dosage form | Norvir | HIV infection | Tablet | 100 mg | Abbvie | |

| 1999-06-29 | Additional approval | Norvir | HIV infection | Capsule | 100 mg | Abbvie | |

| 1996-03-01 | New dosage form | Norvir | HIV infection | Capsule | 100 mg | Abbvie | Priority |

| 1996-03-01 | First approval | Norvir | HIV infection | Solution | 80 mg/mL | Abbvie |

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996-08-26 | First approval | Norvir | HIV infection | Capsule | 100 mg | Abbvie | |

| 1996-08-26 | First approval | Norvir | HIV infection | Tablet, Film coated | 100 mg | Abbvie | |

| 1996-08-26 | First approval | Norvir | HIV infection | Solution | 80 mg/mL | Abbvie |

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-02-28 | New dosage form | Norvir | HIV infection | Tablet | 100 mg | Abbvie | |

| 1998-09-25 | First approval | Norvir | HIV infection | Solution | 80 mg/mL | Abbvie |

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013-10-15 | Marketing approval | HIV infection | Tablet | 100 mg | Abbvie | ||

| 2010-07-29 | Marketing approval | 爱治威/Norvir | HIV infection | Capsule | 100 mg | Abbott | |

| 2010-07-13 | Marketing approval | 迈可欣 | HIV infection | Solution | 75 ml:6 g | 美吉斯制药(厦门) | 3.1类 |

Ritonavir was first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on March 1, 1996, then approved by European Medicine Agency (EMA) on August 26, 1996, and approved by Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency of Japan (PMDA) on September 25, 1998. It was developed and marketed as Norvir® by Abbvie.

Ritonavir is an HIV protease inhibitor. It is indicated in combination with other antiretroviral agents for the treatment of HIV-1 infection.

Norvir® is available as solution for oral use, containing 80 mg of free Ritonavir per mL. The recommended dose is 600 mg twice-day with meals for adult patients.

Ritonavir (RTV), sold under the brand name Norvir, is an antiretroviral medication used along with other medications to treat HIV/AIDS.[2] This combination treatment is known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).[2] Often a low dose is used with other protease inhibitors.[2] It may also be used in combination with other medications for hepatitis C.[3] It is taken by mouth.[2] The capsules of the medication do not work the same as the tablets.[2]

Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and numbness of the hands and feet.[2] Serious side effects include liver problems, pancreatitis, allergic reactions, and arrythmias.[2] Serious interactions may occur with a number of other medications including amiodarone and simvastatin.[2] At low doses it is considered to be acceptable for use during pregnancy.[4] Ritonavir is of the protease inhibitor class.[2] Typically, however, it is used to inhibit the enzyme that metabolizes other protease inhibitors.[5] This inhibition allows lower doses of these latter medication to be used.[5]

Ritonavir was patented in 1989 and came into medical use in 1996.[6][7] It is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines.[8] Ritonavir capsules were approved as a generic medication in the United States in 2020.[9]

join me on Linkedin

Anthony Melvin Crasto Ph.D – India | LinkedIn

join me on Researchgate

RESEARCHGATE

join me on Facebook

Anthony Melvin Crasto Dr. | Facebook

join me on twitter

Anthony Melvin Crasto Dr. | twitter

+919321316780 call whatsaapp

EMAIL. amcrasto@amcrasto

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

SYN

https://www.scielo.br/j/mioc/a/FT4WXwhbCPCkm7W6XdX4GHm/?lang=en

Ritonavir (2) – The first disclosure of ritonavir (2) is presented in a patent from 1994, assigned to Abbott Laboratories. Even though the patent consists of a range of Markush structures, among which is found (2), its synthesis is not presented.249 The synthetic pathway to obtain (2) was disclosed for the first time in a second-generation patent in 1995, by the same company.250,251 Some drawbacks related to the synthesis presented by Abbott include the employment of expensive condensing agents, as 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and poor reaction yields on the first steps of the synthetic pathway, making this strategy too expensive and not suitable for scale-up production. Considering the above deficiencies, a recent Chinese patent concerning the synthesis of ritonavir (2) has been released.

The synthetic pathway described in the patent starts with a nucleophilic addition-elimination reaction between the starting material (2-isopropylthiazol-4-yl)- nitro-methylamine (71) and N-[(2,2,2-trichloroethoxy)carbonyl]-L-valine (72), generating intermediate (73). The intermediate is mixed with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride and triethylamine to activate the acid function, followed by the addition of reagent (74) in a one-pot procedure. The condensation allows the formation of intermediate (75), which is submitted to acidic conditions for a Boc deprotection, followed by another nucleophilic addition-elimination reaction with reagent (76), thus obtaining the final product ritonavir (2) (Fig. 16).252 When comparing both patents, it is possible to highlight important advantages present in the latest one, including the use of cheap and easily available reagents, for instance, the use of p-toluenesulfonyl chloride as an amide condensing agent, the synthetic pathway has a high yield (79% overall), low cost and it is ease to scale-up the production.

