RN: 1360457-46-0

UNII: 1C75676F8V

- Originator Rempex Pharmaceuticals

- Developer The Medicines Company; US Department of Health and Human Services

- Class Antibacterials; Pyrrolidines; Small molecules; Thienamycins

- Mechanism of Action Beta lactamase inhibitors; Cell wall inhibitors

Highest Development Phases

- Registered Urinary tract infections

- Phase III Bacteraemia; Gram-negative infections; Pneumonia; Pyelonephritis

Most Recent Events

- 29 Aug 2017 Registered for Urinary tract infections (Treatment-experienced, Treatment-resistant) in USA (IV) – First global approval

- 29 Aug 2017 Updated efficacy and safety data from a phase III trial in Gram-negative infections released by The Medicines Company

- 09 Aug 2017 Planned Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) date for Urinary tract infections (Treatment-experienced, Treatment-resistant) in USA (IV) is 2017-08-29

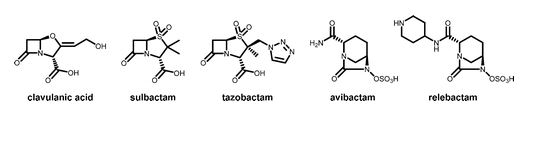

Next generation β-lactamase inhibitors recently approved or in clinical trials. A. Avibactam. B. Relebactam. C. Vaborbactam.

Next generation β-lactamase inhibitors recently approved or in clinical trials. A. Avibactam. B. Relebactam. C. Vaborbactam.

Vaborbactam (INN)[1] is a non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor discovered by Rempex Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of The Medicines Company. While not effective as an antibiotic by itself, it restores potency to existing antibiotics by inhibiting the beta-lactamase enzymes that would otherwise degrade them. When combined with an appropriate antibiotic it can be used for the treatment of gram-negative bacterial infections.[2]

According to a Medicines Company press release, as of June 2016 a combination of vaborbactam with the carbapenem antibiotic meropenem had met all pre-specified primary endpoints in a phase III clinical trial in patients with complicated urinary tract infections.[3] The company planned to submit an NDA to the FDAin early 2017.

Biochemistry

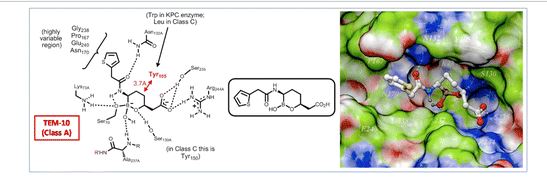

Carbapenemases are a family of β-lactamase enzymes distinguished by their broad spectrum of activity and their ability to degrade carbapenem antibiotics, which are frequently used in the treatment of multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections.[4] Carbapenemases can be broadly divided into two different categories based on the mechanism they use to hydrolyze the lactam ring in their substrates. Metallo-β-lactamases contain bound zinc ions in their active sites and are therefore inhibited by chelating agents like EDTA, while serine carbapenemases feature an active site serine that participates in the hydrolysis of the substrate.[4] Serine carbapenemase-catalyzed hydrolysis employs a three-step mechanism featuring acylation and deacylation steps analogous to the mechanism of protease-catalyzed peptide hydrolysis, proceeding through a tetrahedral transition state.[4][5]

Boronic acids are unusual in their ability to reversibly form covalent bonds with alcohols such as the active site serine in a serine carbapenemase. This property enables them to function as transition state analogs of serine carbapenemase-catalyzed lactam hydrolysis and thereby inhibit these enzymes. Based on data from Hecker et al., vaborbactam is a potent inhibitor of a variety of β-lactamases, exhibiting a 69-nanomolar {\displaystyle K_{i}}

Given their mechanism of action, the possibility of off-target effects brought about through inhibition of endogenous serine hydrolases is an obvious possible concern in the development of boronic acid β-lactamase inhibitors, and in fact boronic acids like bortezomib have previously been investigated or developed as inhibitors of various human proteases.[2] Vaborbactam, however, is a highly specific β-lactamase inhibitor, with an IC50 >> 1 mM against all human serine hydrolases against which it has been tested.[2] Consistent with its high in vitro specificity, vaborbactam exhibited a good safety profile in human phase I clinical trials, with similar adverse events observed in both placebo and treatment groups.[6] Hecker et al. argue this specificity results from the higher affinity of human proteases to linear molecules; thus it is expected that a boron heterocycle will have zero effect on them.

