AZITHROMYCIN

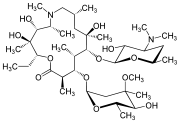

C38H72N2O12,

748.9845

アジスロマイシン;

| CAS: | 83905-01-5 |

| PubChem: | 51091811 |

| ChEBI: | 2955 |

| ChEMBL: | CHEMBL529 |

| DrugBank: | DB00207 |

| PDB-CCD: | ZIT[PDBj] |

| LigandBox: | D07486 |

| NIKKAJI: | J134.080H |

Azithromycin is an antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections.[3] This includes middle ear infections, strep throat, pneumonia, traveler’s diarrhea, and certain other intestinal infections.[3] It can also be used for a number of sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia and gonorrhea infections.[3] Along with other medications, it may also be used for malaria.[3] It can be taken by mouth or intravenously with doses once per day.[3]

Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and upset stomach.[3] An allergic reaction, such as anaphylaxis, QT prolongation, or a type of diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile is possible.[3] No harm has been found with its use during pregnancy.[3] Its safety during breastfeeding is not confirmed, but it is likely safe.[4] Azithromycin is an azalide, a type of macrolide antibiotic.[3] It works by decreasing the production of protein, thereby stopping bacterial growth.[3]

Azithromycin was discovered 1980 by Pliva, and approved for medical use in 1988.[5][6] It is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[7] The World Health Organization classifies it as critically important for human medicine.[8] It is available as a generic medication[9] and is sold under many trade names worldwide.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.18 to US$2.98 per dose.[10] In the United States, it is about US$4 for a course of treatment as of 2018.[11] In 2016, it was the 49th most prescribed medication in the United States with more than 15 million prescriptions.[12]

Medical uses

Azithromycin is used to treat many different infections, including:

- Prevention and treatment of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, or S. pneumoniae. The benefits of long-term prophylaxis must be weighed on a patient-by-patient basis against the risk of cardiovascular and other adverse effects.[13]

- Community-acquired pneumonia due to C. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. pneumoniae, or S. pneumoniae[14]

- Uncomplicated skin infections due to S. aureus, S. pyogenes, or S. agalactiae

- Urethritis and cervicitis due to C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae. In combination with ceftriaxone, azithromycin is part of the United States Centers for Disease Control-recommended regimen for the treatment of gonorrhea. Azithromycin is active as monotherapy in most cases, but the combination with ceftriaxone is recommended based on the relatively low barrier to resistance development in gonococci and due to frequent co-infection with C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae.[15]

- Trachoma due to C. trachomatis[16]

- Genital ulcer disease (chancroid) in men due to H. ducrey

- Acute bacterial sinusitis due to H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, or S. pneumoniae. Other agents, such as amoxicillin/clavulanate are generally preferred, however.[17][18]

- Acute otitis media caused by H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis or S. pneumoniae. Azithromycin is not, however, a first-line agent for this condition. Amoxicillin or another beta lactam antibiotic is generally preferred.[19]

- Pharyngitis or tonsillitis caused by S. pyogenes as an alternative to first-line therapy in individuals who cannot use first-line therapy[20]

Bacterial susceptibility

Azithromycin has relatively broad but shallow antibacterial activity. It inhibits some Gram-positive bacteria, some Gram-negative bacteria, and many atypical bacteria.

A strain of gonorrhea reported to be highly resistant to azithromycin was found in the population in 2015. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is normally susceptible to azithromycin,[21] but the drug is not widely used as monotherapy due to a low barrier to resistance development.[15] Extensive use of azithromycin has resulted in growing Streptococcus pneumoniae resistance.[22]

Aerobic and facultative Gram-positive microorganisms

- Staphylococcus aureus (Methicillin-sensitive only)

- Streptococcus agalactiae

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Streptococcus pyogenes

Aerobic and facultative Gram-negative microorganisms

- Haemophilus ducreyi

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Moraxella catarrhalis

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Bordetella pertussis

- Legionella pneumophila

Anaerobic microorganisms

- Peptostreptococcus species

- Prevotella bivia

Other microorganisms

- Chlamydophila pneumoniae

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- Mycoplasma genitalium

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Ureaplasma urealyticum

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

No harm has been found with use during pregnancy.[3] However, there are no adequate well-controlled studies in pregnant women.[23]