SYN

In the first step shown, an aldehyde derived from phenylalanine is treated with zinc dust in the presence of vanadium(III) chloride. This results in a pinacol coupling reaction which dimerises the material to provide an intermediate which is converted to its epoxide and then reduced to (2S,3S,5S)-2,5-diamino-1,6-diphenylhexan-3-ol. Importantly, this retains the absolute stereochemistry of the amino acid precursor. The diamine is then treated sequentially with two thiazole derivatives, each linked by an amide bond, to provide ritonavir.[23][24]

REF 23, 24BELOW

- WO patent 1994014436, Kempf, Dale J.; Norbeck, Daniel W.; Sham, Hing Leung; Zhao, Chen; Sowin, Thomas J.; Reno, Daniel S.; Haight, Anthony R. and Cooper, Arthur J., “Retroviral protease inhibiting compounds”, published 1994-07-07, assigned to Abbott Laboratories

- ^ Vardanyan, Ruben; Hruby, Victor (2016). “34: Antiviral Drugs”. Synthesis of Best-Seller Drugs. pp. 698–701. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-411492-0.00034-1. ISBN 9780124114920. S2CID 75449475.

SYN

| EP 0674513; EP 0727419; JP 1996505844; JP 1997118679; JP 1998087639; WO 9414436 |

The oxidation of N-(benzyloxycarbonyl)-L-phenylalaninol (I) with oxalyl chloride in DMSO gives the corresponding aldehyde (II), which by dimerization with Zn dust in dichloromethane yields (2S,3R,4R,5S)-2,5-bis(benzyloxycarbonylamino)-1,6-diphenylhexane-3,4-diol (III) [along with the (2S,3S,4S,5S)-isomer]. The reaction of (III) with alpha-acetoxyisobutyryl bromide (IV) in hexane/dichloromethane affords (2S,3R,4R,5S)-2,5-bis(benzyloxycarbonylamino)-4-bromo-1,6-diphenylhexan-3-ol acetate ester (V), which is converted into the corresponding epoxide (VI) with NaOH in dioxane/water. The reduction of the epoxide (VI) with NaBH4 in THF affords (2S,3S,5S)-2,5-bis(benzyloxycarbonylamino)-1,6-diphenylhexan-3-ol (VII), which is deprotected with Ba(OH)2 in refluxing dioxane/water yielding the corresponding diamine (VIII). The cyclization of (VIII) with phenylboronic acid (IX) in refluxing toluene gives (4S,6S)-6-[1(S)-amino-2-phenylethyl]-4-benzyl-2-phenyl-1,3,2-oxaazaborinane (X), which is condensed with (5-thiazolylmethyl)(4-nitrophenyl)carbonate (XI) in THF to afford (2S,3S,5S)-5-amino-1,6-diphenyl-2-(5-thiazolylmethoxycarbonylamino) hexan-3-ol (XII). Finally, this compound is condensed with N-[N-(2-isopropylthiazol-4-ylmethyl)-N-methylaminocarbonyl]-L-valine (XIII) by means of 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HBT) and N-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-N’-ethylcarbodiimide (DEC) in THF.

SYN

The thiazolyl carbonate (XI) has been synthesized as follows: The reaction of formamide (XIV) with P2S5 in ethyl ether gives thioformamide (XV), which is cyclized with 2-chloro-3-oxopropionic acid ethyl ester (XVI) [obtained by condensation of ethyl chloroacetate (XVII) with ethyl formate (XVIII) by means of t-BuOK in THF] yielding thiazol-5-carboxylic acid ethyl ester (XIX). The reduction of (XIX) with LiAlH4 in THF affords 5-thiazolylmethanol (XX), which is then esterified with 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate (XXI) by means of 4-methylmorpholine (MPH) in dichloromethane to give the desired product (XI).

SYN

The N-substituted valine (XIII) has been synthesized as follows: The reaction of isobutyramide (XXII) with phosphorus pentasulfide (P4S10) in ethyl ether gives the corresponding thioamide (XXIII), which is cyclized with 1,3-dichloroacetone (XXIV) by means of MgSO4 in refluxing acetone yielding 4-(chloromethyl)-2-isopropylthiazole (XXV). The reaction of (XXV) with methylamine in water affords N-(2-isopropylthiazol-4-ylmethyl)-N-methylamine (XXVI), which is condensed with N-(4-nitrophenoxycarbonyl)-L-valine methyl ester (XXVII) by means of 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) and triethylamine in refluxing THF to give the thiazol-substituted L-valine ester (XXVIII). Finally, this compound is converted into the corresponding free acid with LiOH in dioxane/water. The N-(4-nitrophenoxycarbonyl)-L-valine methyl ester (XXVII) has been synthesized by reaction of chloroformate (XXI) with L-valine methyl ester (XXIX) by means of 4-methylmorpholine (MPH) in dichloromethane.