SYN

WO 2015171430

PATENT

| Inventors | Gavin Hirst, Raja Reddy, Scott Hecker, Maxim Totrov, David C. Griffith, Olga Rodny, Michael N. Dudley, Serge Boyer, Less « |

| Applicant | Rempex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. |

Antibiotics have been effective tools in the treatment of infectious diseases during the last half-century. From the development of antibiotic therapy to the late 1980s there was almost complete control over bacterial infections in developed countries. However, in response to the pressure of antibiotic usage, multiple resistance mechanisms have become widespread and are threatening the clinical utility of antibacterial therapy. The increase in antibiotic resistant strains has been particularly common in major hospitals and care centers. The consequences of the increase in resistant strains include higher morbidity and mortality, longer patient hospitalization, and an increase in treatment costs

[0003] Various bacteria have evolved β-lactam deactivating enzymes, namely, β-lactamases, that counter the efficacy of the various β-lactams. β-lactamases can be grouped into 4 classes based on their amino acid sequences, namely, Ambler classes A, B, C, and D. Enzymes in classes A, C, and D include active-site serine β-lactamases, and class B enzymes, which are encountered less frequently, are Zn-dependent. These enzymes catalyze the chemical degradation of β-lactam antibiotics, rendering them inactive. Some β-lactamases can be transferred within and between various bacterial strains and species. The rapid spread of bacterial resistance and the evolution of multi- resistant strains severely limits β-lactam treatment options available.

[0004] The increase of class D β-lactamase-expressing bacterium strains such as Acinetobacter baumannii has become an emerging multidrug-resistant threat. A. baumannii strains express A, C, and D class β-lactamases. The class D β-lactamases such as the OXA families are particularly effective at destroying carbapenem type β-lactam antibiotics, e.g., imipenem, the active carbapenems component of Merck’s Primaxin® (Montefour, K.; et al. Crit. Care Nurse 2008, 28, 15; Perez, F. et al. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2008, 6, 269; Bou, G.; Martinez-Beltran, J. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 40, 428. 2006, 50, 2280; Bou, G. et al, J. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1556). This has imposed a pressing threat to the effective use of drugs in that category to treat and prevent bacterial infections. Indeed the number of catalogued serine-based β- lactamases has exploded from less than ten in the 1970s to over 300 variants. These issues fostered the development of five “generations” of cephalosporins. When initially released into clinical practice, extended- spectrum cephalosporins resisted hydrolysis by the prevalent class A β-lactamases, TEM-1 and SHV-1. However, the development of resistant strains by the evolution of single amino acid substitutions in TEM-1 and SHV-1 resulted in the emergence of the extended- spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) phenotype.

[0005] New β-lactamases have recently evolved that hydrolyze the carbapenem class of antimicrobials, including imipenem, biapenem, doripenem, meropenem, and ertapenem, as well as other β-lactam antibiotics. These carbapenemases belong to molecular classes A, B, and D. Class A carbapenemases of the KPC-type predominantly in Klebsiella pneumoniae but now also reported in other Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. The KPC carbapenemase was first described in 1996 in North Carolina, but since then has disseminated widely in the US. It has been particularly problematic in the New York City area, where several reports of spread within major hospitals and patient morbidity have been reported. These enzymes have also been recently reported in France, Greece, Sweden, United Kingdom, and an outbreak in Germany has recently been reported. Treatment of resistant strains with carbapenems can be associated with poor outcomes.