Safety of the medication during breastfeeding is unclear. It was reported that because only low levels are found in breast milk and the medication has also been used in young children, it is unlikely that breastfed infants would suffer adverse effects.[4] Nevertheless, it is recommended that the drug be used with caution during breastfeeding.[3]

Airway diseases

Azithromycin appears to be effective in the treatment of COPD through its suppression of inflammatory processes.[24] And potentially useful in asthma and sinusitis via this mechanism.[25] Azithromycin is believed to produce its effects through suppressing certain immune responses that may contribute to inflammation of the airways.[26][27]

Adverse effects

Most common adverse effects are diarrhea (5%), nausea (3%), abdominal pain (3%), and vomiting. Fewer than 1% of people stop taking the drug due to side effects. Nervousness, skin reactions, and anaphylaxis have been reported.[28] Clostridium difficile infection has been reported with use of azithromycin.[3] Azithromycin does not affect the efficacy of birth control unlike some other antibiotics such as rifampin. Hearing loss has been reported.[29]

Occasionally, people have developed cholestatic hepatitis or delirium. Accidental intravenous overdose in an infant caused severe heart block, resulting in residual encephalopathy.[30][31]

In 2013 the FDA issued a warning that azithromycin “can cause abnormal changes in the electrical activity of the heart that may lead to a potentially fatal irregular heart rhythm.” The FDA noted in the warning a 2012 study that found the drug may increase the risk of death, especially in those with heart problems, compared with those on other antibiotics such as amoxicillin or no antibiotic. The warning indicated people with preexisting conditions are at particular risk, such as those with QT interval prolongation, low blood levels of potassium or magnesium, a slower than normal heart rate, or those who use certain drugs to treat abnormal heart rhythms.[32][33][34]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Azithromycin prevents bacteria from growing by interfering with their protein synthesis. It binds to the 50S subunit of the bacterial ribosome, thus inhibiting translation of mRNA. Nucleic acid synthesis is not affected.[23]

Pharmacokinetics

Azithromycin is an acid-stable antibiotic, so it can be taken orally with no need of protection from gastric acids. It is readily absorbed, but absorption is greater on an empty stomach. Time to peak concentration (Tmax) in adults is 2.1 to 3.2 hours for oral dosage forms. Due to its high concentration in phagocytes, azithromycin is actively transported to the site of infection. During active phagocytosis, large concentrations are released. The concentration of azithromycin in the tissues can be over 50 times higher than in plasma due to ion trapping and its high lipid solubility.[citation needed] Azithromycin’s half-life allows a large single dose to be administered and yet maintain bacteriostatic levels in the infected tissue for several days.[35]

Following a single dose of 500 mg, the apparent terminal elimination half-life of azithromycin is 68 hours.[35] Biliary excretion of azithromycin, predominantly unchanged, is a major route of elimination. Over the course of a week, about 6% of the administered dose appears as unchanged drug in urine.