SYN

| Org Process Res Dev 1999,3(2),94 |

A new method for the preparation of a key diaminoalcohol intermediate in the synthesis of ritonavir has been described: The reaction of L-phenylalanine (XXIX) with benzyl chloride by means of K2CO3 and KOH in hot water gives N,N-dibenzyl-L-phenylalanine benzyl ester (XXX), which is condensed first with acetonitrile by means of NaNH2 and then with benzylmagnesium chloride, both reactions in methyl tert-butyl ether, yielding 5-amino-2-(dibenzylamino)-1,6-diphenylhex-4-en-3-one (XXXI). The reduction of (XXXI) with NaBH4 with an accurate control of the solvent and acidity, results in an enhanced enantioselectivity towards the desired (S,S,S)-enantiomer of 5-amino-2-(dibenzylamino)-1,6-diphenyl-3-hexanol (XXXII). Finally, this compound is deprotected by hydrogenation with ammonium formate over Pd/C in methanol/water to provide the target chiral diaminoalcohol (VIII).

SYN

| Chem Commun (London) 2001,(2),203 |

he reaction of N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-L-phenylalanine methyl ester (I) with trimethylphosphonate lithium salt (II) in THF gives the dimethyl L-phenylalanylmethylphosphonate (III), which is condensed with 2-phenylacetaldehyde (IV) by means of Na2CO3 in ethanol yielding the diphenylhexenone (V). The reduction of the carbonyl group of (V) with NaBH4 in methanol affords a diastereomeric mixture of alcohols (VI) and (VII) from which the desired major isomer (VII) is separated by column chromatography.. The epoxidation of the double bond of (VII) with MCPBA in dichloromethane gives the epoxide (VIII) (1), which is cleaved with Red-Al in THF providing the diol (IX). The reaction of (IX) with Ms-Cl and DIEA yields the intermediate dimesylate (X) which, without isolation, affords oxazolidinone (XI). The reaction of (XI) with sodium azide and 18-C-6 in DMSO gives the azide (XII), which is treated with NaH and Boc2O in THF in order to cleave the oxazolidine ring and furnish the protected aminoalcohol (XIII). Finally the azido group of (XIII) is hydrogenate with H2 over Pd/C in methanol to afford the monoprotected diaminoalcohol (XIV) the target compound.

SYN

US5543551

1. Org. Process Res. Dev. 1999, 3, 94-100.

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/op9802071

Patent

2. WO2006090264A1.

3. WO2006090270A1.

SYN

Synthesis ReferenceUS5484801

SYN

Method of synthesis

i. Valine condensed with bis-trichloromethyl carbonate to give an intermediate compound 4-isopropyloxazolidine-2,5-dione.

ii. The intermediate compound is reacted with compound (1) to give compound (2).

ii. (2) reacts with bis-trichloromethyl carbonate followed by reaction with (2-isopropylthiazol-4-yl)-N-methylmethanamine to give compound (3).

iv. Primary amine group of (3) is subjected to deprotection by the removal of two benzyl groups to give compound (4).

v. (4) reacts with (5) to give Ritonavir in good yield.

CLIP

SYN

US5543551

SYN

Ruben Vardanyan, Victor Hruby, in Synthesis of Best-Seller Drugs, 2016

Lopinavir–Kaletra

The first report of a new protease inhibitor candidate lopinavir (34.1.21) seems to be Abbott’s patent [134].

The core of lopinavir is identical to that of ritonavir. The 5-thiazolyl end group in ritonavir was replaced by the phenoxyacetyl group, and the 2-isopropylthiazolyl group in ritonavir was replaced by a modified valine in which the amino terminus had a six-membered cyclic urea attached.

Synthetic strategy employed for the synthesis of multikilogram quantities of lopinavir is very similar to that implemented for ritonavir (34.1.22), but using the protected version (34.1.79) of the “core” diamino alcohol (34.1.55), which was sequentially acylated with the acid chlorides of (S)-3-methyl-2-(2-oxotetrahydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)butanoic acid (34.1.89) and 2-(2,6-dimethylphenoxy)acetic acid (34.1.94) [135,136].