[0006] Another mechanism of β-lactamase mediated resistance to carbapenems involves combination of permeability or efflux mechanisms combined with hyper production of beta-lactamases. One example is the loss of a porin combined in hyperproduction of ampC beta-lactamase results in resistance to imipenem in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Efflux pump over expression combined with hyperproduction of the ampC β-lactamase can also result in resistance to a carbapenem such as meropenem.

[0007] Because there are three major molecular classes of serine-based β- lactamases, and each of these classes contains significant numbers of β-lactamase variants, inhibition of one or a small number of β-lactamases is unlikely to be of therapeutic value. Legacy β-lactamase inhibitors are largely ineffective against at least Class A carbapenemases, against the chromosomal and plasmid-mediated Class C cephalosporinases and against many of the Class D oxacillinases. Therefore, there is a need for improved β-lactamase inhibitors.

The following compounds are prepared starting from enantiomerically pure (R)-tert-butyl 3-hydroxypent-4-enoate (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4175-4177) in accordance with the procedure described in the above Example 1.

5

[0192] 2-((3R,6S)-2-hydroxy-3-(2-(thiophen-2-yl)acetamido)-l,2-oxaborinan-6-yl)acetic acid 5. 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ ppm 0.97-1.11 (q, IH), 1.47-1.69 (m, 2H), 1.69-1.80 (m, IH), 2.21-2.33 (td, IH), 2.33-2.41 (dd, IH), 2.58-2.67 (m, IH), 3.97 (s, 2H), 4.06-4.14 (m, IH), 6.97-7.04 (m, IH), 7.04-7.08 (m, IH), 7.34-7.38 (dd, IH); ESIMS found for Ci2Hi6BN05S m/z 28 -H20)+.

The following compounds are prepared starting from enantiomerically pure (R)-tert-butyl 3-hydroxypent-4-enoate (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4175-4177) in accordance with the procedure described in the above Example 1.

5

[0175] 2-((3R,6S)-2-hydroxy-3-(2-(thiophen-2-yl)acetamido)-l,2-oxaborinan-6- yl)acetic acid 5. 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ ppm 0.97-1.11 (q, 1H), 1.47-1.69 (m, 2H), 1.69-1.80 (m, 1H), 2.21-2.33 (td, 1H), 2.33-2.41 (dd, 1H), 2.58-2.67 (m, 1H), 3.97 (s, 2H), 4.06-4.14 (m, 1H), 6.97-7.04 (m, 1H), 7.04-7.08 (m, 1H), 7.34-7.38 (dd, 1H); ESIMS found for Ci2Hi6BN05S m/z 280 (100%) (M-H20)+.