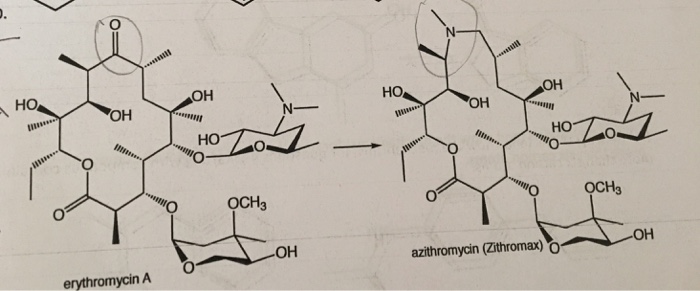

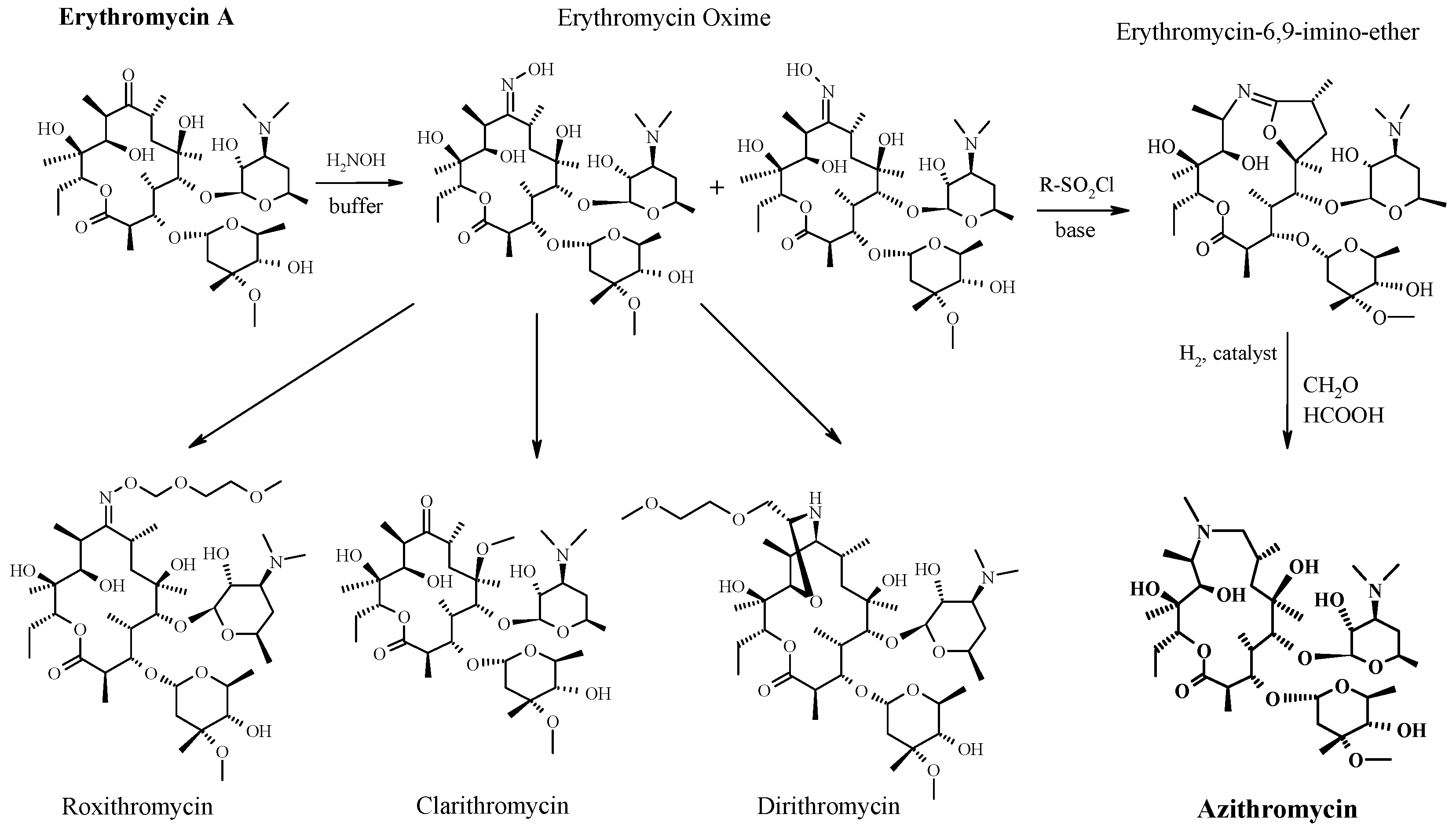

History

A team of researchers at the pharmaceutical company Pliva in Zagreb, SR Croatia, Yugoslavia, — Gabrijela Kobrehel, Gorjana Radobolja-Lazarevski, and Zrinka Tamburašev, led by Dr. Slobodan Đokić — discovered azithromycin in 1980.[6] It was patented in 1981. In 1986, Pliva and Pfizer signed a licensing agreement, which gave Pfizer exclusive rights for the sale of azithromycin in Western Europe and the United States. Pliva put its azithromycin on the market in Central and Eastern Europe under the brand name Sumamed in 1988. Pfizer launched azithromycin under Pliva’s license in other markets under the brand name Zithromax in 1991.[36] Patent protection ended in 2005.[37]

Society and culture

Zithromax (azithromycin) 250 mg tablets (CA)