The bulk synthesis of protected diamino alcohol (34.1.79) was proposed [137,138] by a method closely related to the method [122,123] for ritonavir. For that purpose L-phenylalanine (34.1.74) was sequentially trialkylated with benzyl chloride using a K2CO3/water system at reflux to produce a tribenzylated product (34.1.75). A solution with generated acetonitrile anion in THF was added to the benzylated product (34.1.75) at less than −40°C to yield the cyanomethylketone (34.1.76), which was exposed to Grignard reagent–benzyl magnesium chloride to produce an enaminone (34.1.77). No racemization was observed in these two steps. The addition of the obtained enaminone (34.1.77) in THF/PrOH to a solution of NaBH4 and MsOH in THF at 5°C produced an intermediate aminoketone (34.1.78). No further reduction of the keto group occurs under these conditions. Reduction of the keto group could proceed by addition of a preformed solution of sodium tris(trifluoroacetoxy)borohydride in tetrahydrofuran [NaBH3(OTFA)], which produces a mixture of amino alcohols composed of 93% of the desired (2S)-5-amino-2-(dibenzylamino)-1,6-diphenylhexan-3-ol (34.1.79) along with 7% of the three undesired diastereomers. The crude mixture was debenzylated (Pd-C, HCONH4), and the product was purified by precipitation from iPrOH/HCl (aq) to produce (34.1.55) in greater than 99% purity and in high yield (Scheme 34.8.).

Scheme 34.8. The synthesis of (2S)-5-amino-2-(dibenzylamino)-1,6-diphenylhexan-3-ol.

An efficient synthesis of each of the side chain moieties and their coupling with the “core” diamino alcohol derivatives was developed as follows: (S)-3-methyl-2-(2-oxotetrahydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)butanoic acid (34.1.85) was prepared starting from L-valine (34.1.80), which was first converted to N-phenoxycarbonyl-L-valine (34.1.82) with phenylchloroformate (34.1.81). Accurate pH monitoring (pH 9.5 to 10.2) was necessary and LiOH was found to be a superior base. Control of pH was essential as the valine dimer and its derivatives were formed as reaction byproducts outside of this pH margin. LiCl was added to provide a lower freezing point to the aqueous solution and neutral Al2O3 was added to prevent gumming and emulsion formation during the course of the reaction.

Treatment of N-phenoxycarbonyl-L-valine (34.1.82) with 3-chloropropylamine hydrochloride (34.1.3) and solid NaOH in THF produced the unisolated salt of chloropropylurea (34.1.84), which was then treated with t-BuOK, effecting cyclization to produce the desired acid (34.1.85) in 75 to 85% yield and in greater than 99% enantiomeric excess. Acylation of (34.1.79) with synthesized acid (34.1.85) was initially achieved by well-known peptide coupling methods. Optimization of this transformation allowed the discovery of a more cost-effective method for implementing acyl chloride (34.1.86), which was easily prepared using thionyl chloride in THF at room temperature.

The reaction of dibenzylamino alcohols (34.1.79) with acyl chloride (34.1.86) in the presence of 3.0 equivalents of imidazole in EtOAc and DMF produced acylated intermediate (34.1.87) as a mixture of diastereomers, which, without any further purification, was subjected to debenzylation with Pd/C and HCO2NH4 in MeOH at 50°C, which proceeded without significant complications to produce (34.1.88).

Exposure of crude (34.1.88) to L-pyroglutamic acid (34.1.89) in dioxane at 50°C followed by cooling, allowed for the isolation of (S)-N-((2S,4S,5S)-5-amino-4-hydroxy-1,6-diphenylhexan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2-(2-oxotetrahydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)butanamide (34.1.90) pyroglutamic salt as virtually a single diastereomer in high yield (Scheme 34.9.).

Scheme 34.9. The synthesis of (S)-N-((2S,4S,5S)-5-amino-4-hydroxy-1,6-diphenylhexan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2-(2-oxotetrahydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)butanamide.

Acyl chloride (34.1.92) was prepared by the reaction of 2-(2,6-dimethylphenoxy)acetic acid (34.1.91) with thionyl chloride in EtOAc, at room temperature adding a single drop of DMF, and warming the slurry to 50°C, which produced a clear solution of (34.1.92) that was used in the subsequent acylation of amine (34.1.90). Reaction of pyroglutamate salt (34.1.90) with acyl chloride (34.1.95) in ethyl acetate under Schotten-Baumann reaction conditions (use of a two-phase solvent system) in the presence of a water solution of NaHCO3 for liberation of free amine, produced the desired lopinavir (34.1.21) in high yield and purity (Scheme 34.10.).

Scheme 34.10. The synthesis of lopinavir.

Lopinavir is a novel and strong protease inhibitor developed from ritonavir with high specificity for HIV-1 protease [139-141]. It is indicated, in combination with other antiretroviral agents, for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Numerous clinical trials have shown that lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) is highly effective as a component of highly active antiretroviral therapy [142,143].