EXAMPLES

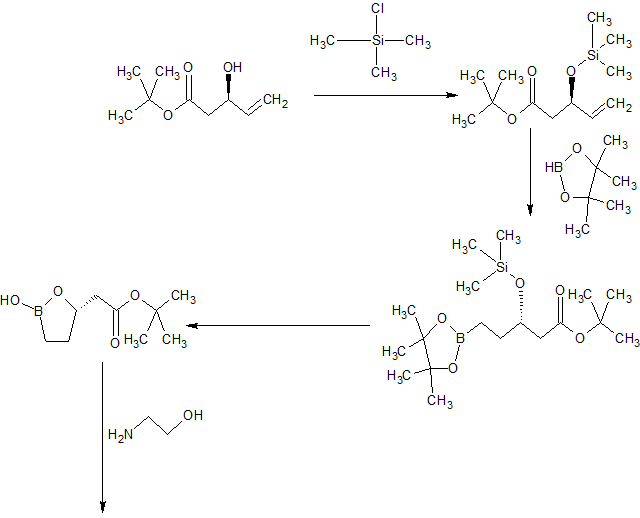

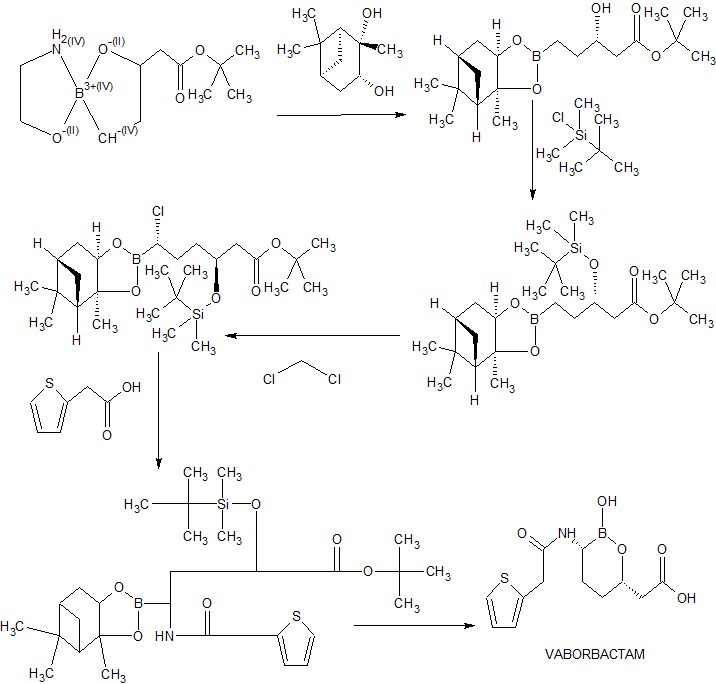

Example 1 – Synthesis of Intermediate Compound 10

[0191] The compound of Formula 10 was synthesized as shown in Scheme 3, below:

Scheme 3

95%

80% for 2 steps

(i?)-t-butyl 3-(trimethysilyloxy)-pent-4-enoate (7)

[0192] Chlorotrimethylsilane (4.6 mL, 36.3 mmol, 1.25 eq) was added to a solution of (R)-t-butyl 3-hydroxy-pent-4-enoate (1, 5 g, 29 mmol) and triethylamine (5.3 mL, 37.3 mmol, 1.3 eq) in dichloromethane (25 mL) keeping the temperature below 30 °C. After completion of the addition, the white heterogeneous mixture was stirred at rt for 20 minutes (TLC, GC, note 2) then quenched with MeOH (352 μί, 0.3 eq). After stirring at rt for 5 minutes, the white heterogeneous reaction mixture was diluted with heptane (25 mL). The salts were filtered off and rinsed with heptane (2 x 10 mL). The combined turbid filtrates were washed with a saturated solution of NaHC03 (2 x 25 mL) and concentrated to dryness. The residual oil was azeotroped with heptane (25 mL) to give a colorless oil that was used immediately.

QSVt-butyl 3-(trimethylsilyloxy)-5-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-[L3,21dioxaborolan-2-yl)-pentanoate (8)

[0193] A solution of bis-diphenylphosphino-ethane (46.3 mg, 0.2 mol%) and [Ir(COD)Cl]2 (39 mg, 0.1 mol%) in CH2C12 (5 mL) was added to a refluxing solution of crude TMS-protected pentenoate 7. Pinacol borane (9.3 mL,l .l eq) was added to the

refluxing solution. After stirring at reflux for 3 h, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, concentrated to dryness and taken up in heptane (50 mL). The insolubles were filtered over Celite and rinse with heptane (10 mL).

Ethanolamine-boronic acid salt (10)

[0194] A mixture of fully protected boronate 8 (5.0 g, 13.4 mmol), 0.5 N HC1 (5 mL) and acetone (0.5 mL) was stirred vigorously at room temperature, providing intermediate 9. After complete consumption of the starting material, a solution of NaI04 (3.44 g, 1.2 eq) in water (15 mL) was added slowly keeping the temperature <30 °C. Upon the completion of the addition (30 min), the reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature. After consumption of all pinacol, MTBE (5 mL) was added. After stirring at room temperature for 10 min, the white solids were filtered off and rinsed with MTBE (2 x 5 mL). The filtrate was partitioned and the aqueous layer was extracted with MTBE (10 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed sequentially with a 0.1 M NaHS03 solution (2 x 5 mL), a saturated NaHC03 solution (5 mL) and brine (5 mL). The organic layer was concentrated to dryness. The residue was taken up in MTBE (15 mL) and the residual salts filtered off. The filtrate was concentrated to dryness and the residue was taken up in MTBE (10 mL) and acetonitrile (1.7 mL). Ethanolamine (0.99 mL, 1.1 eq) was added. After stirring at room temperature for 1 hour, the heterogeneous mixture was stirred at 0 °C. After stirring at 0 °C for 2 hours, the solids were collected by filtration, rinsed with MTBE (2 x 5 mL), air dried then dried under high vacuum to give Compound 10 as a white granular powder.