Cost

It is available as a generic medication.[9] The wholesale cost is about US$0.18 to US$2.98 per dose.[10] In the United States it is about US$4 for a course of treatment as of 2018.[11] In India, it is about US$1.70 for a course of treatment.[citation needed]

Available forms

Azithromycin is commonly administered in film-coated tablet, capsule, oral suspension, intravenous injection, granules for suspension in sachet, and ophthalmic solution.[2]

Usage

In 2010, azithromycin was the most prescribed antibiotic for outpatients in the US,[38] whereas in Sweden, where outpatient antibiotic use is a third as prevalent, macrolides are only on 3% of prescriptions.[39]

READ

References

- ^ Jump up to:ab “Azithromycin Use During Pregnancy”. Drugs.com. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:abcdef “Azithromycin International Brands”. Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:abcdefghijklm “Azithromycin”. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:ab “Azithromycin use while Breastfeeding”. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Greenwood, David (2008). Antimicrobial drugs : chronicle of a twentieth century medical triumph (1. publ. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 239. ISBN9780199534845. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:ab Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 498. ISBN9783527607495.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine (6th revision ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/312266. ISBN9789241515528. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Jump up to:ab Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN9781284057560.

- ^ Jump up to:ab “Azithromycin”. International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:ab “NADAC as of 2018-05-23”. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ “The Top 300 of 2019”. clincalc.com. Retrieved 22 December2018.

- ^ Taylor SP, Sellers E, Taylor BT (2015). “Azithromycin for the Prevention of COPD Exacerbations: The Good, Bad, and Ugly”. Am. J. Med. 128 (12): 1362.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.07.032. PMID26291905.

- ^ Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG (2007). “Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 Suppl 2: S27–72. doi:10.1086/511159. PMID17278083.

- ^ Jump up to:ab “Gonococcal Infections – 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines”. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016.

- ^ Burton M, Habtamu E, Ho D, Gower EW (2015). “Interventions for trachoma trichiasis”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11 (11): CD004008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004008.pub3. PMC4661324. PMID26568232.

- ^ Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, Brook I, Ashok Kumar K, Kramper M, Orlandi RR, Palmer JN, Patel ZM, Peters A, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD (2015). “Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis”. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 152 (2 Suppl): S1–S39. doi:10.1177/0194599815572097. PMID25832968.

- ^ Hauk L (2014). “AAP releases guideline on diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children one to 18 years of age”. Am Fam Physician. 89 (8): 676–81. PMID24784128.

- ^ Neff MJ (2004). “AAP, AAFP release guideline on diagnosis and management of acute otitis media”. Am Fam Physician. 69 (11): 2713–5. PMID15202704.

- ^ Randel A (2013). “IDSA Updates Guideline for Managing Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis”. Am Fam Physician. 88 (5): 338–40. PMID24010402.

- ^ The Guardian newspaper: ‘Super-gonorrhoea’ outbreak in Leeds, 18 September 2015Archived 18 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lippincott Illustrated Reviews : Pharmacology Sixth Edition. p. 506.

- ^ Jump up to:ab “US azithromycin label”(PDF). FDA. February 2016. Archived(PDF) from the original on 23 November 2016.

- ^ Simoens, Steven; Laekeman, Gert; Decramer, Marc (May 2013). “Preventing COPD exacerbations with macrolides: A review and budget impact analysis”. Respiratory Medicine. 107 (5): 637–648. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2012.12.019. PMID23352223.

- ^ Gotfried, Mark H. (February 2004). “Macrolides for the Treatment of Chronic Sinusitis, Asthma, and COPD”. CHEST. 125 (2): 52S–61S. doi:10.1378/chest.125.2_suppl.52S. ISSN0012-3692. PMID14872001.

- ^ Zarogoulidis, P.; Papanas, N.; Kioumis, I.; Chatzaki, E.; Maltezos, E.; Zarogoulidis, K. (May 2012). “Macrolides: from in vitro anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties to clinical practice in respiratory diseases”. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 68 (5): 479–503. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1161-x. ISSN1432-1041. PMID22105373.

- ^ Steel, Helen C.; Theron, Annette J.; Cockeran, Riana; Anderson, Ronald; Feldman, Charles (2012). “Pathogen- and Host-Directed Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Macrolide Antibiotics”. Mediators of Inflammation. 2012: 584262. doi:10.1155/2012/584262. PMC3388425. PMID22778497.