Ritonavir is indicated in combination with other antiretroviral agents for the treatment of HIV-1-infected patients (adults and children of two years of age and older).[1][2]

PATENT

https://patents.google.com/patent/EP1133485B1/en

- [0002]

- [0003]

The synthesis process in question was subsequently optimised in its various parts by Abbot, who then described and claimed the individual improvements in the patent documents listed below: US 5,354,866, US 5,541,206, US 5,491,253, WO98/54122, WO 98/00393 and WO 99/11636.

- [0004]

The process for the synthesis of Ritonavir carried out on the basis of the above-mentioned patent documents requires, however, a particularly large number of intermediate stages; it is also unacceptable from the point of view of so-called “low environmental impact chemical synthesis” (B.M.Trost Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. (1995) 34, 259-281) owing to the increased use of activating groups and protective groups which necessitate not inconsiderable additional work in disposing of the by-products of the process, with a consequent increase in the overall manufacturing costs.

- [0005]

The object of the present invention is therefore to find a process for the synthesis of Ritonavir which requires a smaller number of intermediate stages and satisfies the requirements of low environmental impact chemical synthesis, thus limiting “waste of material”.

- [0006]

A process has now been found which, by using as starting materials the same compounds as those used in WO 94/14436, leads to the formation of Ritonavir in only five stages and with a minimum use of carbon atoms that are not incorporated in the final molecule.

EXAMPLESStage 1

- [0014]

- [0015]

Compound Val-NCA 2 was added to a solution of amine 1 (note 1, 2) in dichloromethane (60 ml) at -15°C under nitrogen followed by a solution of triethylamine in dichloromethane (48 ml) (note 3). The reaction mixture was maintained under agitation at from -15° to -13°C for two hours (note 4). The solution was used directly for the next stage without further purification.

- Note 1. Amine 1 was prepared using the procedure described in A.R. Haight et al. Org. Proc. Res. Develop. (1999) 3, 94-100.

- Note 2. Amine 1 was a mixture of stereoisomers with a ratio of 80 : 3.3 : 2.1 : 1.9.

- Note 3. This solution was added dropwise over a period of 25 minutes.

- Note 4. HPLC analysis after 2 hours: Amide 3 70.2 % – starting material 4.3 %

Stage 2

- [0016]

Reagent Molecular weight Amount Mmol Eq. Amine 3 Solution from stage 1 563.78 32.282 1 Triethylamine 101.19 (d = 0.726) 2.6 ml 18.654 0.6 Bis(trichloromethyl) carbonate (BTC) 296.75 3.5 g 11.794 0.36 dichloromethane 65 ml N-Methyl-4-aminomethyl-2-isopropylthiazole 4 170.27 5.5 g 32.282 1 triethylamine 101.19 6.9 ml 49.504 1.5 (d = 0.726) Dichloromethane 52 ml - [0017]

The triethylamine was added slowly to the solution of amine 3 resulting from stage 1 and this mixture was in turn added slowly to a solution of BTC in dichloromethane (65 ml) at from -15° to -13°C and the reaction mixture was maintained under agitation at that temperature for 1.5 hours (note 1). A solution of amine 4 and triethylamine in dichloromethane (52 ml) was then added slowly to the reaction mixture (note 2) and maintained under agitation at that temperature for one hour (note 3). The reaction was stopped with water (97 ml) and the two phases were separated. The organic phase was washed with a 10% aqueous citric acid solution, filtered over Celite and evaporated with a yield of 25 g of crude urea 5 which was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (eluant: toluene – ethyl acetate 6:4) to give 9.4 g of pure compound 5 (total yield of the two stages 38%) (note 4).

- Note 1. HPLC analysis after 1.5 hours of the reaction stopped in tert-butylamine: Amide 3 = 0.41 % – intermediate isocyanate = 61.3 %

- Note 2. The solution of amine 4 was added over a period of approximately 20 minutes.

- Note 3. HPLC analysis after 1 hour: Amide 3 = 7 % – Urea 5 = 54 %

- Note 4. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.31 (m, 4H), 7.28-7.24 (m, 4H), 7.21-7.14 (m, 8H), 7.11 (d, 2H), 7.05 (d, 2H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.75 (bd, 1H), 5.96 (bs, 1H), 4.48 (d, 1H), 4.39 ( d, 1H), 4.13 (dd, 1H), 4.09 (m, 1H), 3.93 (bd, 2H), 3.56 (bt, 1H), 3.39 (d, 2H), 3.28 (m, 1H), 3.04 (dd, 1H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 2.89 (m, 1H), 2.74 (q, 1H), 2.61 (m, 2H), 2.25 (m, 1H), 1.53 ( ddd, 1H), 1.38 (d, 6H), 1.28 (dt, 1H), 0.98 (d, 3H), 0.91 (d, 3H).