Example 2 – Preparation of Beta-Lactamase Inhibitor (15)

[0195] The compound of Formula 15 was synthesized as shown in Scheme 4 below:

Scheme 4

Synthesis of pinanediol boronate (12)

[0196] Ethanolammonium boronate 11 (15 g, 61.7 mmol) and pinanediol (10.5 g, 61.7 mmol, 1 eq) were suspended in MTBE (75 mL). Water (75 mL) was added and the yellow biphasic heterogeneous mixture was stirred at room temperature. After stirring for 2 hours at room temperature, some pinanediol was still present and stirring was continued overnight. The layers were separated and the organic layer was washed with brine, concentrated under reduced pressure and azeotroped with MTBE (2 x 30 mL). The residual oil was taken up in dichloromethane (40 mL). In another flask, TBSC1 (1 1.6 g, 77.1 mmol, 1.25 eq) was added to a solution of imidazole (9.66 g, 141.9 mmol, 2.3 eq) in dichloromethane (25 mL). The white slurry was stirred at room temperature. After 5 minutes, the solution of pinanediol boronate was added to the white slurry and the flask was rinsed with dichloromethane (2 x 5 mL). The heterogeneous reaction mixture was heated at reflux temeprature. After stirring at reflux for 8 hours, the reaction mixture was cooled to 30 °C and TMSC1 (330 \JL) was added. After stirring 30 minutes at 30 °C, MeOH (15 mL) was added. After stirring at room temperature overnight, the reaction mixture was washed sequentially with 0.5 N HC1 (115 niL), 0.5 N HC1 (60 n L) and saturated NaHC03 (90 niL). The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure and azeotroped with heptane (150 n L) to give 12 as a yellow oil (27.09 g, 94.1%) which was used without purification.

Synthesis of chloroboronate (13)

[0197] A solution of n-butyllithium (2.5 M in hexane, 29.6 niL, 74.1 mmol, 1.3 eq) was added to THF (100 mL) at -80 °C. The resulting solution was cooled to -100 °C. A solution of dichloromethane (14.6 mL, 228 mmol, 4 eq) in THF (25 mL) was added via syringe pump on the sides of the flask keeping the temperature < -95 °C. During the second half of the addition a precipitate starts to appear which became thicker with the addition of the remaining dichloromethane solution. After stirring between -100 and -95 °C for 30 min, a solution of 12 (26.59 g, 57 mmol) in THF (25 mL) was added by syringe pump on the sides of the flask while maintaining the batch temperature < -95 °C to give a clear yellow solution. After stirring between -100 and -95 °C for 30 min, a solution of zinc chloride (1 M in ether, 120 mL, 120 mmol, 2.1 eq) was added keeping the temperature < -70 °C. The reaction mixture was then warmed to room temperature (at about -18 °C the reaction mixture became turbid/heterogeneous). After stirring at room temperature for 2 hours, the reaction mixture was cooled to 15 °C and quenched with 1 N HC1 (100 mL). The layers were separated and the organic layer was washed sequentially with 1 N HC1 (100 mL) and water (2 x 100 mL), concentrated to oil and azeotroped with heptane (3 x 150 mL) to provide 13 as a yellow oil (30.03 g, 102%) which was used without purification.