- ^ Mori F, Pecorari L, Pantano S, Rossi M, Pucci N, De Martino M, Novembre E (2014). “Azithromycin anaphylaxis in children”. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 27 (1): 121–6. doi:10.1177/039463201402700116. PMID24674687.

- ^ Dart, Richard C. (2004). Medical Toxology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 23.

- ^ Tilelli, John A.; Smith, Kathleen M.; Pettignano, Robert (2006). “Life-Threatening Bradyarrhythmia After Massive Azithromycin Overdose”. Pharmacotherapy. 26 (1): 147–50. doi:10.1592/phco.2006.26.1.147. PMID16506357.

- ^ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 132–133.

- ^ Denise Grady (16 May 2012). “Popular Antibiotic May Raise Risk of Sudden Death”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Ray, Wayne A.; Murray, Katherine T.; Hall, Kathi; Arbogast, Patrick G.; Stein, C. Michael (2012). “Azithromycin and the Risk of Cardiovascular Death”. New England Journal of Medicine. 366(20): 1881–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003833. PMC3374857. PMID22591294.

- ^ “FDA Drug Safety Communication: Azithromycin (Zithromax or Zmax) and the risk of potentially fatal heart rhythms”. FDA. 12 March 2013. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:ab “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Banić Tomišić, Z. (2011). “The Story of Azithromycin”. Kemija U Industriji. 60 (12): 603–617. ISSN0022-9830. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ “Azithromycin: A world best-selling Antibiotic”. www.wipo.int. World Intellectual Property Organization. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Hicks, LA; Taylor TH, Jr; Hunkler, RJ (April 2013). “U.S. outpatient antibiotic prescribing, 2010”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (15): 1461–1462. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1212055. PMID23574140.

- ^ Hicks, LA; Taylor TH, Jr; Hunkler, RJ (September 2013). “More on U.S. outpatient antibiotic prescribing, 2010”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (12): 1175–1176. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1306863. PMID24047077.

External links

Keywords: Antibacterial (Antibiotics); Macrolides.

- “Azithromycin”. Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Zithromax, Azithrocin, others[2] |

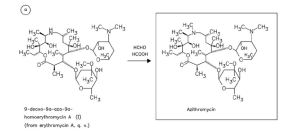

| Other names | 9-deoxy-9α-aza-9α-methyl-9α-homoerythromycin A |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697037 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

By mouth (capsule, tablet or suspension), intravenous, eye drop |

| Drug class | Macrolide antibiotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 38% for 250 mg capsules |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 11–14 h (single dose) 68 h (multiple dosing) |

| Excretion | Biliary, kidney (4.5%) |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.126.551 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

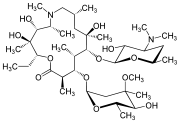

| Formula | C38H72N2O12 |

| Molar mass | 748.984 g·mol−1 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

/////////AZITHROMYCIN, Antibacterial, Antibiotics, Macrolides, CORONA VIRUS, COVID 19, アジスロマイシン ,

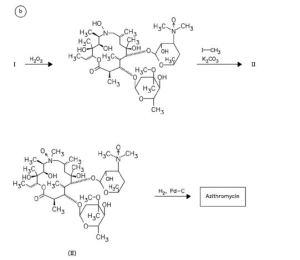

Substances Referenced in Synthesis Path

CAS-RN Formula Chemical Name CAS Index Name

76801-85-9 C37H70N2O12 2-deoxo-9a-aza-9a-homoerythromycin A 1-Oxa-6-azacyclopentadecan-15-one,

13-[(2,6-dideoxy-3-C-methyl-3-O-methyl-α-L-ribo-hexopyranosyl)oxy]-2-eth- yl-3,4,10-trihydroxy-3,5,8,10,12,14-hexamethyl-11-[[3,4,6-trideoxy-3-(dimethylamino)-β-D-xylo-hexopyranosyl]oxy]-, [2R-(2