Stage 3

- [0018]

- [0019]

The Pearlman catalyst (note 1) was added to a solution of urea 5 in acetic acid and the mixture was hydrogenated for 5 hours at from 4 to 4.5 bar and from 78 to 82°C (note 2). The catalyst was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was dissolved in water (35 ml), the pH was adjusted to a value of 8 with NaOH, and extracted with CH2Cl2 (2×15 ml). The organic phase was washed with water (10 ml) and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure with a yield of 1.8 g of amine 6 as a free base which was used for the next stage without further purification (note 3, 4).

- Note 1. Of the various reaction conditions tested, such as HCOONH4/Pd-C in MeOH, H2/Pd-C in methanol, H2Pd-C/CH3SO3H in methanol, H2/Pd(OH)2/C in methanol, etc., the best conditions we have found hitherto are those described in this Example.

- Note 2. HPLC analysis after 5 hours: amine 6 = 52 % – monobenzyl derivative = 9.3%.

- Note 3. HPLC analysis on the free base: amine 6 = 54 % – monobenzyl derivative = 6%.

- Note 4. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.29 (m, 4H), 7.22-7.14 (m, 6H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.83 (bd, 1H), 6.15 (bs, 1H), 4.49 (d, 1H), 4.41 ( d, 1H), 4.25 (m, 1H), 4.08 (m, 1H), 3.38 (m, 1H), 3.29 (m, 1H), 2.99 (s, 3H), 2.92 (dd 1H), 2.84 (m, 2H), 2.76 (m, 1H), 2.47 (m, 1H), 2.28 (m, 1H), 1.76 ( dt, 1H), 1.61 (dt, 1H), 1.38 (d, 6H), 0.95 (d, 3H), 0.89 (d, 3H).

Stage 4

- [0020]

- [0021]

A solution of the chloride of compound 7 in ethyl acetate was treated with an aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution. The phases were separated and the organic phase was added to a solution of amine 6 in ethyl acetate. The reaction mixture was heated at 60°C for 12 hours, then concentrated; ammonia was added and the solution was maintained under agitation for 1 hour. The organic phase was washed with a 10% aqueous potassium carbonate solution (3x5ml) and with a saturated sodium chloride solution (5 ml); the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (eluant ethyl acetate) to give 900 mg of pure Ritonavir (total yield of the two stages 27 %) (note 1).

- Note 1. 1H-NMR (DMSO, 600 MHz) δ 9.05(s, 1H), 7.86 (s, 1H), 7.69 (d, 1H), 7.22-7.10 (m,11H), 6.88 (d, 1H), 6.02 (d, 1H), 5.16 (d, 1H), 5.12 (d, 1H), 4.60 (bs, 1H), 4.48 (d, 1H), 4.42 (d, 1H), 4.15 (m, 1H), 3.94 (dd, 1H), 3.83 (m, 1H), 3.59 (bt, 1H), 3.23 (m, 1H), 2.87 (s, 3H), 2.69-2.63 (m, 3H), 2.60 (m, 1H), 1.88 (m, 1H), 1.45 (m, 2H), 1.30 (d, 6H), 0.74 (d, 6H).

Side effects

When administered at the initially tested higher doses effective for anti-HIV therapy, the side effects of ritonavir are those shown below.[10]

- asthenia, malaise

- diarrhea

- nausea and vomiting

- abdominal pain

- dizziness

- insomnia

- sweating

- taste abnormality

- metabolic effects, including

- hypercholesterolemia

- hypertriglyceridemia

- elevated transaminases

- elevated creatine kinase

One of ritonavir’s side effects is hyperglycemia, through inhibition of the GLUT4 insulin-regulated transporter, thus keeping glucose from entering fat and muscle cells.[medical citation needed] This can lead to insulin resistance and cause problems for people with type 2 diabetes.[medical citation needed]

Drug interactions

Ritonavir induces CYP 1A2 and inhibits the major P450 isoforms 3A4 and 2D6.[according to whom?][medical citation needed] Concomitant therapy of ritonavir with a variety of medications may result in serious and sometimes fatal drug interactions.[11] The list of clinically significant interactions of ritonavir includes the following drugs:

Mechanism of action

Ritonavir was originally developed as an inhibitor of HIV protease, one of a family of pseudo-C2-symmetric small molecule inhibitors.