Synthesis of (14)

[0198] LiHMDS (1 M in THF, 63 mL, 62.7 mmol, 1.1 eq) was added to a solution of 13 (29.5 g, 57 mmol) in THF (60 mL) while maintaining the batch temperature at < -65 °C. After stirring at -78 °C for 2 hours, additional LiHMDS (5.7 mL, 0.1 eq) was added to consume the remaining starting material. After stirring at -78 °C for 30 minutes, the tan reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature. After stirring at room temperature for one hour, the solution of silylated amine was added via cannula to a solution of HOBT ester of 2-thienylacetic acid in acetonitrile at 0 °C (the solution of HOBT ester was prepared by adding EDCI (16.39 g, 85.5 mmol, 1.5 eq) to a suspension of recrystallized 2-thienylacetic acid (9.73 g, 68.4 mmol, 1.2 eq) and HOBT.H20 (11.35 g, 74.1 mmol, 1.3 eq) in acetonitrile (10 mL) at 0 °C. The clear solution was stirred at 0 °C for 30 minutes prior to the addition of the silylated amine). After stirring at 0 °C for one hour, the heterogeneous reaction mixture was placed in the fridge overnight. Saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate (80 mL) and heptane (80 mL) were added, and after stirring 30 minutes at room temperature, the layers were separated. The organic layer was washed with saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate (2 x 80 mL) and filtered through Celite. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and the tan oil was azeotroped with heptane (3 x 1 10 mL). The residue was taken up in heptane (60 mL) and seeds were added. After stirring at room temperature for one hour, the reaction mixture became heterogeneous. After stirring 4 hours at 0 °C, the solids were collected by filtration and washed with ice cold heptane (3 x 20 mL), air dried then dried under high vacuum to give 14 as an off white powder (10.95 g, 31%).

Synthesis of (15)

[0199] A mixture of 14 (10 g, 16.1 mmol), boric acid (1.3 g, 20.9 mmol, 1.3 eq), dioxane (20 mL), and 1 M sulfuric acid (10 mL) was heated at 75 °C. After stirring 7 hours at 75 °C, the cooled reaction mixture was diluted with water (10 mL) and MTBE (30 mL) and the residual mixture was cooled to 0 °C. The pH was adjusted to 5.0 with a solution of 2 N NaOH (14 mL). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with MTBE (2 x 30 mL) then concentrated to dryness. The residue was taken up in water (10 mL) and the solution was filtered through a 0.45 μηι GMF syringe filter. The flask and filter were rinsed with water (7.5 mL). The pH of the filtrate was lowered to 4.0 with 2 M H2SO4 and seeds (5 mg) were added. After stirring at room temperature for 10 minutes, the pH was lowered to 1.9 over 1 hour with 2 M H2S04 (total volume 3.5 mL). After stirring at room temperature for 2 hours, the solids were collected by filtration. The filtrate was recirculated twice to rinse the flask and the cake was washed with water (2 x 12 mL), air dried then dried under high vacuum to give 15 as a white powder (3.63 g, 76%).

|

Patent ID

|

Patent Title

|

Submitted Date

|

Granted Date

|

|

CYCLIC BORONIC ACID ESTER DERIVATIVES AND THERAPEUTIC USES THEREOF

|

2013-07-29

|

2013-12-26

|

|

|

Cyclic boronic acid ester derivatives and therapeutic uses thereof

|

2011-08-08

|

2014-03-25

|

|

|

CYCLIC BORONIC ACID ESTER DERIVATIVES AND THERAPEUTIC USES THEREOF

|

2013-03-15

|

2013-12-12

|

|

|

METHODS OF TREATING BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

|

2013-02-11

|

2015-04-30

|

References

- Jump up^ “International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN). Recommended International Nonproprietary Names: List 75” (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 161–2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Hecker, SJ; Reddy, KR; Totrov, M; Hirst, GC; Lomovskaya, O; Griffith, DC; King, P; Tsivkovski, R; Sun, D; Sabet, M; Tarazi, Z; Clifton, MC; Atkins, K; Raymond, A; Potts, KT; Abendroth, J; Boyer, SH; Loutit, JS; Morgan, EE; Durso, S; Dudley, MN (14 May 2015). “Discovery of a Cyclic Boronic Acid β-Lactamase Inhibitor (RPX7009) with Utility vs Class A Serine Carbapenemases”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 58 (9): 3682–92. ISSN 0022-2623. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00127.