R*,3S*,4R*,5R*,8R*,10R*,11R*,12S*,13S*,1

4R*)]-

90503-04-1 C37H70N2O14 [2R-(2R*,3S*,4R*,5R*,8R*,10R*,11R*,12S*,

13S*,14R*)]-13-[(2,6-dideoxy-3-C-methyl3-O-methyl-α-L-ribo-hexopyranosyl)

oxy]-2-ethyl-3,4,6,10-tetrahydroxy3,5,8,10,12,14-hexamethyl-13-[[3,4,6-

trideoxy-3-(dimethyloxidoamino)-

β-D-xylo-hexopyranosyl] oxy]-1-oxa-6-azacyclopentadecan-15-one

1-Oxa-6-azacyclopentadecan-15-one,

13-[(2,6-dideoxy-3-C-methyl-3-Omethyl-α-L-ribo-hexopyranosyl)

oxy]-2-ethyl-3,4,6,10-tetrahydroxy3,5,8,10,12,14-hexamethyl-13-[[3,4,6-

trideoxy-3-(dimethyloxidoamino)-β-Dxylo-hexopyranosyl]oxy]-, [2R-(2R*,3S*,4R

*,5R*,8R*,10R*,11R*,12S*,13S*,14R*)]-

90503-05-2 C38H72N2O14 [2R-(2R*,3S*,4R*,5R*,8R*,10R*,11R*,12S*,

13S*,14R*)]-13-[(2,6-dideoxy-3-C-methyl3-O-methyl-α-L-ribo-hexopyranosyl) oxy]-2-ethyl-3,4,10-trihydroxy3,5,6,8,10,12,14-heptamethyl-11-[[3,4,6-

trideoxy-3-(dimethyloxidoamino)-

β-D-xylo-hexopyranosyl]

oxy]-1-oxa-6-azacyclopentadecan-15-one

6-oxide

1-Oxa-6-azacyclopentadecan-15-one,

13-[(2,6-dideoxy-3-C-methyl-3-Omethyl-α-L-ribo-hexopyranosyl)

oxy]-2-ethyl-3,4,10-trihydroxy3,5,6,8,10,12,14-heptamethyl-11-[[3,4,6-

trideoxy-3-(dimethyloxidoamino)-βD-xylo-hexopyranosyl]oxy]-, 6-oxide,

[2R-(2R*,3S*,4R*,5R*,8R*,10R*,11R*,12S*,1

3S*,14R*)]-

50-00-0 CH2O formaldehyde Formaldehyde

74-88-4 CH3I methyl iodide Methane, iodoTrade Names

Country Trade Name Vendor Annotation

D Ultreon Pfizer

Zithromax Pfizer Pharma/Gödecke/Parke-Davis

numerous generic preparations

F Azadose Pfizer

Monodose Pfizer

Zithromax Pfizer

GB Zithromax Pfizer

I Azitrocin Bioindustria

Ribotrex Pierre Fabre

Trocozina Sigma-Tau

Zithromax Pfizer

J Zithromac Pfizer

USA Azasite InSite Vision

Zithromax Pfizer as dihydrate

Formulations cps. 100 mg, 250 mg; Gran. 10%; susp. 200 mg (as dihydrate); tabl. 250 mg References Djokic, S. et al.: J. Antibiot. (JANTAJ) 40, 1006 (1987). a DOS 3 140 449 (Pliva; appl. 12.10.1981; YU-prior. 6.3.1981). US 4 517 359 (Pliva; 14.5.1985; appl. 22.9.1981; YU-prior. 6.3.1981). b EP 101 186 (Pliva; appl. 14.7.1983; USA-prior. 19.7.1982, 15.11.1982). US 4 474 768 (Pfizer; 2.10.1984; prior. 19.7.1982, 15.11.1982). educt by ring expansion of erythromycin A oxime by Beckmann rearrangement: Djokic, S. et al.: J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 (JCPRB4) 1986, 1881-1890. Bright, G.M. et al.: J. Antibiot. (JANTAJ) 41, 1029 (1988). US 4 328 334 (Pliva; 4.5.1982; YU-prior. 2.4.1979). stable, non-hygroscopic dihydrate: EP 298 650 (Pfizer; appl. 28.6.1988). medical use for treatment of protozoal infections: US 4 963 531 (Pfizer; 16.10.1990; prior. 16.8.1988, 10.9.1987).