Ritonavir (center) bound to the active site of HIV protease.[medical citation needed]

Ritonavir is now rarely used for its own antiviral activity but remains widely used as a booster of other protease inhibitors. More specifically, ritonavir is used to inhibit a particular enzyme, in intestines, liver, and elsewhere, that normally metabolizes protease inhibitors, cytochrome P450-3A4 (CYP3A4).[16] The drug binds to and inhibits CYP3A4, so a low dose can be used to enhance other protease inhibitors. This discovery drastically reduced the adverse effects and improved the efficacy of protease inhibitors and HAART. However, because of the general role of CYP3A4 in xenobiotic metabolism, dosing with ritonavir also affects the efficacy of numerous other medications, adding to the challenge of prescribing drugs concurrently.[medical citation needed][17][better source needed]

Pharmocodymanics and pharmacokinetics

The capsules of the medication do not have the same bioavailability as the tablets.[2]

History

New HIV infections and deaths, before and after the FDA approval of “highly active antiretroviral therapy”,[18] of which saquinavir and ritonavir were key as the first two protease inhibitors.[medical citation needed] As a result of the new therapies, HIV deaths in the United States fell dramatically within two years.[18]

Ritonavir is manufactured as Norvir by AbbVie, Inc..[citation needed] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ritonavir on March 1, 1996,[19] making it the seventh U.S.-approved antiretroviral drug and the second U.S.-approved protease inhibitor (after saquinavir four months earlier).[citation needed] As a result of the introduction of new “highly active antiretroviral thearap[ies]”—of which the protease inhibitors ritonavir and saquinavir were critical[citation needed]—the annual U.S. HIV-associated death rate fell from over 50,000 to about 18,000 over a period of two years.[20][21]

In 2003, Abbott (now AbbVie, Inc.) raised the price of a Norvir course from US$1.71 per day to US$8.57 per day, leading to claims of price gouging by patients’ groups and some members of Congress. Consumer group Essential Inventions petitioned the NIH to override the Norvir patent, but the NIH announced on August 4, 2004, that it lacked the legal right to allow generic production of Norvir.[22]

In 2014, the FDA approved a combination of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 4,[3] where the presence of ritonavir again capitalizes on its inhibitory interaction with the human drug metabolic enzyme CYP3A4.

Polymorphism and temporary market withdrawal

Ritonavir was originally dispensed as an ordinary capsule that did not require refrigeration. This contained a crystal form of ritonavir that is now called form I.[23] However, like many drugs, crystalline ritonavir can exhibit polymorphism, i.e., the same molecule can crystallize into more than one crystal type, or polymorph, each of which contains the same repeating molecule but in different crystal packings/arrangements. The solubility and hence the bioavailability can vary in the different arrangements, and this was observed for forms I and II of ritonavir.[24]

During development—ritonavir was introduced in 1996—only the crystal form now called form I was found; however, in 1998, a lower free energy,[25] more stable polymorph, form II, was discovered. This more stable crystal form was less soluble, which resulted in significantly lower bioavailability. The compromised oral bioavailability of the drug led to temporary removal of the oral capsule formulation from the market.[24] As a consequence of the fact that even a trace amount of form II can result in the conversion of the more bioavailable form I into form II, the presence of form II threatened the ruin of existing supplies of the oral capsule formulation of ritonavir; and indeed, form II was found in production lines, effectively halting ritonavir production.[23] Abbott (now AbbVie) withdrew the capsules from the market, and prescribing physicians were encouraged to switch to a Norvir suspension.[citation needed]

The company’s research and development teams ultimately solved the problem by replacing the capsule formulation with a refrigerated gelcap.[when?][citation needed] In 2000, Abbott (now AbbVie) received FDA-approval for a tablet formulation of lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) which contained a preparation of ritonavir that did not require refrigeration.[26]

Research

In 2020, the fixed-dose combination of lopinavir/ritonavir was found not to work in severe COVID-19.[27] In the trial the medication was started around thirteen days after the start of symptoms.[27] Virtual screening of the 1930 FDA-approved drugs followed by molecular dynamics analysis predicted ritonavir blocks the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (hACE2) receptor, which is critical for the virus entry into human cells.[28]

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Norvir EPAR”. European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 20 August 2020. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k “Ritonavir”. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-10-17. Retrieved Oct 23, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “FDA approves Viekira Pak to treat hepatitis C”. Food and Drug Administration. December 19, 2014. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015.

- ^ “Ritonavir Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings”. drugs.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b British National Formulary 69 (69 ed.). Pharmaceutical Pr. March 31, 2015. p. 426. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ Hacker, Miles (2009). Pharmacology principles and practice. Amsterdam: Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 550. ISBN 9780080919225.

- ^ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 509. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ “First Generic Drug Approvals”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ “Norvir side effects (Ritonavir) and drug interactions – prescription drugs and medications at RxList”. June 27, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-06-27.

- ^ “Ritonavir: Drug Information Provided by Lexi-Comp: Merck Manual Professional”. April 30, 2008. Archived from the originalon 2008-04-30.

- ^ Henry, J. A.; Hill, I. R. (1998). “Fatal interaction between ritonavir and MDMA”. Lancet. 352 (9142): 1751–1752. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79824-x. PMID 9848354. S2CID 45334940.