- Jump up^ “The Medicines Company Announces Positive Top-Line Results for Phase 3 TANGO 1 Clinical Trial of CARBAVANCE®“. Business Wire, Inc.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Queenan, AM; Bush, K (13 July 2007). “Carbapenemases: the Versatile β-Lactamases”. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (3): 440–58. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 1932750

. PMID 17630334. doi:10.1128/CMR.00001-07.

. PMID 17630334. doi:10.1128/CMR.00001-07. - Jump up^ Lamotte-Brasseur, J; Knox, J; Kelly, JA; Charlier, P; Fonzé, E; Dideberg, O; Frère, JM (December 1994). “The Structures and Catalytic Mechanisms of Active-Site Serine β-Lactamases”. Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews. 12 (1): 189–230. ISSN 0264-8725. PMID 7727028. doi:10.1080/02648725.1994.10647912.

- Jump up^ Griffith, DC; Loutit, JS; Morgan, EE; Durso, S; Dudley, MN (October 2016). “Phase 1 Study of the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of the β-Lactamase Inhibitor Vaborbactam (RPX7009) in Healthy Adult Subjects”. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 60 (10): 6326–32. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 5038296

. PMID 27527080. doi:10.1128/AAC.00568-16.

. PMID 27527080. doi:10.1128/AAC.00568-16.

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration |

IV |

| ATC code |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H16BNO5S |

| Molar mass | 297.13 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

FDA approves new antibacterial drug Vabomere (meropenem, vaborbactam)

Meropenem

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved Vabomere for adults with complicated urinary tract infections (cUTI), including a type of kidney infection, pyelonephritis, caused by specific bacteria. Vabomere is a drug containing meropenem, an antibacterial, and vaborbactam, which inhibits certain types of resistance mechanisms used by bacteria.

“The FDA is committed to making new safe and effective antibacterial drugs available,” said Edward Cox, M.D., director of the Office of Antimicrobial Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “This approval provides an additional treatment option for patients with cUTI, a type of serious bacterial infection.”

The safety and efficacy of Vabomere were evaluated in a clinical trial with 545 adults with cUTI, including those with pyelonephritis. At the end of intravenous treatment with Vabomere, approximately 98 percent of patients treated with Vabomere compared with approximately 94 percent of patients treated with piperacillin/tazobactam, another antibacterial drug, had cure/improvement in symptoms and a negative urine culture test. Approximately seven days after completing treatment, approximately 77 percent of patients treated with Vabomere compared with approximately 73 percent of patients treated with piperacillin/tazobactam had resolved symptoms and a negative urine culture.

The most common adverse reactions in patients taking Vabomere were headache, infusion site reactions and diarrhea. Vabomere is associated with serious risks including allergic reactions and seizures. Vabomere should not be used in patients with a history of anaphylaxis, a type of severe allergic reaction to products in the class of drugs called beta-lactams.

To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of antibacterial drugs, Vabomere should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria.

Vabomere was designated as a qualified infectious disease product (QIDP). This designation is given to antibacterial products that treat serious or life-threatening infections under the Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) title of the FDA Safety and Innovation Act. As part of its QIDP designation, Vabomere received a priority review.

The FDA granted approval of Vabomere to Rempex Pharmaceuticals.

Moxalactam synthesis

Moxalactam synthesis

Latamoxef (or moxalactam)

http://www.wikiwand.com/en/Latamoxef

////////////////RPX7009, RPX 7009, VABORBACTAM, Vaborbactam, Ваборбактам , فابورباكتام , 法硼巴坦 , FDA 2017