- ^ Papaseit, E.; Vázquez, A.; Pérez-Mañá, C.; Pujadas, M.; De La Torre, R.; Farré, M.; Nolla, J. (2012). “Surviving life-threatening MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, ecstasy) toxicity caused by ritonavir (RTV)”. Intensive Care Medicine. 38 (7): 1239–1240. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2537-9. PMID 22460853. S2CID 19375709.

- ^ Nieminen, Tuija H.; Hagelberg, Nora M.; Saari, Teijo I.; Neuvonen, Mikko; Neuvonen, Pertti J.; Laine, Kari; Olkkola, Klaus T. (2010). “Oxycodone concentrations are greatly increased by the concomitant use of ritonavir or lopinavir/ritonavir”. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 66 (10): 977–985. doi:10.1007/s00228-010-0879-1. ISSN 0031-6970. PMID 20697700. S2CID 25770818.

- ^ Hsieh, Yi-Ling; Ilevbare, Grace A.; Van Eerdenbrugh, Bernard; Box, Karl J.; Sanchez-Felix, Manuel Vincente; Taylor, Lynne S. (2012-05-12). “pH-Induced Precipitation Behavior of Weakly Basic Compounds: Determination of Extent and Duration of Supersaturation Using Potentiometric Titration and Correlation to Solid State Properties”. Pharmaceutical Research. 29 (10): 2738–2753. doi:10.1007/s11095-012-0759-8. ISSN 0724-8741. PMID 22580905. S2CID 15502736.

- ^ Zeldin RK, Petruschke RA (2004). “Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected patients”. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 53 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh029. PMID 14657084.

- ^ “Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration(FDA). December 3, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b (PDF)https://web.archive.org/web/20150924044850/http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm6021.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF)on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2020-02-17. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ “Ritonavir FDA approval package” (PDF). 1 March 1996.

- ^ “HIV Surveillance—United States, 1981-2008”. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ The CDC, in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, ascribes this to “highly active antiretroviral therapy”, without mention of either of these drugs, see the preceding citation. A further citation is needed to make this accurate connection between this drop and the introduction of the protease inhibitors.

- ^ Ceci Connolly (2004-08-05). “NIH Declines to Enter AIDS Drug Price Battle”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2006-01-16.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bauer J; et al. (2001). “Ritonavir: An Extraordinary Example of Conformational Polymorphism”. Pharmaceutical Research. 18 (6): 859–866. doi:10.1023/A:1011052932607. PMID 11474792. S2CID 20923508.

- ^ Jump up to:a b S. L. Morissette; S. Soukasene; D. Levinson; M. J. Cima; O. Almarsson (2003). “Elucidation of crystal form diversity of the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir by high-throughput crystallization”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100 (5): 2180–84. doi:10.1073/pnas.0437744100. PMC 151315. PMID 12604798.

- ^ Lüttge, Andreas (February 1, 2006). “Crystal dissolution kinetics and Gibbs free energy”. Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena. 150 (2): 248–259. doi:10.1016/j.elspec.2005.06.007.

- ^ “Kaletra FAQ”. AbbVie’s Kaletra product information. AbbVie. 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cao, Bin; Wang, Yeming; Wen, Danning; Liu, Wen; Wang, Jingli; Fan, Guohui; et al. (18 March 2020). “A Trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19”. New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (19): 1787–1799. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. PMC 7121492. PMID 32187464.

- ^ Bagheri, Milad; Niavarani, Ahmadreza (2020-10-08). “Molecular dynamics analysis predicts ritonavir and naloxegol strongly block the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-hACE2 binding”. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics: 1–10. doi:10.1080/07391102.2020.1830854. ISSN 0739-1102. PMID 33030105. S2CID 222217607.

Further reading

- Chemburkar, Sanjay R.; Bauer, John; Deming, Kris; Spiwek, Harry; Patel, Ketan; Morris, John; Henry, Rodger; Spanton, Stephen; et al. (2000). “Dealing with the Impact of Ritonavir Polymorphs on the Late Stages of Bulk Drug Process Development”. Organic Process Research & Development. 4 (5): 413–417. doi:10.1021/op000023y.

External links

- “Ritonavir”. Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Norvir |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a696029 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 98-99% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 3-5 hours |

| Excretion | mostly fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.710 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C37H48N6O5S2 |

| Molar mass | 720.95 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

|

/////////////RITONAVIR, Antiviral, Peptidomimetics, HIV Protease Inhibitor, A-84538, Abbott 84538, ABBOTT-84538, ABT 538, ABT-538, DRG-0244, NSC-693184, TMC 114r

CC(C)[C@H](NC(=O)N(C)CC1=CSC(=N1)C(C)C)C(=O)N[C@H](C[C@H](O)[C@H](CC1=CC=CC=C1)NC(=O)OCC1=CN=CS1)CC1=CC=CC=C1